Soft Option or Hard Wall

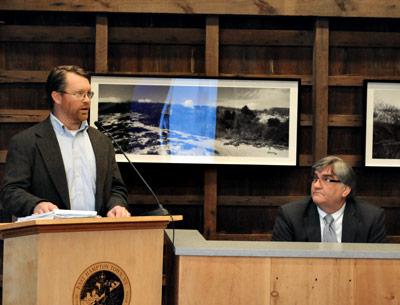

After a presentation by the Army Corps of Engineers about beach restoration in downtown Montauk, the East Hampton Town Board began to grapple this week with some of the issues involved.

The federal government would pay 100 percent of the cost, provided that the scope of the project — which could include a buried seawall or the simple addition of sand — can be agreed upon while the money is available.

Steve Couch of the Army Corps outlined several options during a packed meeting at Town Hall last Thursday. One was to buy or condemn the hamlet’s downtown shorefront hotels for relocation and construct a dune where they now stand, with a beach in front. The real estate would be purchased by the federal government, which is pursuing such a plan in areas of Fire Island.

Another option was to build a sand revetment under five feet of sand, with a 90-foot-wide beach, or to create a similar-width beach with sand alone and a 15-foot dune.

A field of five stone groins jutting into the sea was also mentioned, but for comparison only, Mr. Couch said, as the Corps no longer endorses that idea, at least not for Montauk.

Each option poses a different challenge and ongoing maintenance costs. All would be designed to withstand a so-called 75 or 100-year storm, and would provide the same protection to downtown Montauk, said Mr. Couch.

Maintenance costs, or future restoration of any project to its minimum design standards, would be covered by federal, county, and state funds, depending on their availability.

The Army Corps is expected to return within a month with a report detailing just what it will offer the town, based on a cost-benefit analysis by the agency.

“This is a fact. . . .” Supervisor Bill Wilkinson said Tuesday. “If we do not accept this money, it will be taken other places. We have a unique opportunity, and I just want to make that clear.”

State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr. urged the town board last week “to reach consensus quickly — time being of the essence.”

“These federal dollars that Congressman Bishop worked very hard to get — the attention to Montauk — could end up going elsewhere,” he said. “That point, I’m pretty certain of.” Nonetheless, he said, the decision should sit well not only with federal, state, and local officials, but also with the Montauk community.

“Montauk is in a serious state of peril, and there’s no protection there,” said County Legislator Jay Schneiderman last week.

On Tuesday, faced with pressure to be forearmed with a clear vision of Montauk’s future, town board members narrowed the options down to two: beach reconstruction with or without a buried hard structure under the sand.

Though Councilwoman Sylvia Overby expressed interest in learning more about the real estate-purchase option, the other board members seemed ready to exclude it from consideration.

“Retreat, relocate, and buy out — never going to happen,” Mr. Wilkinson said. “The Corps isn’t going to spend the money, and we don’t have the time.”

“In this particular instance, I don’t see that as an option, because I don’t think we’ll have time to get it together,” said Councilman Peter Van Scoyoc. But, he said, even should a Montauk beach be created to withstand a 100-year storm, the town must still develop “long-term strategies . . . other ways of dealing with downtown Montauk,” when considering the effects of a monster storm, larger than last year’s Category One Hurricane Sandy.

“The options are a soft option or a hard option; I think it boils down to that,” Mr. Van Scoyoc said. A rock structure under the sand “is inconsistent with coastal policy,” as delineated in the town’s state and federal-approved Local Waterfront Revitalization Program plan, he said, “and is likely to be challenged. Therefore — loss of money.”

The town, Mr. Van Scoyoc said, should urge the Army Corps to develop a project that’s “within the current coastal policies,” and has “the least potential harm.”

“I’m saying that the emergency provision may allow us to put hard structures,” said Mr. Wilkinson. “The Army Corps of Engineers is aware of the L.W.R.P.”

The town, he added, has a “very short window” to actually get federal money to pay for a beach project, “and anything that would contribute to a delay, on this board . . . would put that opportunity at risk.”

If certain standards outlined in town law are met, Kathryn Santiago, a town attorney, told the board, actions inconsistent with the L.W.R.P. could be allowed.

Mr. Van Scoyoc expressed concern that the federal agency’s analysis of which options meet its minimum cost-benefit ratio might be based on data collected right after Sandy. Since then, the beach has gained sand, the councilman pointed out, affecting reconstruction cost estimates.

The future cost to the town of maintenance or beach rebuilding, should money not be forthcoming from other levels of government, should be factored in, Councilwoman Theresa Quigley said.

Mr. Wilkinson, who had apparently already, independently, told the Corps that a buried-rock option is favored, according to Mr. Couch’s comments last week, said that “if the beach goes when they say sorry, the project’s out [of future federal, state, or county budgets], then you have rock.”

Rameshwar Das, a Springs resident and a key author of the L.W.R.P. as it was developed over more than a decade, said it would be hard to make a case that the downtown beach in Montauk is an “emergency,” and that therefore installing rocks there would require a state-approved amendment to the L.W.R.P., which could take some time. There would be no delay, he said, “if you do what is consistent with the policies of the L.W.R.P., which derive from state coastal zone management policies.”

Mr. Das also suggested the board pursue the idea, endorsed by some board members, of engaging a private coastal consultant for help weighing the Army Corps’s proposals. The Corps’s “record of coastal engineering excellence is not altogether consistent, especially on Long Island,” he said, citing a book titled “The Corps and the Shore.”

“The Corps is basically a budget-driven organization,” he said. “The bigger the project, the better they like it. They basically like building things. It’s a little like having the contractor design your house.”

Councilman Dominick Stanzione said he would endorse hiring a consultant, not only to provide information but “because the public would be more comfortable” with a decision made with help from an independent expert. But, he said, “we are against the clock in a competitive process.” He expressed concern that consulting an independent coastal expert could delay decision-making and jeopardize the chances of the project taking place in Montauk.

In his remarks last week, Mr. Schneiderman, a Montauk resident and former town supervisor, acknowledged that the town, in its Local Waterfront Revitalization Program plan, “took a strong stand” against the installation of hard structures on the ocean beach. But, he said, “Montauk is in a state of emergency. If we blow this, we have made a terrible mistake. So please, everybody come together so we can make this happen as soon as possible,” he told the board.

Wilkinson analysis