South Toward Home

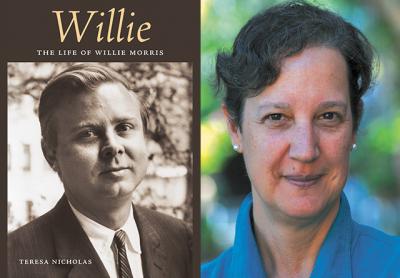

“Willie: The Life of

Willie Morris”

Teresa Nicholas

University Press of Mississippi, $20

In the summer of 1979 I was introduced to Willie Morris at Bobby Van’s, then a wood-paneled chophouse that bore no resemblance to the chic local outpost it is today. I was an aspiring writer, newly arrived in New York and on my first visit to the East End. Willie, I learned, was the self-exiled former editor of Harper’s magazine and the author of the towering memoir “North Toward Home,” hailed as “the finest evocation of an American boyhood,” in one critic’s words, “since Mark Twain.”

From that summer in Bridgehampton I remember Willie as witty, full of entertaining insights, and always disposed toward kindliness. Yet he impressed me also as a man down on his luck, old for his 44 years, and comfortable really only in the dark recesses of Bobby Van’s with friends — the writers William Styron, Joe Heller, and Irwin Shaw among them. At his round table toward the back he held court with stories of his Yazoo City youth, his dog Pete, and his bygone days in New York City.

In my cameo role, I was the on-again-off-again girlfriend of a rising Southern novelist whom Willie had befriended — the only partaker without bona fide literary credentials. Yet, he always kept a seat warm for me and took my aspirations seriously.

Later that year, according to “Willie: The Life of Willie Morris,” a splendid new biography by Teresa Nicholas, Mississippi’s favorite son would return to his beloved South, where he would tumble into a life of late-stage productivity and happiness. What a pleasure it was to read that Willie found love with JoAnne Prichard, his University of Mississippi Press editor. An output at 16 books almost tripled that of his earlier life, including “My Dog Skip,” “The Courting of Marcus Dupree,” “New York Days,” and “Faulkner’s Mississippi.” He became a colossus at U. Miss, where he reigned as writer in residence. All his life Willie would be the “Pied Piper,” one admirer wrote, adored “absolutely and blindly.”

“He drew people to him whose spirits were heightened in his company,” confided his college sweetheart and first wife, Celia Ann Buchan, “so our lives felt more charged and delicious when he was around. . . . He was outrageous in an era when outrageousness was in short supply.”

Among those Willie pulled into his orbit was Ms. Nicholas herself. As a high school student in Yazoo City, she first met Willie in the fall of 1969. “Aware of my interest in journalism,” she writes in her author’s note, “he encouraged me to get a good liberal arts education,” even stepping up to write her college recommendations. Years later she would return the favor with this book, a biography I suspect Willie would have greatly admired.

Ms. Nicholas faithfully chronicles Willie’s charmed Yazoo City youth, his controversial editorship of the student daily at the University of Texas at Austin, his Rhodes Scholar years in Oxford, and a stint at Texas Monthly, followed by the apotheosis — Harper’s, which he transformed into a “hot” publication with a new kind of journalism.

Ms. Nicholas, however, has summoned up so much more than the facts. “The Life of Willie Morris” captures the essence of the man, so rare in a biography. Sifting through letters, more than 50 interviews with friends and family, and Willie’s own words, Ms. Nicholas has cherry-picked the details that paint a lonely but gregarious man, a generous spirit, and a life that was fueled by a passion for looking back and mythologizing.

“No one at age thirty-two should write his memoirs,” maintained the economist John Kenneth Galbraith on the publication of “North Toward Home.” “Willie Morris is the only exception.” Even as he laid out the foibles of Yazoo City, his affection for his hometown stirred the hardest Yankee heart. “There was something in the very atmosphere of a small town in the Deep South, something spooked-up and romantic,” he wrote, “which did extravagant things to the imagination of its bright and resourceful boys.”

He taught his dog Skip how to carry a football and survive a tackle. He played taps on trumpet at funerals. There were the usual schoolboy high jinks in school cemeteries — like his grandfather before him, Willie never missed an opportunity to pull a prank.

Yet he took his future seriously. Though exercises in “intellection” in the Deep South were generally discouraged, young Willie surprised even himself, Ms. Nicholas reports, when he admitted to a friend that he wanted to write. As editor of the school newspaper he developed the chops as well as an ambition to “tell the truth” and to cast off “the tragic shroud of indifference.” A co-senior class president, Willie was voted “wittiest” and “most likely to succeed,” according to his 1952 yearbook entry.

Most striking in Ms. Nicholas’s retelling, young Willie evolves from a good old Delta boy — i.e., comfortable with the segregated status quo — into a man with a keen awareness of the inequities of the world at large. In “North Toward Home” Willie admitted to a “secret shame” from the age of 12. Approaching a small black boy, he “slapped him across the face, kicked him with my knee, and with a shove sent him sprawling on the concrete” for sport. But at the University of Texas, to the administration’s chagrin and ultimate censorship, he advocated social justice in the press — the ardent stance he would take for the rest of his life. The Delta boy –became a bleeding heart.

During his eight years at Harper’s, four as its editor, Willie banished “arid” editorializing and turned the publication into a “writers’ magazine.” Notably, he scored a coup by publishing an excerpt of “The Confessions of Nat Turner,” Styron’s fictional account of a slave revolt in Virginia of 1831. Gay Talese’s profile of The New York Times in Harper’s would become the best-selling “The Kingdom and the Power,” shaking the public’s perception of the media to its core. The issue featuring Norman Mailer’s “The Prisoner of Sex,” a “combative analysis” of the women’s movement, sold more than any other in the history of the magazine.

“From time to time,” writes Ms. Nicholas, “the magazine would publish an article that profoundly changed the way the nation thought about an important issue” — such was Seymour M. Hersh’s “May Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath” on Vietnam. Harper’s publisher balked at rising expenses and held the editor to the bottom line. When Willie resigned, most of his staff followed him out the door.

Remarkably, Ms. Nicholas tells Willie’s compelling story in 127 pages, setting what I wish were a new standard for biography. She never strays far from Willie’s words, which summon up place and time with specificity. “I like the way they sell chicken and pit-barbecue and fried catfish in the little stores next to the service stations,” wrote Willie of his return to the South. “I like the unflagging courtesy of the young, the way they say ‘Sir’ and ‘Ma’am.’ I like the way the white and black people banter with each other, the old graying black men whiling away their time sitting on the brick wall in front of the jailhouse. . . .”

Willie died of heart failure at 64, having never become “the novelist he’d aspired to be.” His single novel, “Taps,” which he reworked over the decades, was published with his widow’s editorial help posthumously.

But the imprint he left on nonfiction writing deserves to be celebrated anew. A place belongs most to the person who claims it the hardest and most obsessively, according to Joan Didion. “That was Willie and his Yazoo,” writes Ms. Nicholas in her inspired prose, an echo of her subject’s own, “claiming it, remembering it, wrenching it, shaping it, rendering it, and ultimately remaking it to fit the image in his prodigious memory.”

Ellen T. White is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” about the great romantic women of history. She lives in Springs.

Willie Morris lived in a house on Church Lane in Bridgehampton for seven years.