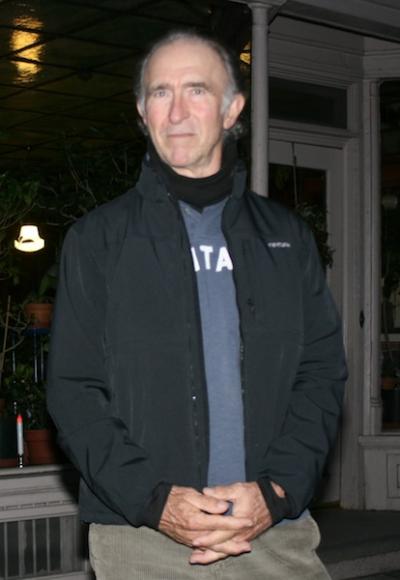

Sports Psychologist Is Fascinated by the Mind Game

“The brain, then, is a terrible thing. . . ?” this writer said after Dr. Paul Weinhold, a sports psychologist, sat down during a recent visit to The Star.

“A terrible and a wonderful thing,” he said. “The mind plays an incredible role as to how you’re going to perform. There’s no level of athlete who’s exempt, whether you’re a professional or a weekend warrior.”

“As the skill level increases,” he continued, the ante is upped, as it were. “For instance, if you look at an elite player — and I work with a lot of them, in all different sports — what separates those who succeed from those who struggle is the mind game, the mental component.”

“Jack Nicklaus was giving a seminar and he said he never missed a putt within three feet. Somebody in the audience said, ‘But Mr. Nicklaus, I once saw you miss a putt of probably two-and-a-half feet.’ ”

“ ‘No, sir,’ ” Nicklaus said. ‘I don’t remember that.’ He had chosen to forget the mistake, because he wished to remain positive. It’s a strategy that’s best for athletes to follow. You don’t want to be reminded of mistakes because the brain then becomes too captivated by the failures, and in so doing activates a lot of the sympathetic nervous system. That kind of obsessing produces a physical result. Your heart beats faster, your blood pressure rises . . . the brain has initiated what we feel as anxiety.”

When one is “in the zone,” performing at an extraordinarily high level, Weinhold said, “the mind is quiet, no negative energy is being created. Countless examples exist of victorious athletes acknowledging in interviews the overwhelming importance of an additional shift that allows a calm, determined, positive focus. Successful athletes need to master and sustain this shift. This ‘zone,’ or ‘flow’ is best described as completely focused motivation.”

In the early days of his career, Weinhold, who had played tennis at the University of Illinois “before academics got in the way,” worked largely with tennis players, including elite junior players at the Port Washington Tennis Academy, “though not in the Harry Hopman years.” Later, he came to work, he said, with professionals in golf, football, basketball, baseball, swimming, gymnastics, sailing, riding . . . even billiards.

“Billiards is very, very psychological. You’re thinking way ahead to position your shots. There are a lot of opportunities for tension to come into play. You must be completely in the moment. It’s comparable to golf because of all the time you have to think. If the brain thinks too much it goes into rapid beta activity. An alpha rhythm, a slow rhythm where your heart beats very, very consistently, is preferred. . . . When you’re not activating the sympathetic nervous system, your heart settles into a very, very comfortable rhythm, which allows you to feel less tension and helps you focus on what you’re trying to accomplish. . . . The brain is the narrator, we’re always judging ourselves, but we can, through training, release our conscious minds so that we can, if we’re golfers, say, play the ball as it lies by summoning our energy to execute the best shot we can manage.”

Lately, he has been working with the half-dozen boys and one girl who constitute the first class of the Ross School’s Tennis Academy. “We try to get together as a group every Friday. They’re very talented kids, a great group. I’m there to help them reduce the anxiety of playing what is inherently a very difficult game, to modify how the pressure of tournament play is felt. They’re between the ages of 11 and 15, so I’m getting them at the right time to introduce them to the mental side of the game. If they advance, you want their minds not to be working against them. Their bodies will be more comfortable if their minds aren’t working against them. You look at that sprinter, Usain Bolt. He’s so confident, he looks so comfortable. He breaks out of the blocks and he starts looking around. I would think that he’s done sports psychology work. He can let everything go. . . . Focus and confidence go hand in hand. If you’re confident, you will see the ball coming to you more clearly. Suddenly it becomes larger even though it’s coming at a rapid speed.”

“The best,” he went on, “are confident — in any sport. They’re not adding an enormous amount of pressure on themselves because they’ve already incorporated into themselves the knowledge that they will not always be perfect. It makes no difference whether you’re an athlete or a surgeon or a musician. I’ve worked with some top musicians — they like the idea that I come from a sports psychology background. They recognize that what they do is related. They’re entertainers too, they’re both performing very intricate maneuvers, though in different areas. They realize the mind can play havoc with their performances. They want to be focused, confident, to quiet the mind.”

The effects of a sports psychologist’s work might be somewhat hard to quantify, the interviewee said, inasmuch as “they’re measured not only in terms of winning and losing, but, for me, in how a player adapts to the game, how he maintains his resiliency and adaptability on the court. If I see a player, for instance, who has previously been angry but is no longer manifesting anger on the court, I consider what I’ve done to have been a great success.”

“I like to see an athlete who enjoys the competition, who doesn’t back away, who wants to learn from the competitive circumstances,” he continued. “I’m fascinated by how the mind impacts performance, whether it’s Tim Tebow, John Elway, or the America’s Cup sailor Dennis Conner. John Elway had the dry heaves every Sunday because of his anticipation of the game, but once he was on the stage he would just play the game as he did as a kid.”

When it came to coaching, he said, “John Wooden was one of the best psychologists who ever came along. He was very instructional, very positive, not insulting. He didn’t create negative energy and he got the most out of his players. . . . Bobby Knight had wonderful athletes who despite his behavior performed well. His players said they feared him but loved him. He would have been a much better coach had he not been that way, if his emotions hadn’t got the better of him. Of the two, I definitely prefer John Wooden.”

He said the Ross Academy boys’ results in regional tournaments were attesting to the efficacy of his work there. “It’s not about winning or losing, but about how they compose themselves emotionally. The goal is to help them understand who they are and to give them an opportunity to engage in the educational process, to use sport as a vehicle to avail them of higher educational opportunities, to help them feel composed and emotionally intelligent. Emotional intelligence, by the way, bears more strongly on success in life than intellectual intelligence. E.Q. is more important than I.Q. If you have both, you’ve got it.