Students Digest ‘Omnivore’s Dilemma’

A farmer, a fishmonger, a beekeeper, and a shellfish grower walked into an eighth-grade English class . . . and it was fun, agreed the children.

The East Hampton Middle School’s eighth-grade English language arts class was assigned the task of reading “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” by Michael Pollan, an investigative look at the politics and trends behind the food supply and consumption in today’s society.

It is not exactly scintillating material for most 14-year-olds but with a lesson in experiential learning instituted by Meredith Hasemann, an English teacher at the school, and the rest of the English department, the otherwise dry subject matter was lifted off the page.

Over the course of a month, several local food purveyors, farmers, and chefs visited the middle school to speak about the industry and, essentially, illustrate an overarching directive from the book’s author: Know thy farmer. The health-conscious theme also ties into a health and wellness thread that runs throughout the middle school.

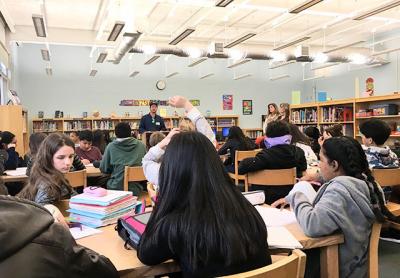

On Tuesday, a combined class of about 50 students gathered in the school library to hear from Ian Calder-Piedmonte, a partner at the popular Balsam Farms in Amagansett and East Hampton. As an introduction, Ms. Hasemann reminded the students of the book’s focus.

“The author undertakes an investigation into food and how it arrives in front of us,” said the teacher. “The book is broken into four food groups: industrial food, such as McDonald’s, industrial organic food, such as Whole Foods Market, industrial local and sustainable foods, like farm stand produce, and the hunter and gatherer D.I.Y. food chain, where the author goes out and shoots a boar for his dinner.”

Together with Ms. Hasemann, Matthew Ward and Judy Horan, the other eighth-grade English teachers, helped curate a list of guest speakers that would best illustrate each of these groups. Scott Chaskey, the director of the Peconic Land Trust’s Quail Hill Farm in Amagansett, represented the local and sustainable food group in the book. Peter Topping of the East Hampton Town Shellfish Hatchery spoke about the hunter and gatherer category and told students where to find oysters and clams for dinner. Mary Woltz, a beekeeper and manufacturer of the honey-based Bee’s Needs products, straddled the hunter-gatherer and local and sustainable groups. Charlotte Sasso, the owner of Stuart’s Seafood Shop in Amagansett, covered both the industrial organic group and the hunter-gatherer type. John Halsey, of the venerable South Fork farming family, spoke about his connection to local and sustainable agriculture.

And on Tuesday, it was Mr. Calder-Piedmonte’s turn. The students seemed genuinely engrossed by the farmer’s story of how Balsam Farms got started (he met his business partner, Alex Balsam, while studying philosophy at Cornell University). After a brief overview of their produce and practices, it was the students’ turn to ask questions. Several hands shot up.

“Do you spray vegetables with chemicals?” Only naturally-derived and organically-approved ones.

“Are you rivals of Quail Hill?” No, we’re friends, said the smiling farmer.

“Do you grow anything exotic?” The children learned that the farm will soon be offering kiwi berries, a semitropical fruit, and artichokes, mostly propagated in Mediterranean climates, two offerings made possible by the unique weather patterns of eastern Long Island.

Experiential, or hands-on, learning is a buzzword in educational circles today, the theory being that it helps students absorb information better and think more critically than they would by simply listening to a teacher speak in a classroom. It has, in fact, been around for a very long time, loosely based on Aristotle’s philosophy: “That which we learn, we only learn by doing.”

The East Hampton Middle School seems to be wholeheartedly encouraging teachers who want to take teaching outside of the classroom. “All middle school learning should be hands-on,” acknowledged Charles Soriano, the school’s principal.

Earlier this year, seventh graders in Cara Nelson’s social studies class went on a far-flung learning experience when their teacher participated in the World Marathon Challenge and ran seven marathons on seven continents in seven days. With the aid of Google Classrooms technology, Ms. Nelson connected with her students from each destination, offering the youngsters firsthand lessons about the places and topics being covered in the classroom.

For Ms. Hasemann, the goal of bringing in the speakers was to help students “make informed choices about the foods they buy.”

“If, indeed, they interview a farmer as they would a contractor or a doctor, they can make more informed choices,” she said. “I want them to know what is available here in East Hampton, that they can go clamming for their own food, or eat food grown in their neighborhood, and that they can support local food solutions.”

Having heard from local food sources, the next task for her charges is to complete a project, displaying a proficiency of the subject matter. After reading about the slaughterhouse in the book, some children, said Ms. Hasemann, will choose to be vegetarian or vegan for a week. Some will compare the food chain in Ecuador, or their grandparents’ home in Ireland, to the foods they eat in America. Some grow seeds. Others go fishing or clamming, and some prepare a healthy meal for their family.

“In some way, each student will investigate the food chain and write a seven-page paper on it,” said the teacher.

Two years ago, she said, this final project led one student to compare a McDonald’s sandwich with another from the East Hampton Middle School cafeteria, and an organic, breaded chicken sandwich from Harbor Market in Sag Harbor. The experiment found that the school’s sandwich withstood mold and decay the longest, leading the student to conclude that it contained the most additives of the three. As a result, the school has changed much of the food it serves its students.