A Surfing Life

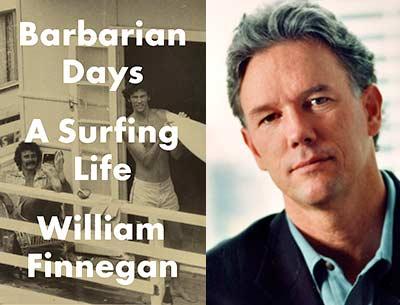

“Barbarian Days”

William Finnegan

Penguin Press, $27.95

With notable exceptions, most surf writing and storytelling has appealed exclusively to surfers. The sometimes kitschy insider stuff, the you-wish-you-here-but-you’re-not magazine articles, even the iconic “Endless Summer,” most of it is of limited interest beyond the growing tribe. Few have successfully transmitted to a broader audience the sport’s intangible appeal.

Sometimes that’s intentional; understanding the language, and the surf world itself, is a tribal sign of belonging.

That all changed, at least for me, in the mid-’90s when a package arrived from a surfing friend. We’d succumbed together to the sport’s pull, dropped everything, and chased waves for years. “This guy gets it,” said the note with the two New Yorker magazines.

William Finnegan’s two-part New Yorker series, “Playing Doc’s Games,” on the emerging San Francisco surf scene and one of its central figures, an antic hippie oncologist called Mark Renneker, unraveled the inexplicable obsession and the magic of the sport.

There it was, pulled together by a keenly observant reporter: the characters, the unwritten rules, the beauty, the fear, the humiliation, the brazen egos, the pull of it. It was sparing, without sentimentality, told with a crystal clear storyteller’s voice.

Like surfing, with its way of letting you go and pulling you back, Mr. Finnegan the surfer has now returned with a memoir that again breaks new ground for surfing literature. “Barbarian Days,” published this summer, is his account of living with that “wily mistress,” surfing. It is also the story of a coming of age of a man and a sport. Both grew up over the last 50 years, and, in both cases, for good and ill. Mr. Finnegan allowed his other ambition, to be a writer and journalist, to fill up his life, and then fell in love and had a family. He fits surfing into the margins of a busy life now. And surfing itself, well, it has grown up into something commercial and popular, unrecognizable to anyone who taught himself and surfed alone in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s.

The topic itself would be a local hook enough, seeing that so many people on the South Fork call themselves surfers, and to all of us this should be required reading. But Mr. Finnegan is no stranger to these waters. A sometimes reluctant longboarder at Ditch (it’s in the book), he hunts for waves around here with his friend Peter Spacek, the illustrator, cartoonist, and artist. Mr. Finnegan’s escapades with Mr. Spacek on the island of Madeira are central to the final chapters of his memoir. There, married, pushing middle age, with a noted career in the world beyond, Mr. Finnegan lunges into massive, terrifying surf and asks himself, Why? Why do I do this crazy thing?

And the answer — like the surf sirens who won’t let him go — wells up, almost effortlessly. “A set rolled through, shinning and roaring in the low winter afternoon sun, and my throat clogged with emotion — some nameless mess of joy, fear, love, lust, gratitude.”

As it happened, The New Yorker series in the 1990s was an anomaly for Mr. Finnegan. After dropping out to chase waves in his late 20s, he returned to the United States to become a journalist who focused on Africa, on international conflict, on the illegal drug trade, and on poverty, here and abroad. He’d been hired by The New Yorker as a staff writer in 1987.

But, really, deep down, he was always a surfer. And that psychic wrestling between the passion that consumes him — the search for just one more single, perfect day; some would call it an adolescent, egotistical obsession — and everything else that matters in life is the story of “Barbarian Days.” Wrestling hard with that, it took him seven years to write “Playing Doc’s Games,” delayed by war coverage, reporting from ravaged places, relationships, moves across the country — all those other “more important matters.” And it took some 30 years for him to produce “Barbarian Days.” Thankfully, as Mr. Finnegan himself would say, “surfing, ever wily, twisted free.”

Mr. Finnegan was 26, disenchanted with predictable, materialistic American life, when he and his childhood friend Bryan Di Salvatore took off for the South Pacific with their surfboards, no fixed plans to return, and their notebooks (both were working nonwriting jobs at the time, but they believed themselves to be writers). They had enough money to carry them for months, maybe longer. The trip lasted four years and included the discovery of what is now one of the most famous waves on the planet on the Fijian island of Tavarua.

Viewed from 2015, with surf lessons running at $100 or more an hour at beaches around the world, seemingly everyone calling himself a “surfer” — you’ve heard it: “I learned at a surf camp in Costa Rica” — and surf vacation packages advertised in The New York Times, surfing can now seem almost as conventional as golf.

But in the ’60s and ’70s, when surfing was taking hold of Mr. Finnegan, the sport was nascent, unconventional, gritty, and, most important, countercultural. Mr. Finnegan’s journey was before Google Earth had mapped out almost every coastline. He had no certain destinations, just maps, a sense of the possible, and optimism. His aim was to find perfect waves — and he did — but as it turned out he was searching for something else entirely, something that only came clear at the end of his journey, when he returned to the States.

“Barbarian Days” is a tale of personal self-discovery. Mr. Finnegan admits to his own selfish sexism. His girlfriends join him on his adventure only to discover that he has only one mistress, surfing, and their ambitions and lives are secondary to his. He recognizes his white privilege on his travels through poor South Pacific islands. With barely enough money to get by, he and Mr. Di Salvatore occasionally depend on the generosity of locals who extend food and shelter to these two boys from America, who have the luxury to loaf around finding themselves and playing in the ocean.

It is Mr. Finnegan’s honesty, immense curiosity, and almost anthropological powers of observation about the world, about friendship, and about the difficult choices in life that make his story compelling and his voice so appealing. But it’s his tumultuous relationship to surfing — surfing’s hold on him — that separates this memoir from so many others. When he is caught outside at a break in Madeira, with night falling and the waves going from huge to giant, you are rapt, searching with him for the hope of lights on the seawall that seems so far away, and a way back to life on land, and the safety and predictability of all that.

Biddle Duke, an editor and publisher of weekly newspapers in Vermont, lives part time in Springs.