Surgery (With Complications)

“The Way of the Knife”

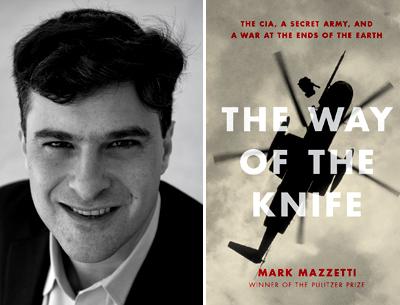

Mark Mazzetti

Penguin, $29.95

No matter what political policies you embrace, “The Way of the Knife” is a lively, engaging, factual account of our real war against terrorism — and another real war between the Central Intelligence Agency and the Pentagon.

Mark Mazzetti, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and national security correspondent for The New York Times, has given us a vivid portrait and history of the transformation of “a traditional espionage service” into “a killing machine, an organization consumed with man hunting.”

The United Nations Committee Against Torture prohibits “cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment,” yet the Bush-era detention-and-interrogation and outsourcing programs were infamously divisive and morally outrageous strategies that eventually backfired. Forced confessions didn’t work — and the U.S. lost the moral high ground.

Ironically, President Obama’s apparently ethical pledge to close Guantanamo and to terminate morally abhorrent practices has led us to “killing by remote control . . . the antithesis of the dirty, intimate work of interrogation,” as Mr. Mazzetti tells us. Many Republicans and Democrats favored this surgical approach as a (virtually) “clean” and (relatively) “risk free” way to deal with terrorists. Surgery, however, co-exists with complications.

In a review and summary of 12 recent public opinion polls, Micah Zenko (Council on Foreign Relations, March 18) reported that averaged together these polls “demonstrate that 65 percent of Americans support targeted killing of suspected terrorists, and 51 percent approve killing of U.S. citizens suspected of terrorism.” Time magazine ran a story on the same day about drone management subcontracts and degree-granting institutions with this headline: “Majoring in Drones: Higher Ed Embraces Unmanned Aircraft.”

Suicide bombings and religious fanaticism are intrinsically asymmetrical and unfair. “They” attack us with explosives hidden in body cavities and their underwear, using box cutters, pressure cookers, airplanes, and truck and car bombs via scores of public vulnerabilities. As seemingly helpless victims, we initially had a very limited repertoire and puzzling range of responses. Mourning and moral outrage left some of us feeling weak, defenseless, and perhaps even pathetic following 9/11. What was a “leader of the free world” to do? Take the moral high ground? Strike back? Both? How?

While deploring the torture programs, Mr. Obama chose targeted killings. The internal maneuvering, public posturing, private debates on the pros and cons, and complications make up a large part of Mr. Mazzetti’s richly detailed, evidence-based, and well-documented story of drone warfare.

In 2003, for example, the White House was planning to commemorate a U.N.-sponsored event dedicated to the support of torture victims by releasing statements like these: The U.S. is “committed to the worldwide elimination of torture” and is “leading the world by example.” (Complication: We weren’t.) George W. Bush had authorized the C.I.A. to engage in what was widely believed to be torture, and these nonsensical platitudes were nixed by the agency before their release out of concern that its officers might be “vulnerable to legal action in the U.S. or abroad.” This was the beginning of the end of the C.I.A.’s “deniable” torture program.

Enter Blackwater, with its “unilateral, unattributable capability” for terrorist assassinations that would nominally be under C.I.A. control. Once given specific missions, Blackwater had wide autonomy. Much of its involvement with the C.I.A. remains a tightly held government secret. But one former C.I.A. agent in retirement is quoted by Mr. Mazzetti as wondering why the U.S. would make a distinction between killing people from a distance using an armed drone versus training humans to do the face-to-face killing themselves: “How we apply lethal force, and where we apply lethal force — that’s a huge debate that we really haven’t had.”

Every complaint against the C.I.A.’s torture programs pushed its leaders to a deadly — and perhaps inevitable but uncomplicated — conclusion: “The agency would be far better off killing, rather than jailing, terror suspects.” This was despite the Detainee Treatment Act passed by Congress in 2005 banning “cruel, inhuman, and degrading” treatment of any prisoner in American custody. Was this “in for a penny, in for a pound”? Would our government speak with a forked tongue? Or was this merely another complication?

Mr. Mazzetti relates how the C.I.A. was concerned that its agents might be prosecuted for their interrogation efforts, especially after the Detainee Treatment Act was passed. The C.I.A. is a paranoid institution (just because you’re paranoid does not mean nobody’s following you). Its director at the time, Porter Goss, then told the White House he would shut down all interrogations. The White House sent Andrew Card, Mr. Bush’s chief of staff, to calm the C.I.A.’s concerns. Mr. Card, who tried to make a joke out of presidential pardons, was unsuccessful in allaying C.I.A. fears of prosecution but suggested that C.I.A. officers might receive presidential pardons after any convictions. The C.I.A. officers were not amused.

If the interservice rivalries within the U.S. government did indeed amount to a real war, as they sometimes did, Donald Rumsfeld saw a weakened C.I.A. as an opportunity to expand the reach of the Pentagon onto C.I.A. turf — to kill, capture, and spy in more than a dozen countries. The Defense Department’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) had a budget of about $8 billion in 2007 for secret operations and for running their own wars.

The boundaries between Langley and the Pentagon faded as C.I.A. spies fought like soldiers, and Defense Department Navy Seals and Delta Force operatives engaged in clandestine activities, e.g., finding and slaying Osama bin Laden. The C.I.A. and JSOC did collaborate. Real real wars were taking place in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

Passages in Mr. Mazzetti’s account read like a complex John le Carre spy novel. U-Turn Media, a small Czech firm that streamed video porn to mobile phones, had a weird program called Czech My Tits. The only people who had the money to pay for the technology were in the porn industry and in the intelligence community. U-Turn engaged in psychological warfare, or “psy-ops,” by creating video games to engage Muslims who disliked the U.S. to influence their perceptions of the U.S. and simultaneously collect information and intelligence about who was viewing these games — a triple-play: “The spies wouldn’t have to go hunting for information; it would come to them.”

For example, Iraqi Hero was one game that allowed a player to shoot up terrorist insurgents who were killing civilians in the streets of Baghdad; the goal was to reach an Iraqi police station and deliver plans of an upcoming terrorist attack.

Many colorful personalities profiled in “The Way of the Knife” come to life because Mr. Mazzetti portrays them vividly. Dewey Clarridge, a retired C.I.A. officer, was a freelance operative running his own “shadow C.I.A.” Abdullah al-Asiri was an anti-Saudi who tried to kill Prince Muhammad bin Nayef by offering to surrender and then exploding his rectum-implanted bomb prematurely, which blew him apart but left the prince with minor wounds only. Michele Ballarin, a wealthy heiress and concert pianist, was hired by the Pentagon to gather intelligence about militants in Somalia.

There are plenty of complex moral (and even Talmudic) questions posed in this fine book, including “What are the new rules of warfare against terrorism?” Collateral damage, complications, and risk accompany all surgical interventions and drone strikes.

Mark Mazzetti will be signing copies of “The Way of the Knife” at the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night fund-raiser on Aug. 10 and serving as guest of honor at one of its dinners.

Stephen Rosen, a physicist, was a member of the senior professional staff at a prominent think tank engaged in classified military research and defense policy. He lives in New York and East Hampton.