Survivors

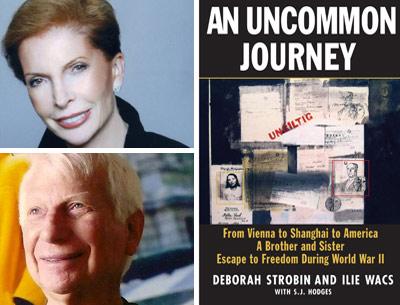

“An Uncommon

Journey”

Deborah Strobin and Ilie Wacs

Barricade Books, $24.95

Just as many people believe that the name of every victim of the Holocaust deserves to be remembered in perpetuity, so, too, it is held, the story of each survivor deserves to be told and heard. Both gestures are rooted in the dual needs to honor and to remember.

Deborah Strobin and Ilie Wacs, in their joint memoir, “An Uncommon Journey: From Vienna to Shanghai to America — A Brother and Sister Escape to Freedom During World War II,” shed light on a story of survivorship less often told but nevertheless worthy of being heard.

Between 1937 and 1941, approximately 20,000 European Jews fled to Shanghai, China, seeking refuge from the ever-tightening noose of Nazi oppression. The Wacs family, residents of Vienna, was among them — Moritz, a skilled tailor, Helen, a shy housewife and mother, and their two children, Ilie and Dorit. In August 1939, heeding the stern warning of one of Moritz’s gentile employees (who seemed to know that war would begin on Sept. 1), the family boarded the last ship to leave Vienna for Shanghai before the Anschluss.

Part of this book’s uniqueness is its format. While the overall story is told chronologically — from childhood in Vienna, which Dorit (Deborah) is too young to remember firsthand, to competent adulthood in the United States — the narration alternates between sections headed “Brother” and those headed “Sister.” They often cover the same material, though from different viewpoints, which adds nuance. Each contributor has a distinctive voice. That those voices are quite different is jarring at first, but, ultimately, it leads to a clear understanding of precisely who each of the authors is.

For Ashkenazi Jews from central Europe, settling into life in Shanghai was by no means easy. In addition to the obvious differences of language, culture, and climate, there were also the issues of poverty and the hardship of war that had to be faced daily. Soon after the Wacs family’s arrival, the Japanese occupied Shanghai. Along with a number of other people, Jews were forced to relocate within a one-square-mile area of the Hongkou district that was designated as the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees. In other words, a ghetto.

Interestingly, the Japanese occupiers remained unresponsive to pressure from their German allies when it came to sending the Shanghai Jews back to Europe. Mr. Wacs writes that one reason for this may have been that, during the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, the only money Japan was able to raise in Europe was from Jewish sources.

Although life in the Shanghai ghetto may not have been so harrowing as in the Warsaw ghetto or others, it was nevertheless grim. The Wacs family occupied an apartment of one and a half rooms, with a communal toilet outside. Even boiled water had to be purchased daily. For cooking, a large flowerpot was turned into a makeshift hibachi.

Eventual liberation came in 1945. Mr. Wacs writes: “Then on July 17, 1945, I will never forget the date, American bombers made their usual noon appearance, high in the sky. Only this time, instead of flying over, they opened their cargo doors, and bombs fell like rain. Until that moment, despite all our hardships, I had considered myself a spectator of the war, staring out my window, drawing the life below. As the ground shook and Mutti screamed for me to ‘Run!’ it occurred to me that I might not be around to see what happened next.”

His sister, Ms. Strobin, eight years younger, has the following recollection of the same event: “We heard the planes before we saw them, and I could tell they were American planes. American planes were like a bullet, buzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz, while Japanese planes were squeaky and clunky sounding. Mutti yelled at both of us, ‘Get downstairs!’ but Ilie wouldn’t budge, he wasn’t finished with his drawing. . . . He was trying to capture the moment in charcoal. . . . As the bombs began to land, he kept drawing.”

Relief from war’s end was short-lived. It wasn’t long before the Chinese Communists began their takeover of the mainland. According to Ms. Strobin, “Once again, we were on the last ship out. Last boat out of Vienna, because of Papa’s stubbornness, and, for the same reason, we were among the last people to leave Shanghai.”

The remainder of the book is an account of what happened to the authors and their parents in the many years that followed. It is an intimate, sometimes poignant, look at a family that kept going, out of affection and loyalty to one another and despite the cruel vagaries of history.

A worthwhile subtext is how both of the authors came into their own. Mr. Wacs had an easier time of it. His talent as an artist was discovered while the family was in Shanghai. Through the intervention of a sympathetic member of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, young Ilie was sent to art school in Paris. This led to a successful career in the fashion world — in Paris and as a well-known designer of fine ladies’ coats in the U.S. Eventually, he retired from business to devote himself to producing art. His family’s experience as stateless Jews who fled for their lives has had a significant effect upon his work, which has been exhibited, among other places, here on the South Fork.

For Ms. Strobin, the road to self-discovery and fulfillment was less direct and took longer. Over time, however, she morphed from a shy, insecure refugee girl into a confident and accomplished woman who has written a record of significant achievement as a fund-raiser, most notably in the area of stem cell research.

Two aspects of the book require comment. The first is the question of proportion, always a difficult thing to achieve. The authors’ wartime experiences and reflections occupy well less than half of the volume. Inasmuch as this part of their story holds the most potential for the greatest interest, one wishes it had been longer. Also, the book could have used a better proofreader; there are a number of missing words and small grammatical errors that should not appear in any published work.

These concerns notwithstanding, however, the authors’ stories stand on their own and speak for themselves. Papa and Mutti would be justifiably proud of their progeny.

Ilie Wacs lives in Sagaponack.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.