Tagging Great White Sharks for Research

As videotaped footage began playing of Greg Metzger battling a juvenile great white shark he had just hooked near Jones Beach using just the fishing rod and reel he was gripping, it was easy to momentarily forget the scientific nature of the project Mr. Metzger and the South Fork Natural History Museum are engaged in, and marvel at the spectacle.

The shark’s teeth were bared and its gills were flaring; its tail thrashed around as it raised its head out of the water toward the boat Mr. Metzger was on, and then tried to shake free.

Mr. Metzger’s rod was bent into a large quivering ‘C’ as he moved back and forth along the boat’s side rail, occasionally fighting to keep his footing as he tried to pull the shark in. Even if it was just a juvenile — great whites are four feet long at birth — it was only natural to wonder how Mr. Metzger avoided getting pulled into the water himself as he waited for the shark to tire out so his crewmates could lasso its tail, do a scientific workup, and tag its dorsal fin before releasing it.

It’s a drill Mr. Metzger and fellow researchers have now successfully repeated 23 times to help SoFo’s three-year-old shark research and education project get the data used to establish that Long Island’s waters are the only confirmed nursery for great white sharks in the North Atlantic.

“The number-one question I always get asked is, ‘Don’t you need a bigger boat?’ ” Mr. Metzger said with a laugh, knowing it’s a repeated line in the movie “Jaws,” not just a reasonable question about the modest 21-foot Parker boat he uses to catch and tag juvenile great white and thresher sharks from Manhattan to Montauk.

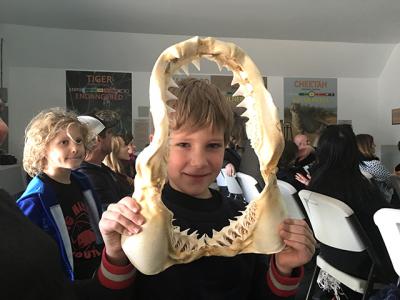

“But one of the things we want to do is get ahead of the ‘Jaws’ craze and educate people about how fantastic it is to have these sharks in Long Island’s waters, and how it fits into the bigger ecological picture,” he said.

Mr. Metzger described the program’s 2018 season for a near-capacity audience Saturday at the SoFo Museum in Southampton. He is a marine science and aquaculture teacher at Southampton High School and the field coordinator for SoFo’s shark research and education program. The program’s other principals include Frank Quevedo, SoFo’s executive director, Dr. Tobey Curtis, the SoFo program’s lead scientist, and Chris Paparo, a photographer and writer who has been documenting the group’s work and manages the Marine Science Center at Stony Brook Southampton College. Other researchers and students collaborate as well.

Last year, Mr. Curtis, Mr. Metzger, and six colleagues published a peer-reviewed article about their research for the first time in the prominent science journal Nature.

Mr. Metzger knows many people are either highly fascinated or slightly nervous to learn that sharks of all sizes, but especially great whites, summer in the Atlantic off Long Island in large numbers, along with threshers, makos, and tiger and sand sharks.

But experts agree surfers and swimmers have little reason to fear, especially if they use common sense. The risk is never zero, and you certainly don’t want to go near a school of bunker or even seals, food sources for sharks, Mr. Metzger said, noting that in the 100-plus years shark attacks on humans have been tracked in New York State, only 12 “negative interactions” have been confirmed.

“So, the chances are absolutely minuscule that you will have a negative encounter with a shark,” Mr. Metzger said.

Still, observers have a sense — accurate or not — that shark activity is increasing, perhaps because of climate change, or perhaps because great white sharks’ numbers seem to be rising since they became a protected species in federal waters in 1997 and state waters in 2005. A revitalized seal population could also be drawing sharks closer to shore.

Last summer, two children were bitten and slightly injured on separate Fire Island beaches on the same day, but officials never confirmed whether sharks were responsible or a large fish. Farther north, a man was killed by a shark off Cape Cod, raising further alarm, although it was the first fatal shark attack in Massachusetts in eight decades.

Mr. Metzger said sharks usually arrive on the southern shore of Long Island as early as May and typically head south by October toward the warmer waters of the Carolinas and Florida. Then the cycle repeats itself.

Mr. Metzger and his fishing cohorts use two types of tags on juvenile sharks. The most common is a satellite “pop-off” tag that collects data for 28 days. The second is a $12,000 CATS (Customized Animal Track Solutions) camera that Mr. Metzger and, more recently, Jeff Neubauer, a teacher at the Bridgehampton School, got funded to use for the SoFo program. Both types of tags are attached to a shark’s dorsal fin.

“The CATS cam is the most sophisticated tag you can put on an animal,” Mr. Metzger said. He explained that it provides information such as the temperature and depth of the water, the angle and acceleration when an animal changes direction, and where it travels. “Plus,” he said, it has a high definition camera, so we can literally see what the animal sees. It’s like you’re strapped on its back.”

When Mr. Metzger cued up another video — this one underwater footage of a shark biting his rope and making off with his chum bucket — the audience seemed rapt.

“All you have to do is say great white sharks,” Mr. Quevedo said afterward, “and people are fascinated. They want to know more.”