Take a Date To ‘Frankie and Johnny’

Sitting on the stage Saturday night at the Bridgehampton Community House outside the beautifully rendered set by Peter-Tolin Baker, I was taken back to the New York theater world of the 1970s and the 1980s.

At a point in time when the city itself was dying, the theater world was thriving. As businesses abandoned the city, theater groups were moving into the spaces they had left behind.

The “black box” concept was an important tool for theatrical artists. Take a few gallons of black paint and cover the crumbling plaster walls and sagging floors in a vacant office space, hang a couple of pipes across the ceiling for lights, and, voila, you had a theater.

The experience for both actors and audience was personal and intimate. It was fertile ground for experimentation and produced countless creative works, including “Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune” by Terrence McNally, which is running at the Bridgehampton Community House through Oct. 26.

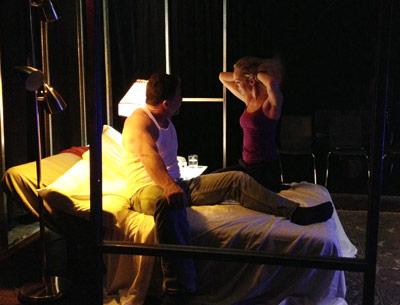

Sitting in the black box, just a few feet from the performance space, the audience finds itself inside a 1980s one-room studio apartment. Normally, a play begins when the lights come up, but “Frankie and Johnny” begins in the dark, in Frankie’s apartment, during the final moments of coital ecstasy. Frankie (Rachel Feldman) is a waitress at the restaurant where Johnny (Seth Hendricks) is a short-order cook. It is their first time ever in bed, with a clearly happy result for both.

Love-making over, the couple catch their breath, and the lights go on.

“God, I wish I still smoked,” Frankie says about lighting up after making love. “It used to be so much fun.”

The two talk about actors and movies and looking out the window into other couples’ bedrooms. The sex may have been good, but it is the post-coital experience that is the problem. Johnny is sure he has met the love of his life. Frankie? Not so sure. She is in turns annoyed, turned off, and freaked out by the ardent Johnny, who keeps pressing the pursuit.

“This is worse than ‘Looking for Mr. Goodbar,’ ” she complains, perfectly capturing her mood and the time period.

This theater company is called Hamptons International Theater Festival/The Naked Stage. Finally, the Naked Stage is doing a play where people can actually get naked. But this production passes on that score, though it strives for realism everywhere else.

These are two very challenging roles, which the actors handle well. Having said that, I did feel there were a couple of moments where they were in the lines, not in the moment, which a play like this so requires.

Sanford Meisner does not have the fame or celebrity status of Stella Adler or Lee Strasberg, yet was as influential on contemporary theater as either of them. All three were members of Group Theater in New York in the 1930s. All three became acting teachers with their own schools. All three sought truthful acting onstage, with each taking a different path to get there.

Meisner stressed the importance of truthful physical action, with a degree of difficulty. If, for example, after making love, a character makes the bed, then really make the bed. What does the bottom sheet look like after making love? Perhaps the love-making was so active that it came off. Better replace it. Focusing on a real physical action with a degree of difficulty frees the actor from the lines, which will then flow.

Similarly, when a short-order cook chops peppers, he really chops them. One of the great bits in “Frankie and Johnny” is the omelette made onstage. (Don’t go to this production hungry!) Mr. Hendricks is a bit done in by the tiny chopping board he is provided. I know the space is cramped, but give the poor guy a little more room to chop those peppers.

None of this should be taken as a knock on two very good actors. That I am ruminating on Sanford Meisner at all is a sign of how valuable this production is. The producers, Joshua Perl, who is also the director, and Peter Zablotsky, have an obvious love for raw theater, and it shows.

This is a great date show. Instead of going to the movies this weekend, plunk down $20 per ticket (Thursdays through Sundays at 8 p.m., Saturday matinee at 2), and step through the front door into the black box.