Taming a Den of Thieves

“Dodge City”

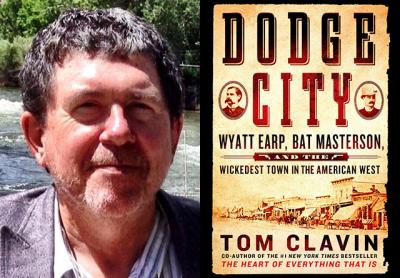

Tom Clavin

St. Martin’s, $29.99

For such a small town, Dodge City had an outsized reputation. The cow town sat in southwest Kansas, the last stop before the Great American Desert, the huge swath of mostly unexplored land that stretched to the Rocky Mountains. On the edge of the frontier, it was known as the “wickedest town in the West.”

Cowboys driving their cattle north from Texas took a pit stop in Dodge City, where the 16 saloons and 47 prostitutes could quickly lighten their wallets and get them into lots of trouble. Gamblers, bandits, and other outlaws were also there to greet them. A transitory spot filled mostly with young men drunk on alcohol and heavily armed, Dodge City was a tinderbox in search of a match. Nearly every night, the town exploded in whiskey-fueled gunfights.

This “den of thieves and cut throats,” as one Kansas newspaper described it at its highpoint — or low point, depending on whom you asked — in the late 1870s, is the subject of Tom Clavin’s new book, “Dodge City: Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and the Wickedest Town in the American West.” Mr. Clavin, a journalist and author of several well-regarded books, is an expert guide to the lawless place, but the book’s real contribution is how Mr. Clavin cuts through the myths and mystique that have accumulated around the town’s two most famous names in order to tell a more accurate history of Earp and Masterson.

It’s a daring proposition, not only because the fantasies and fictions Americans have crafted about the Western frontier are so firmly lodged in our national psyche, but also because stripping Earp and Masterson’s story of its embellishments might yield a tale not worth reading. The two lawmen, after all, had been active participants in the mythmaking of their biographies, so perhaps even they understood that their lives needed some narrative spicing up to become a story that lasted.

But, as so often is the case, Mr. Clavin shows that the truth is more compelling than fiction. In his author’s note, he writes that his book is “an attempt to spin a yarn as entertaining as tales that have been told before but one that is based on the most reliable research.” On this ground, he largely succeeds.

Before they became partners taming the streets of Dodge City, Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson had met during a buffalo hunt on the prairie. Masterson was quickly impressed by the serious and taciturn Earp, who was five years his senior. He decided to model himself on his new friend, a decision that profited him well in their new life in law enforcement.

As lawmen, they made a striking pair. Wyatt Earp was tall and slender, with piercing blue eyes and a fair complexion; Bat Masterson had darker hair, a stockier build, and stood a few inches shorter. Both men were all muscle. But it was their close friendship and commitment to each other that best characterized their partnership.

Neither man had planned for a life in law enforcement, but they took their responsibility seriously once in the role. Wyatt Earp’s leadership had significant consequences not just for Dodge City, but also for how justice was administered across the emerging Western frontier. Earp recognized that his small team faced difficult odds against the hundreds of armed and rowdy men who prowled Dodge City’s streets.

Because of this he gave his team three rules to help maintain their control and de-escalate the violence that had so easily gotten out of hand under previous lawmen’s watch. First, they were to attempt to reason gently with a man, a tactic that had surprising success in cooling off a hotheaded cowboy before he turned violent. Second, if a law officer had to shoot, he should do it carefully and with precision because so often the first man to fire did not hit his target. (Mr. Clavin’s story is filled with innocent bystanders who were killed by stray bullets shot by careless gunmen brandishing unreliable firearms.)

Third, if shooting at a man, the officer’s goal should always be to wound him rather than kill. While Earp and Masterson were both sharpshooters known for their fast draws, they actually preferred using the other end of their guns in a technique called “buffaloing,” in which they would knock a man out by striking the handle of a gun on his head.

Such practices brought a measure of peace to Dodge City and earned Earp and Masterson fame and respect across the West. But they also tamp down some of the excitement one might expect in a story about justice in the Wild West, since Mr. Clavin’s truer retelling has a lot less violence than legend had invented. Still, the book’s cast of characters, including big names like Doc Holliday, Billy the Kid, Wild Bill Hickok, and Fred and Jesse James, but also lesser-known personalities like Prairie Dog Dave and Hurricane Bill, along with Mr. Clavin’s great narrative talents, keep this a page-turning book.

One of its most notable accomplishments comes from elevating Bat Masterson to stand alongside Wyatt Earp in importance, a significant correction to the long narrative tradition in which Masterson has played second fiddle. As the author shows, Masterson’s “life was as adventurous as Wyatt’s . . . but Bat did not have a gunfight in Tombstone to burnish his legend to an iconic glow,” as Earp did. In Mr. Clavin’s telling, Masterson feels as vital to the history of Dodge City as Earp, if not also the more compelling and complicated man.

Carved on Masterson’s gravestone in the Bronx — he had finished his life working as a newspaperman in New York — were the simple words “Loved by Everyone.” That probably wasn’t true for the outlaws who found themselves face to face with Masterson. But it also may have been the truest legend ever to come out of Dodge City.

Neil J. Young is the author of “We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics.” He lives in East Hampton.

Tom Clavin will take part in the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night on Aug. 12. He lives in Sag Harbor.