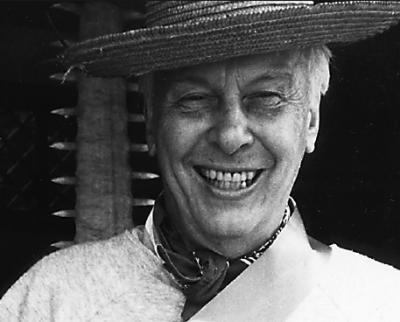

Ted Dragon, Dancer and Heir to the Creeks, Dead at 90

On Memorial Day weekend in 1992, perhaps the largest yard sale ever held in East Hampton took place at the Creeks, the 57-acre estate on Georgica Pond now owned by Ronald Perelman.

Ted Dragon, who had inherited the place upon the death of his companion of 42 years, Alfonso Ossorio, was selling most of its contents before moving out. Along with everyday dishes, unopened cans of paint, and worn-out farm tools, there was a human skeleton, lanterns from Venice’s Grand Canal, Waterford crystal goblets and chandeliers, antique garden statuary, six-foot-long elephant tusks, silk Oriental rugs, a Chinese opium-bed, a dried shark, and much, much more. Mr. Dragon, who died on Sunday, assigned the proceeds of the sale to the East Hampton Historical Society.

That he should ever have found himself sole owner of a fabled property with a theater where Enrico Caruso, Isadora Duncan, and Anna Pavlova had performed was improbable in the extreme. He was born on April 24, 1921, in Northampton, Mass., to Raymond Louis Young and Carena Dragon Young, who was French-Catholic; her family name may originally have been Dragone. His father was a restaurateur, an occupation that did not appeal to his son, who studied the piano from an early age and aspired for a time to a career as a concert pianist. As a teenager, however, he took up the ballet, eventually moving to a cold-water flat in New York City to escape his disapproving family and make a career. He was wiry but strong. He could catch girls flying through the air, and male dancers were much in demand.

One of his earliest appearances was on Broadway, as a chorus boy in the 1941 production of “One Touch of Venus,” choreographed by Agnes de Mille. But the ballet was his goal, which he achieved before long. He danced with the Paris Opera and the New York City Ballet until the fateful summer of 1948, when Mr. Ossorio, an artist, collector, and heir to a Philippine sugar fortune, spotted him at the Tanglewood Music Festival in Massachusetts.

The next year they took a place on Macdougal Alley in Greenwich Village. Mr. Ossorio bought a Jackson Pollock painting that summer, the first of many. Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner, who was to become close friends with Mr. Dragon, introduced the two men to East Hampton soon after. Three years later they moved into the Creeks, which from then on was their year-round home.

The Italianate mansion became a hive of artistic activity. Pollock and Krasner, Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, and Mark Rothko, among others, all came to dinner. There were frequent piano concerts too, organized by Mr. Dragon and attended by as many as 400, whose admission fees went to benefit Guild Hall. “It was a magic time,” he told The New York Times soon after Mr. Ossorio’s death in 1990, recalling the house lighted by 1,000 candles and costumed opera singers wandering through its halls singing Mozart.

With a flair for design and a strong theatrical streak, Mr. Dragon was the one who arranged the furniture and artwork in the mansion and oversaw the table settings for the dinner parties, with inventive themes and elaborate flower arrangements. The Pollock biographer and art critic B.H. Friedman, who was often a dinner guest, once remarked that “Ted could take a weed and make it extraordinary.”

He loved to cook, too, and did needlepoint well enough for an exhibit at Arlene Bujese’s former gallery here. When the Seafood Shop in Wainscott first opened and business was slow, he brought in some paint, found some blue-and-white material in the basement, added white sheets and a few paintings, and changed the look of the place completely. Business picked right up.

But over four winters in the late ’50s there came a strange interlude in Mr. Dragon’s charmed life: He took to stealing valuable pieces of antique furniture from the shuttered homes of his summer-colony neighbors, Robert D.L. Gardiner’s, on Main Street in East Hampton, among them. He hid the items in a large room or attic at the Creeks, where he worked on them for hours, refurbishing and restoring them to their original splendor. The house was so big — 40 or so rooms, some of which Mr. Ossorio never went near — that he had no fear of discovery.

Finally, in the winter of 1959, someone spotted him maneuvering a chair out of a second-story window and called the police. According to Gail Levin’s recent biography of Ms. Krasner, his only explanation was that he “just loved beautiful things so much, and sometimes I was appalled at how badly the furniture was being kept.”

Several prominent East Hampton citizens intervened to help Mr. Dragon avoid a prison term. After undergoing analysis with a psychiatrist specializing in the criminal mind, he spent two years at a private sanatorium in Connecticut, where he gave lessons to other patients in ballet and needlepoint.

A quarter-century later, a passing reference to the thefts in this newspaper called forth a flood of angry letters to the editor. Many protested that bygones had better been left bygones and praised Mr. Dragon as a man who, as Mr. Friedman wrote, had “since his illness been a conspicuously generous member of the community.” The letters kept coming for more than a month, until Mr. Dragon himself wrote in to put an end to them, thanking The Star for opening “a big can of love” for him which he had not known existed.

Mr. Dragon’s friendship with Lee Krasner blossomed after Pollock’s death in 1956. He helped her shop for furniture and antiques and told her where to place them. Helen Harrison, the director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs, said he was “a font of information. He had wonderful recollections of Jackson and Lee that he shared with us for our archives. The big oval table in the dining room? He and Lee bought it at Nielsen’s in Southampton. And each piece had a story attached.” When Ms. Krasner died, she left Mr. Dragon an Empire-period back-to-back loveseat made from Texas longhorn, which he, a fan of horned furniture, had helped her pick out in Manhattan many years before.

By the time of Mr. Ossorio’s death, all the valuable art at the Creeks had been sold. In the end, after spending millions to create an arboretum there that the American Conifer Society called “the eighth wonder of the horticultural world,” Mr. Ossorio was hard pressed to maintain the estate, with a staff of about 30 and yearly upkeep running into the hundreds of thousands. Along with the house and land, he left Mr. Dragon $100,000 in cash and “any birds and dogs I may own.”

Mr. Ossorio had hoped that the Creeks might be preserved as a center for a charitable institution, but it was not to be. Soon after Mr. Perelman bought it in 1993 for $12 million, Mr. Dragon moved to a house on Pantigo Road in East Hampton, where he remained for the rest of his life. In the mid-’90s he established the not-for-profit Ossorio Foundation, to “educate the public on the life and work of Alfonso Angel Ossorio y Yangco.”

He spent his later years quietly. He went to Mass at Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church in East Hampton every day, and donated generously to the church. He also helped his friends with cash gifts when they needed it, but he lived simply. His only known survivor is a sister-in-law in Northampton whom he apparently had not seen for many years and who did not want her name mentioned in reports of his death.

Mr. Dragon, who was born Edward Dragon Young but dropped his last name as a young man, died at home. He was cremated. The disposition of his ashes is not known.