Terror in Tinseltown

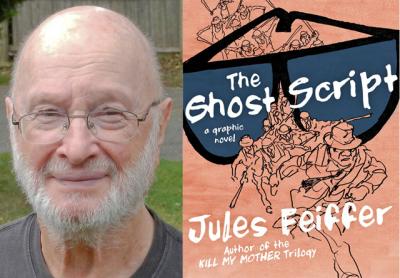

“The Ghost Script”

Jules Feiffer

Liveright, $26.95

Sam Hannigan was a two-fisted, Depression-era detective — he’d brawl with a buddy as a way of shaking hands; he was all-American yet open to immigrants, as long as they’d sign on to the American Dream, looking for freedom, not handouts. He is also just one of any number of specters spooking the margins of “The Ghost Script,” the concluding volume of Jules Feiffer’s noir trilogy of graphic novels, which first raked in the accolades four years ago with “Kill My Mother.”

Outwardly if not in profession, Sam calls to mind Fred MacMurray in “Double Indemnity,” the 1944 movie, though you’ll be hard pressed to find him uttering a line as choice as “I wonder if a little rum would get this up on its feet,” eyeing a glass of iced tea in hand. That’s from a Raymond Chandler and Billy Wilder script, based on the James M. Cain novel, of course.

Sam’s the hero of the trilogy’s second book, “Cousin Joseph,” and he’s missed in this final installment, as previously he brought clarity and focus to a gritty tale of union busting and jingoism, which now wraps up 20 years later in a nebulous story of Hollywood in the blacklist era of the early 1950s.

About Chandler, when Howard Hawks was making his novel “The Big Sleep” into the 1946 film noir, the director cabled that the plot didn’t entirely make sense. “Who killed the chauffeur?” Or words to that effect. “No idea,” came the writer’s response.

Here, the story becomes hard to follow, even convoluted, such are the number of subplots and characters. There’s Sam’s blind widow, Elsie, for one, reinvented as radio’s “Miss-Know-It-All, your official glamour gal of gossip,” and their daughter, Annie, for another, likewise trying to make a go of it in Tinseltown, as a director and writer — in fact, she’s the one who comes up with the idea for a “ghost script,” ostensibly to expose the Hollywood blacklist and those responsible for it.

One of whom, the so-called Cousin Joseph, a Red-baiting, New Deal-hating Methuselah behind Our Forefathers for Freedom, a kind of film code authority committed to rooting out “communist and pro-communist sympathies” in all facets of production, at one point turns a detective’s questioning into a disquisition on the America “you have never seen,” before regulations and unions, in other words, as he putters about in his vast greenhouse modeled after General Sternwood’s in “The Big Sleep.” (Speaking of.)

The rabbit hole of summation and explication will not be entered here, but one element at work is that a clearinghouse has been set up in which blacklisted screenwriters toil under pseudonyms for a cut rate. Movies get made, people are employed, the public’s morale is kept up — er, everybody wins, right?

This plot, or something like it, has been roiling in Mr. Feiffer for decades, ever since the lefty playwright Clifford Odets returned, seemingly triumphantly, after being “lost in Hollywood hackdom for years,” Mr. Feiffer writes in his foreword, only to turn and promptly “name names” as a friendly witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“Am I going crazy?” Mr. Feiffer thought. “What kind of country am I living in?”

Graphically, the draftsman is as expressive as ever, not to mention cinematic in his sepia-toned storytelling, with what you could call crane shots, tracking shots, point of view — all of it put to good use.

The trademark balletic violence beautifully recalls his mentor, Will Eisner, whose most famous character, the Spirit, perpetually beaten up, constitutes yet another allusion, this one from the mouth of the similarly slapped-around Archie Goldman. (“Did I win that one?” he thinks after one of his antagonists drops dead of a heart attack mid-fight. “Do I know the difference between losing and winning? Can you live your life without knowing the difference?”)

A kid in “Cousin Joseph,” Archie has grown to be a detective like his hero, Sam Hannigan, but a schlub of one, so plagued by self-doubt that one night in the desert he drives in circles of indecision, talking to himself, over a full seven pages in what might be the most realistic sequence in this book of sequential art. Until, that is, the deus ex machina ending.

But that’s the world we live in, isn’t it.

Jules Feiffer lives on Shelter Island. He’ll be at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor on July 28 at 5 p.m. and at the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night on Aug. 11 in Amagansett.