The Things Forgotten

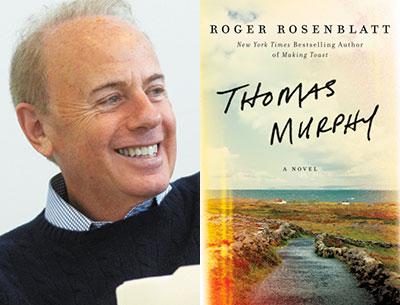

“Thomas Murphy”

Roger Rosenblatt

Ecco, $24.99

I must admit to some trepidation about reading and reviewing Roger Rosenblatt’s new novel. His wonderful memoir “Making Toast” — about the sudden death of his 38-year-old daughter and how he moved in with her family, along with his wife, to provide care and comfort — never crossed the line from tender sentiment to sentimentality. But a brief summary of “Thomas Murphy” gave me pause: An elderly Irish-American poet meditating on loneliness and loss meets a young blind woman facing loneliness and loss. How could Mr. Rosenblatt pull this one off without succumbing to some easy, sappy resolution or utter bathos?

Thomas Murphy, born in Inishmaan, a tiny, sparsely populated island between Galway Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, is now a recently widowed senior citizen on the teeming Upper West Side of Manhattan. He’s become somewhat absent-minded, to the distress of his only child, a single mother named Maire. In the “brain” doctor’s office, where Murphy goes at Maire’s urging, he’s all carefree bravado. “Look at me! I know what year it is. I can spell syntax. And recommend. If they asked me, I could even recommend a syntax.”

On his own, though, he’s on shakier ground, as he mourns his dead (he still looks for his lost wife, Oona, in every room of their apartment, “just in case”), ruefully contemplates the persistent passage of time, and replays old regrets. Why didn’t he ever answer a fan letter from his poet-hero, W.D. Snodgrass? And then there’s the business of misplaced house and car keys, and an unwatched, burning pot of eggs. Maire’s uneasiness about her father’s welfare might not be unfounded.

Yet Murphy still functions at a high level. His literary memory is intact, and his responses on the take-home neuropsychological test the doctor gives him are sharply smartass, and often hilarious. A question about balance problems leads to an answer about balancing his checkbook. To another, regarding his ethnicity — Asian? Black? Hispanic? White? Other? — he replies, “All of the above, just like you, you racist bastards.”

He leads a poetry workshop at a homeless shelter, where he perceives nearly all of his students as schizophrenic, unable to make narrative connections. But he concludes, “What’s anathema for normal social life is meat for the poet,” and that “Somewhere in the holy messes of their minds, they would prefer to be pain free, not poets.”

As for himself, poetry is simply a way of life, sparked in childhood by his “unshaven, baritone da of the red creased neck and the whiskey breath” reading Yeats and Padraic Colum aloud to him. Murphy takes his beloved 4-year-old grandson, William, out for walks and lively conversation in Central Park, and, while Maire (presumably) and the reader nervously hold their breath, brings him home again, safely.

Sarah, the blind young woman, enters Murphy’s life in an entirely offbeat way. One evening at a favorite drinking hole, he’s recognized (from a newspaper photo) by a stranger at the far end of the bar. The man, Jack, who sidles over, has a mission. It turns out that he’s going to die within a few months, of colon cancer, and needs a “good poet” to break the news to his poetry-loving wife. He’s apparently too inarticulate to do it himself. What an idea! Of course, Murphy declines. He doesn’t know these people; this should be a private moment between husband and wife, etc. etc. But Jack is persistent and eventually sends a photograph of his Sarah to Murphy, whose reaction is instant and visceral.

“Naturally, I looked first at her eyes, which were gray and did not seem blind but full of wit and knowing. . . . Male that I barely still am, of course I studied her breasts.” Her picture is propped on his writing desk next to a drawing of John Millington Synge. Murphy thinks, “I don’t know why. Now she did not seem so alone.”

Aloneness is one of his — and this novel’s — abiding concerns. Although he professes to having “failed every subject except solitude” in school, he admits that “living alone is one thing. But dying alone?” Death, too, is often on his mind, or “Mr. Death,” looking like “Wallace Stevens with a scythe” (no offense intended).

Murphy doesn’t act right away on Jack’s bizarre request, and when he finally does, it’s Sarah’s picture, rather than her husband’s pleas, that compels him. As he sees it, he and she “are old friends who have yet to make each other’s acquaintance.” So he finds himself in Jack’s red Corvair, heading for Queens. On the way, Jack refines the terms of their contract. Could Murphy just get to know Sarah — say, in four or five visits, before they “lower the boom”? This is far more than Murphy bargained for, but his pity for Jack and curiosity about Sarah “of the bittersweet smile” lead him to a compromise agreement: two visits and then they break the bad news to her.

But sightless Sarah sees right through their scheme. She knows that Murphy has been assigned to tell her that Jack is dying, in some loopy version of Cyrano de Bergerac.

She knows a lot more than that, actually, but this isn’t a spoiler alert; I won’t reveal the surprising plot twist she discloses to Murphy during a meeting alone with him that she’s set up. Let it suffice to say that she enters his life in a significant way just as his cognitive losses begin to pile up. The forgotten ZIP code, the front door left wide open, the sudden “liquefying” of West 86th Street as he tries to make his way home, and, perhaps worst of all, Maire’s realized suspicion that he’s suffering from hallucinations.

She and the doctor aren’t persuaded by Murphy’s alliterative celebration of his situation. “But think of the fullness in forgetfulness — the universe of thought and feeling that forgetfulness replaces for the things forgotten.” A brain scan is ordered and the damage defined: beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, hippocampal atrophy, like words from a new language. “Some science shit,” in Murphy’s opinion, but he agrees to a blood test to confirm or disprove a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, his mother’s disease.

In the meantime, there’s another blow: Maire announces that she and William are moving to London, where she has an important job offer. Murphy is stricken by the news — “Christ, what will I be doing walking in Central Park without my little man beside me?” — but puts on a typical, swaggering front. “I give her a hug nonetheless, and tell her it’s great and that she’s great and the job sounds great and that I’ll be great. . . .”

At least there’s the continuing presence of Sarah — their increasingly intimate conversations, her charming letters to him, and his to her, and the ultimate marvel of their lovemaking. She’s the perfect antidote to his feelings of grief; they seem to share a singular vocabulary and a single sensibility. He’d had a comparable oneness with Oona.

Is this what I feared — the author’s convenient copout for the sake of a neat ending? Happily, no. But is Sarah only a temporary tourniquet for Murphy’s fresh psychic wound? Or has he just made her up out of his own longing, with a poet’s desperate, fertile imagination? As we used to say in middle-school book reports, read it yourself and find out. You’ll be glad you did.

This is the sort of novel you mark up with pleasurable abandon, so that you can read passages aloud later to someone else, which it seems I’ve done, in a sense, in this review. “Thomas Murphy” is so well written, it was difficult not to.

One often wonders which parts of a novel are autobiographical and which are fictional. I suspect that some of the exchanges between Murphy and Maire and William come from Roger Rosenblatt’s own experience, from similar exchanges with his daughter and his grandchildren. In all good fiction, fact and invention often mingle and blur. What matters in the end is that the whole contains, as it does so strikingly here, both hard and consoling truths about how we live.

Hilma Wolitzer’s novels include “An Available Man” and “The Doctor’s Daughter.” She and her husband lived part time in Springs for many years.

Roger Rosenblatt teaches at Stony Brook Southampton and lives in Quogue. “Thomas Murphy” comes out on Tuesday.