Three’s Company at the Parrish

Despite what many people assume, the artists who practice on the East End still make up a small community; it is just spread out a bit. Nonetheless, it took a couple of outsiders, coming from Texas, no less, to remind us all.

Since Terrie Sultan became the director of the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton, she has overseen an eclectic schedule of exhibits, some global in their reach and others hyper-focused on the South Fork or on elements of the museum’s permanent collection. The Parrish has always had a juried show, but typically one critic or a handful of critics and academics has done the choosing.

When Ms. Sultan arrived a few years ago from the University of Houston, where she ran the art museum, she decided to bring the selection down to the level of the artist. Not only would a few artists choose other artists they liked, they would also try to find work that would make sense placed next to their own on a wall. The first show, “Mixed Greens,” showed how informative such a selection process and exhibit could be.

This year, the idea has expanded under the guidance of Andrea Grover, the museum’s associate curator, also recently arrived from Texas, but originally from Long Island. The “jury” of artists chosen by the Parrish would each ask two artists to join them. Dan Rizzie is one member of that jury. He is a longstanding member of the South Fork artist community who, it turns out, also hails from Texas. He now lives on North Haven and said having strong local ties made the selection process particularly difficult. He is friends with many of the artists who submitted work.

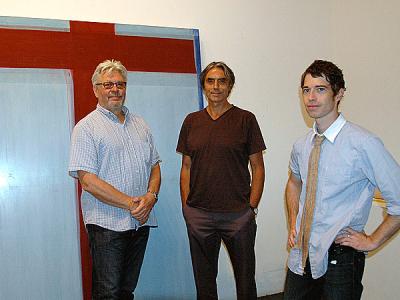

“It was not easy. We had 200 works to go through, and it was strong, very strong work,” he said in the Parrish’s galleries on Aug. 18 as staff members installed the show, called “Artists Choose Artists.” The two he selected were with him.

He said his choice of Tad Wiley and Ross Watts came down to their approach to surface as well as an architectonic quality, which is important to all three of them. Some of that has to do with their shared choice of support, which is wood, but Mr. Rizzie said their individual results are “all quite different. It’s an interesting thing.”

That early sense became more apparent during the follow-up studio visits that jurors undertook with their shortlist of artists. “When I was looking at that work, a bell went off,” Mr. Rizzie said. “I don’t know how the other jurors and applicants went about it, but the three of us fit nicely together, and seeing our work together today confirms that.”

Mr. Wiley, whose “Two Trees,” an oil-base enamel on panel painting from 2010, is in the show, said his preference for wood came out of a desire that began in art school to make paintings in odd shapes. “To make eccentrically shaped canvases or stretchers was a lot of work,” he said. Cutting wood panels to the shape he wanted became a more viable option.

He said he found the support more accommodating to the way he painted as well. “I was using acrylic and sanding it back. I don’t like buildup.” The choice worked for him on all levels, he said, even as he gradually moved back to a more traditional rectangular format. His paintings still have a kind of fossilized, floating spiritual quality, alluding to a physicality that has been washed or abraded away, leaving only traces of what once existed. According to Mr. Watts, his need for a lot of sanding in his work also led him to wood. “There were some practical issues, and I never was really much of a painter.” His works are more akin to sculptural forms that are free-standing or hung at a distance away from the wall. “Stasis,” from 2010, is a group of 14 panels painted in white acrylic and distressed, using staples and other “flaws,” such as nail holes and a suggestion of a prior paper label. The artist places each of these elements in a similar pattern. “I always felt like I built these things. There was a lot of collage, a lot of paint, and a lot of sanding,” he said.

Mr. Rizzie said he started using wood in graduate school in the mid-1970s. “I didn’t really know what I was doing. I didn’t call myself a painter or call these things paintings. Plywood made sense because I could buy a 4-by-8 sheet and cut it up.”

He said he was rough on his wood objects. “I would beat them until they became something,” working with clay on the surface. He now uses paint and collage. He has a rich graphite work on paper mounted on panel in the show. Called “Five Barns/Black,” it is from his early days as an artist and has small, minimal structures as its composition. “I tried it on canvas, believe me. This just worked better.”

From his discussions and observations, he said, “there is an object quality to all of our work. They hang on the wall and are all somewhat traditional, but they are also objects, as opposed to making just flat paintings.” He said he didn’t necessarily feel like a sculptor, but he did always feel as if he was making a thing. “I didn’t want to define it as a painting, drawing, or collage.”

Mr. Watts agreed about seeing his work as an object. “There is also this back-and-forth between that and the awareness of its surface,” which brings it back into the realm of painting.

“Obviously process is important to all of us,” Mr. Wiley said. “Even collaging is almost a sculptural endeavor, but we’re still dealing with the pictorial. I kind of like the rectangle as a pictorial element. It makes sense to me to make images that reiterate that format of the horizontal and the vertical.”

The exhibit is on view through Oct. 9 and will feature gallery talks and other events. There is more information at the Parrish’s Web site, parrishart.org