The Thrill of Chick Noir

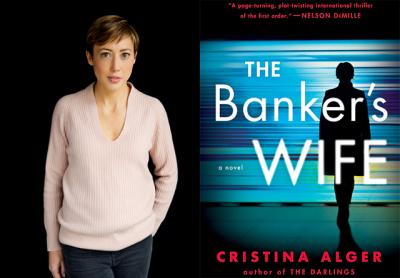

“The Banker’s Wife”

Cristina Alger

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, $27

The domestic detective appears to be having her moment. Amid all the “girl” thrillers — “Gone Girl,” “The Girl on the Train,” “The Good Girl,” “The Girl Before,” and “The Perfect Girl” — we now have the “wife” suspense novels: “The Silent Wife,” “The Wife,” and “How to Be a Good Wife.”

Domestic noir, as the author Julia Crouch coined the genre in 2013, usually involves a crime surrounded by twisting plots, creeping unease, and sly insistence that the home isn’t a haven but rather a place where anything and everything can go wrong. At the core of these stories are women who are often smart yet far from independent, who are weak, confused, and overly reliant on men, but who, in the end, get their comeuppance.

Into the milieu comes “The Banker’s Wife” by Cristina Alger, a part-time Quogue resident and New York City native who was a Goldman Sachs analyst and a corporate attorney before becoming a writer. This is her third novel, following “The Darlings” in 2012, which concerned a family of enormous Wall Street wealth brought down by a Ponzi scheme, and “This Was Not the Plan” in 2016, about a top-flight workaholic lawyer who is forced to reconsider life’s priorities.

“The Banker’s Wife” has two female protagonists, both of whom, like most of the female characters in this story, are stunning, intelligent, of Ivy League pedigree, and professional — although one has shelved her career to follow her banking husband to Geneva and the other is about to give up work to become a more acceptable socialite wife.

The story begins with the death of the banking husband, Matthew Werner, whose private plane crashes in the Alps, also killing his fellow passenger, the mysterious Fatima Amir, a hedge fund investor with ties to the corrupt Syrian regime and who is blessed with “striking, photogenic features: a strong Romanesque nose; pronounced cheekbones; full, sensual lips.”

Meanwhile, Annabel Werner, the banker’s wife, learns of her husband’s death as she awaits his return in their luxurious Geneva apartment “wearing a black cocktail dress and the long sable coat that Matthew had bought her when they first moved to Switzerland. A hairdresser on the Cours de Rive had coaxed her auburn hair into a twist. Her shoes, five-inch pumps that a salesgirl in a boutique on rue de Rhone convinced her to buy against her better judgment, pinched at the balls of her feet. In the dressing room mirror, the shoes had made Annabel’s legs look impossibly long and slim.”

Despite having it all, Annabel is unhappy and drifts through her affluent Swiss life like a less vivacious Emma Bovary. She is bored and listless, but “not wanting to be a stick in the mud,” she suppresses her needs and growing loneliness to play the beautiful, dutiful wife. Until, that is, Matthew’s death, when she realizes it’s time to kick off the stilettos and start playing Nancy Drew instead.

Alternating through the plot is Marina Tourneau, an investigative journalist, who is engaged to Grant Ellis, a well-connected investment banker whose father is preparing to run for president of the United States. Despite her passion for her job, and her rise to the top of Press, a New York-based magazine, Marina will soon be quitting because “there were things one had to do to be the wife of a C.E.O. of a multinational corporation. Not to mention the wife of the president’s son, should it come to that. She couldn’t work and be Mrs. Grant Ellis. At least not at the same time. There was no question what was more important to her. She had to quit.”

But there is one last story she simply cannot resist: the truth behind Matthew Werner’s death and that of her mentor, which, once she starts digging, uncovers corruption and moral high jinx among some of the most powerful men in finance and politics.

Into the plot comes Matthew’s beautiful young assistant, Zoe, who even in the middle of the night “looked fresh-faced and chic in black jeans, high-top sneakers, and a fur vest. Her skin glowed in the dark hallway, the moonlight glinting off her high cheekbones.”

Zoe reassures the grieving Annabel that Matthew’s love was unwavering and also produces Matthew’s laptop, on which he had secretly compiled evidence against Swiss United, where they worked, after he discovered the bank was doing business with terrorists, arms dealers, and dictators. Why Matthew would tell his assistant such damning details is one of many looming but unanswered questions.

Nonetheless, the pacing of the story is particularly lively. There’s plenty of suspenseful plotting and a quest for conclusive answers as the story swings convincingly between Geneva, Paris, London, New York, the South of France, and ultimately, the Caribbean.

But unlike many of the “girl” and “wife” thrillers, which tend to be less about the investigation of a mystery than about psychology and the shifting perception of what we think to be true, “The Banker’s Wife” offers little in the way of insightful character development. Too often, characters and their relationships with each other are so overidealized that their trajectories are telegraphed well in advance. The story appears to be written not to mine a reader’s imagination but to pique the interest of Hollywood.

Yet even a flawed crime thriller like “The Banker’s Wife” serves a useful purpose in today’s tumultuous world in which political corruption, violence, and gender politics have gained fresh relevance. For in times of uncertainty we often seek redemption and resolution. And what could be better than getting lost in a book in which good triumphs over bad? Where evil is punished and the good guys mostly win after solving the puzzle?

It helps put the balance back in life and makes all seem right with the world. Even if only fictionally.

Cristina Alger will be at the Quogue Library on July 29 at 5 p.m. and at the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night on Aug. 11.