Time Bandits

“Gertie Milk &

the Keeper of Lost Things”

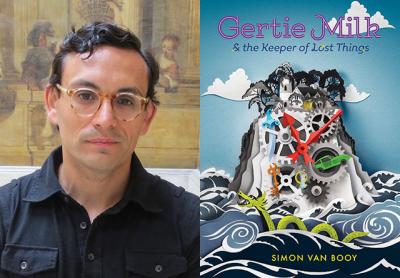

Simon Van Booy

Razorbill, $16.99

I’ll be honest, and honestly I don’t particularly want to be honest, as I consider myself a fan of Simon Van Booy’s — from his recent entirely successful novel, “Father’s Day,” which out-realisms realism, to his heartfelt short stories, his Welsh background, his fin de siecle good looks. But with “Gertie Milk & the Keeper of Lost Things,” his new novel for young readers, I had trouble telling what was comedy and what was simply a lark.

Wait a minute, you’re thinking, it’s a middle-grade novel, where do you get off laying on such criticisms in the first place? Because, reader, the beginning’s so strong. Consider: A 12-year-old girl washes up on a deserted beach, could be anywhere, in nothing but a nightgown and slippers — no memories, no identity beyond a name sewn into her soaked attire. “All around there were boulders covered with slick sea grass, like the wet fur of some once-terrible creature that had not risen for a thousand years.”

Later, “Her missing memories might have been close, just a few thoughts away, but trying to remember felt like going around a corner that never ended.”

Time slippage is at play. What with the large wine stain birthmark on Gertie’s cheek, visions of a David (“Cloud Atlas”) Mitchell adventure danced. Uh, for young readers.

But such lyrical writing, nothing new to Mr. Van Booy, doesn’t return.

As she walks the island of Skuldark, which is of the earth, only existing a bit like the unseen space between the walls of a house, Gertie chances upon Kolt, his name an acronym for his position as the sole remaining Keeper of Lost Things. He’s the size of a golf tee at first, having ingested, Alice-like, some shrinking spice when he meant to grab the growing spice (an element of the plot that is not revisited). The Keepers are an order charged with selecting the choicest of misplaced items and returning them, in essence to make people less fearful, fear being the root of all our problems. Gertie is the new recruit.

The vast collection of lost things sits in chambers off labyrinthine passageways beneath Kolt’s cottage, where he lives in British eccentricity, eating peach cake and sipping tea like (I’m sorry, once you start thinking this way you can’t stop) a well-dressed Mr. Tumnus from C.S. Lewis.

And his contentment is similarly sundered, as outside the cottage lie scattered the larger lost items, camouflaged World War II-era fighter planes, for instance, and among them a (yes, again) Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang heap of an old Jaguar, the vehicle that will transport Kolt and Gertie through time.

One of their stops is a hollowed-out Los Angeles after the Information Wars. People have fled for floating cities beyond the earth’s atmosphere, and the planet has been turned into a giant community garden.

That’s all intriguing, but unfortunately it’s a fleeting visit, and what we’re left with is a sidekick, Robot Rabbit Boy, about the size of a Cabbage Patch Kid and equally worthy of an ax handle to the midsection. The product of a genius toymaker who went off her nut, he’s metallic, his speech is limited to a few nonsense phrases (“Eggcup,” he chirps), he’s weaponized with a laser that shoots from his button nose — he’s not funny.

But all is not lost, if you’ll pardon the pun, as Mr. Van Booy, who has written books on philosophy, strives to get some profundities across to the reader, in the form of lessons Gertie learns on her hero’s quest or even her own realizations. Fear not death, for one. “Remember,” Kolt tells her, “the human body isn’t the start of life, it simply holds it for a moment, the way you can fill a cup with water from a slow, deep river. Even if you empty the cup, the river flows on, and the water becomes rain, or snow, or mist. . . .”

Heavy stuff, leavened incessantly by stabs at humor: “You may not know this, Gertie, but for the first 180,000 years, our species of human lived short, painful lives with lots of hair and no shampoo.” Prehistory, furthermore, was a time when “even just showing up unannounced with fairly good teeth was a good enough reason to be burned alive or thrown into the cooking pot with a potato or two.”

The enemy across time, it should be said, is a roguish band called the Losers, who “want to strip the world of ideas, and destroy all technology so that humans can start again — having made such a mess of things,” Kolt says, and Gertie can be forgiven for feeling conflicted, given the logic of that aim.

But Gertie, her 12-year-old wisdom enhanced by encounters with such learned figures as Eratosthenes and Lao-tzu, comes to see human progress “as brave people holding hands in a long line, passing ideas to one another. . . .”

That’s right, kid. Keep hope alive.

Simon Van Booy earned an M.F.A. in writing at Southampton College. He is a former South Fork resident and remains a visitor.