Tonight’s the Night (Or Is It?)

“Only You”

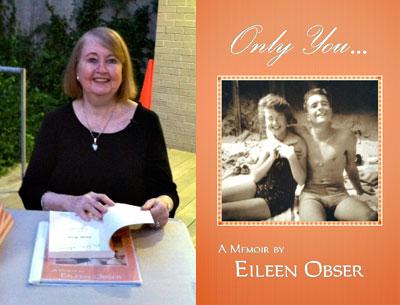

Eileen Obser

Oak Tree Press, $14.95

Eileen Obser, freelance writer, editor, and teacher, has written a book about sex.

Now that I’ve gotten your attention, “Only You” is a memoir about her experience as a 1950s teen bride in Queens, unable to give her young husband, Billy, what he clearly wants and expects on their wedding night. And every night thereafter — daytimes too — though it’s not for her lack of trying.

She’s scared and he’s persistent. “What’s the matter with you, anyway?” he asks after his honeymoon advances fail to arouse her.

Worried that something is wrong with her, but intuiting that her mother would not be the one to ask — months before, she had told her young daughter that she was relieved her husband “doesn’t bother me anymore” and “finally leaves me alone” — she bears her burden silently, too humiliated even to share her secret with a beloved aunt.

Sometimes “trying,” other times putting Billy off with “later,” often faking sleep to avoid sex, always dreading the night, Ms. Obser finds herself with nowhere to turn.

Using song titles of the era as chapter headings, Ms. Obser evokes Lindy Hops, a candy store crowd, and good middle-class Catholic girls not “doing it” till they marry — marriage being a ticket out of her parents’ house, with their quarrels and constant bickering about money, of which there never seems to be enough.

A ticket out of one problem, maybe, but an express train to another — her handsome husband is possessive and could be crude and obnoxious. The intimacy she believes sex will bring eludes her.

Wondering if she would feel differently “with another guy,” she remembers Augie Vrondis, her “biggest teen crush,” and a dance contest they won.

“We moved dreamlike, possessed. Round and round, back and forth, swinging, swaying. Come close, get wrapped up in each other’s arms, soooo close, then separate. Do it again.” A joy in movement.

Her emotional pain and desire for more in her marriage made clear, Ms. Obser again recalls better times, and in one of the book’s livelier scenes — I often found the narrative lacked momentum, with sundry details about what characters said and wore slowing it down — she tracks back to her father, Albert Kirchner, previously drawn as humorless and stingy, now mimicking Edward R. Murrow interviewing a celebrity.

“It’s good to see you, Ed,” my father said, taking him to our bay window and pushing aside the limp, off-white curtains. “As you can see, we have quite a view from here,” and his hand swept . . . a view of the tops of more houses, a few trees, the railroad tracks and a cemetery to the left. . . . “This is a little something from our art collection,” he said, pointing to a faded, stained Currier & Ives print that had hung there for as long as I could remember.

. . . He kept it up, showing “Ed” all our family treasures — ashtrays, beer glasses, the inside of our coat closet, stains on the rug, until my mother, Buddy [her cousin], and I laughed so hard our stomachs ached.

A year and a half into her marriage and still a virgin, Ms. Obser takes matters into her own hands.

She consults with her priest. She sees a doctor, telling him of “the stomach spasms, dull aches and heartburn” that plague her when it’s time for bed. A simple surgical procedure solves the physical side of her problem. She can “do it.” But in an odd turn of events, now that she’s willing and able, Billy has other ideas. Annulment is what he’s thinking; he’s found someone else.

“Cast aside, rejected by [her] husband,” the ending of her marriage feels like “the death of all thoughts of love and happiness.” But Ms. Obser rallies. She gets a job, her own apartment, and takes college courses — she’d wanted to go to college for a long time, but Billy wouldn’t allow it, and she had “no idea how to even begin to accomplish such things.”

“In just a few years,” the ending paragraph tells the reader, Ms. Obser “would have a new man” in her life. One whom she would marry and with whom she would have children. I would have welcomed more about this new man, the circumstances under which they met, and how he differed from Billy.

Not skittish about discussing the complications in her early marriage, Ms. Obser takes on the dicey subject of sexual dysfunction — a word unknown at the time — in a forthright and honest manner, not blaming herself or Billy, but fixing the end of her marriage to the notion that the “kids,” as she calls the two of them, were “perhaps too young and ill-informed to make a marriage work.”

Rita Plush is the author of “Lily Steps Out,” a novel, and “Alterations,” a book of short stories. She lives in Queens and East Hampton.

Eileen Obser lives in East Hampton.