Town Ban Sidestepped by State, Corps on Montauk Plan

United States Army Corps of Engineers staff and New York State officials have sidestepped East Hampton Town in moving ahead with a planned multimillion-dollar project to protect the downtown Montauk ocean shoreline without obtaining local authorization.

Under a 2007 town law that divides the shoreline into four zones, as well as an earlier policy, the project, which involves approximately 14,500 sandbags and thousands of tons of fill placed on the beach for an indefinite period, is prohibited. A provision that would allow a short-term, six-month alternative with a possible one-time extension has not been invoked.

In letters sent to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Town of East Hampton, Carl Irace, a lawyer representing the Surfrider Foundation, said officials had misinterpreted the town’s policies.

A review of Army Corps documents suggests that it did not consider a key section of town law when preparing for the work last year. A line-by-line analysis by the corps of the East Hampton Town Local Waterfront Revitalization Program, which requires that New York State and federal agencies follow its regulations, did not include any reference to the 2007 portion that sets policy for coastal permits.

In the town’s Zone 1, where the downtown Montauk project is planned, the law allows sandbags, or geotextiles, on the ocean beach only on a short-term, emergency basis. Emergency permits can be obtained from the town’s building inspector to defend property deemed in imminent peril, provided that the work is “immediately necessary to protect the public health, safety, or welfare, or to protect publicly or privately owned buildings and structures from major structural damage,” the law states.

In addition, even when permits are obtained they are subject to strict limits. The town’s emergency erosion-control regulations require that provisions must be made at the time the permits are issued for the eventual removal of sandbags.

“Neither the federal nor state government has the authority to usurp the town’s sovereignty over coastal consistency review of projects within town jurisdiction,” Mr. Irace wrote.

“This is a really important topic, and everybody is getting this wrong, as wrong as wrong could be,” Mr. Irace said in a follow-up interview this week.

Laz Benetiz, a spokesman for the Department of State, and other officials reached for comment said the downtown Montauk project was considered temporary because the Army Corps viewed it as a first step toward the far-larger Fire Island to Montauk Point Reformulation Study. Known as FIMP, it was authorized by Congress in 1960.

However, an Army Corps document variously described the Montauk work as satisfying a state requirement that the project “have a reasonable probability of controlling erosion for at least 30 years” as part of the Fire Island to Montauk Point project, as well as having a 15-year “project life.”

“You can’t argue this is temporary, particularly when the town sets six months as the definition of temporary,” Kevin McAllister, an environmental activist and founder of Defend H20, said.

“You could use that argument taken to its extreme that anything is good because you are waiting for FIMP,” said Mike Bottini, a naturalist and consultant who chairs the Surfrider Foundation’s local chapter.

Roughly $233 million for Army Corps projects in New York State was included in Congress’s $49 billion Hurricane Sandy Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013.

Chris Gardner, an Army Corps spokesman, said in an email earlier this month that if local permits were required for the Montauk work, the company hired to do the work would have the responsibility of obtaining them. He was not able to respond to a follow-up request for clarification.

“This is one of the craziest projects I have ever reviewed in more than 25 years of environmental planning,” Mr. Bottini said.

Proposals from contractors seeking to take on the downtown Montauk job were to be submitted by Tuesday. Bids will be opened and examined next week, Mr. Gardner said.

Concern about the high-risk exposure of the downtown Montauk oceanfront goes back at least a decade. In 2005 the Town of East Hampton briefly considered creating an exemption for the properties there that would have allowed structural erosion-control measures of the sort being prepared by the Army Corps. That idea was dropped, and when the Department of State signed off on the town’s Local Waterfront Revitalization Program two years later, the area had been put in Zone 1, where none are allowed.

The section of the law setting coastal erosion zones was the final, long-delayed step before East Hampton Town’s L.W.R.P. was approved by Albany. This was no mere formality; state-sponsored actions and some federal projects from that date forward had to, at least on paper, be consistent with town law.

For projects being contemplated along the shore, this meant that the state would no longer take the lead.

According to the Department of Environmental Conservation website, East Hampton Town, along with 41 other local governments in the state, administers its own coastal erosion management permits, though related approvals from other authorities can also be necessary. Nevertheless, the D.E.C. has been named the lead agency for the Montauk project.

Like the Town of East Hampton, East Hampton Village, Sagaponack Village, Southampton, Southold, Brookhaven, and Riverhead are all listed as certified by the D.E.C.

“Why did we go through the whole painful process of doing the L.W.R.P? Thousands of hours of work were put into that,” Mr. Bottini said.

Numerous requests for a response from the D.E.C. were unsuccessful. East Hampton Town officials, including Elizabeth Vail, the town attorney, were on vacation and unavailable for comment.

In a letter signed in October, Matthew Millea, a deputy secretary of state in the Office of Planning and Development, agreed with an Army Corps finding that the estimated $9 million project conformed to the town’s local laws. Mr. Millea, who is now Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s deputy director of state operations, did not respond to an interview request.

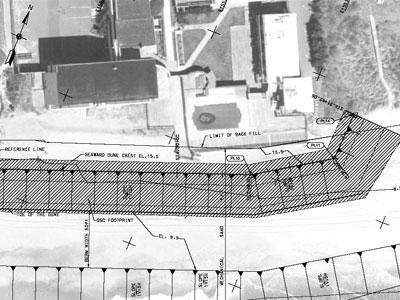

The Army Corps’s six-page review of East Hampton Town’s waterfront laws, released in June, did not address the prohibition on hard structures in the town’s coastal erosion hazard law. And even though the corps acknowledged that the section of the town’s Local Waterfront Revitalization Program that predated the division of the shoreline into four zones, states that “only non-structural measures are permitted to minimize flooding and erosion,” it concluded that the 3,100-foot-long, 14,560-sandbag project was a “non-structural dune reinforcement” activity.

East Hampton Town’s erosion-control law differs on this point, including the bags on a list of prohibited structures. “Any coastal geologist can tell you that this is a hard structure,” Mr. Bottini said.

Peter Weppler, an Army Corps official credited as the author of the six-page review of the town laws, was not available for comment.

In an email, Mr. Benetiz acknowledged the existence of the town’s emergency erosion-control procedure in which the building inspector can issue short-term permits. He did not say if the Department of State had considered the town’s coastal zones law in a broader context and did not respond to a follow-up question.

“Everybody seems to be going along here, and I am troubled by that,” Mr. McAllister said.

Following the insistence of East Hampton Town officials that work on the Montauk Beach be suspended during the summer months, the work, which was to be done as a single project, was divided into two phases. The first, about 1,200 feet in length, is to begin in March on the eastern side of the downtown. Activists have raised questions about whether new environmental assessments should be required now that the work will be done in two phases, and legal challenges are reportedly being contemplated.

Much of the excavation and placement of the sandbags will take place on private property, above the high-water mark, extending in at least one location into naturally vegetated dunes. Work on the Montauk beach would resume on Oct. 1, according to the Army Corps. Because it is difficult to plant beach grass during the summer, the first phase of construction would remain bare until the fall.

“This is destined for failure. There is no way it’s going to work,” Mr. Irace said.

Meanwhile, a similar, if far smaller, project is being planned by four neighbors for the Springs bayfront near Louse Point. Unlike the Army Corps, the property owners have requested variances from the coastal erosion hazard area law. This will soon be reviewed by the town zoning board of appeals. The Springs residents hope to install about 550 feet of rock revetment to protect their houses.

Related stories:

Trustees Urged to Take Stand on Army Corps Project, Feb. 19, 2015

New Detail on Massive Montauk Seawall, Feb. 6, 2015

New Delays, Added Costs For Montauk Beach Defenses, Dec. 24, 2014

State Dismisses Impact Of Army Corps Project, Dec. 4, 2015

State Sanguine on Sandbag Plan, Nov. 26, 2014

Renewed Opposition to Army Corps Plan, Oct. 8, 2014

Army Corps Offers One Montauk Option, April 25, 2014

Town Board Asks for Army Corps Analysis, Oct 24, 2013

Town Okays Erosion Law Just Before Storm, April 19, 2007