Transformative Times

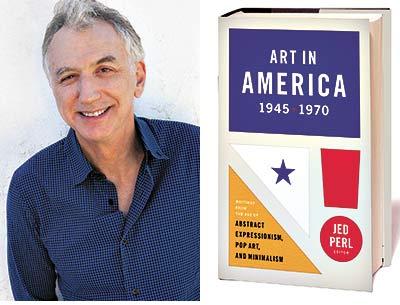

“Art in America

1945-1970”

Edited by Jed Perl

The Library of America, $40

Fast-paced changes in the goals of American artists during the quarter-century following World War II were all passionately felt and widely debated, with many creative voices participating in the effort to define modernity.

Jed Perl’s broad, perceptive selection of material reflecting these voices in “Art in America 1945-1970” makes this hefty anthology an illuminating reference to its era. All the major shifts in sensibility are present, so it is fairly easy to pick up the many ways in which contemporaries were addressing the validity of Abstract Expressionism, then Pop, and then Minimalism.

To best capture the spirit of the dialogue, and to suggest what was in the air, Mr. Perl includes material from well-known and now lesser-known periodicals, and also from exhibition catalogs, books, lectures, letters, and artists’ statements. It is a special pleasure to find the carefully weighed language of poetry appearing here too, in the context of its inspiration. Examples include Howard Nemerov responding to an iron sculpture by David Smith and Frank O’Hara responding to a painting by Mike Goldberg.

As might be expected, chronology propels the anthology along. The pattern adjusts, however, to group together multiple selections by an individual author. This allows a fuller view of an often influential figure. Mr. Perl gives every writer a headnote, which is usually a succinct and pithy career assessment. These interpretive and welcome background overviews stem from Mr. Perl’s long career as a respected art critic and art historian. A considerable amount of the documentary research for this anthology seems to relate to his book “New Art City” (2005), a narrative celebrating New York’s history as a magnet for artists.

Mr. Perl is thorough in presenting the era’s intellectuals, who tend to bring in social circumstances or psychological issues as they address the creative process and analyze artistic content. Four essays offer insight into Clement Greenberg’s influence on taste. Another four provide a view of Harold Rosenberg’s important contributions, including “The American Action Painters,” which points to the viewer’s engagement in the artist’s creative act, and “Mobile, Theatrical, Active,” published a dozen years later, which considers emerging developments.

The selections representing Meyer Schapiro’s probing critique — particularly “The Liberating Quality of Avant-Garde Art” — underscore his role as a champion of the human imagination and his timely fit into the 1945-1970 psyche. Here, too, is Leo Steinberg’s “Contemporary Art and the Plight of Its Public,” which gave Harper’s readers a keener understanding of Jasper Johns and much else. Susan Sontag discusses materials, objects, and the treatment of time in her significant contribution, “Happenings: An Art of Radical Juxtaposition.” There is also piercing commentary on the social impact of the Museum of Modern Art in Dwight McDonald’s New Yorker profile of Alfred Barr, the museum’s first director.

The breadth and probing spirit animating the selections frequently reveal the way differing ideas launched, then developed further within the popular culture. In photography, for example, six writings, dating from 1946 to 1965, divide between either encouraging audience response to the subject depicted, or encouraging response to the design extracted from the original source. James Agee, in an introduction to Helen Levitt’s photography of children on the streets of New York, emphasizes her way of seeing and understanding a face or an emotion; Jack Kerouac’s essay for Robert Frank’s “The Americans” cites Frank’s way of finding “the everythingness of America,” and Truman Capote, writing about Richard Avedon, notes “the blood-coursing aliveness he could insert in so still an entity as a photograph.”

Among authors intent on emphasizing the invention of new art, there is Robert Creeley’s appreciation of the subtle forms in Harry Callahan’s photographs; Harold Rosenberg noting that he finds Aaron Siskind’s photography has “the dual picture planes, calligraphy, the post-Cubist balances, the free strokes and aerial perspectives, the accidental landscapes, galaxies hinted in stains, of half a dozen vanguard styles,” and Siskind himself writing that when he photographs an object, “it is often unrecognizable; for it has been removed from its usual context, disassociated from its customary neighbors and forced into new relationships.”

Artists’ statements, often originally published in conjunction with an exhibition, appear throughout as primary sources. It is easy to feel the passion and conviction. Some have great resonance, such as Robert Rauschenberg’s comment on trying to act in the gap between art and life, and Ad Reinhardt’s statement on purity, “No confusing painting with everything that is not painting.”

Other artists’ statements are especially treasured for the way in which they bring out sources of inspiration. Anni Albers, for example, wrote of the significance of pre-Columbian textiles, and Jackson Pollock’s reference to Indian sand painting is now legendary. So, too, is Willem de Kooning’s discussion of the old masters and their handling of pictorial space.

It is the carefully reasoned essays illuminating new directions that are likely to be frequently consulted. Barbara Rose’s “ABC Art” is highly prized for its treatment of Minimalism’s shift to a new sensibility and its rejection of the emotional content of Abstract Expressionism. Donald Judd’s “Specific Objects” also adds significantly to the material forming a core reference for Minimalism.

Authors of writings on Pop’s ascendancy frequently establish links between America’s growing materialism and the artists’ celebration of society’s icons. Michael Fried notes that “an art like Warhol’s is necessarily parasitic upon the myths of its time, and indirectly therefore upon the machinery of fame and publicity that markets those myths.” Gene Swenson is especially perceptive, too, in “The New American ‘Sign Painters,’ ” and in “Junkdump Fair Surveyed” John Bernard Myers connects money, fashion, vanguard art, and the changing social scene in a way that also relates to the earlier days of the struggling Abstract Expressionists.

Anthologies can be a great convenience. Content here from numerous short-lived midcentury periodicals, including It Is, The Tiger’s Eye, Possibilities, trans/formation, and Black Mountain Review, is impressive, and of course extremely useful due to limited availability. For the most part, this content reflects not only the openness to change that prevailed at the end of World War II, but also the dialogue among members of the Abstract Expressionist generation. In an attempt to accurately capture what was in the air, Mr. Perl is careful to direct attention to all sides in this discourse. Bias becomes historical fact.

Criticism itself became a subject of study in the ’60s, as Mr. Perl reminds us in his introduction. “Art in America 1945-1970” is likely to be regarded as a thoughtful and useful product of this development. It highlights issues, and it demonstrates how insightful writings about the visual arts are contributions to the continuous sorting of America’s cultural history.

Phyllis Braff is an art critic, curator, and retired museum administrator who lives in East Hampton.