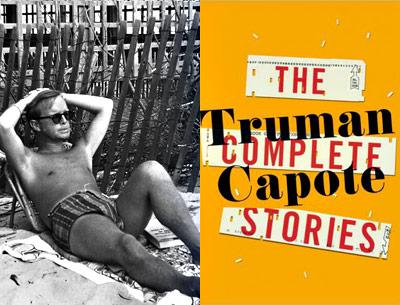

Truman Capote's Identity Games

A republication of the compilation of Truman Capote’s short stories that originally appeared in 2004 has just come out from the Modern Library. The current book, “The Complete Stories,” is only very slightly different from the first publication. But it is a good thing to keep compilations of Capote’s work up to date, in print, on the bookstore shelves, and in library catalogs. It’s important that we are looking after Capote, acknowledging his contribution to American letters as a writer who inhabited many forms.

“The Complete Stories”

Truman Capote

Modern Library, $23

Truman Capote wasn’t prolific, yet he covered a lot of ground by approaching matters through many genres. He excelled as an essayist, novelist, playwright, screenwriter, and short-story writer. Capote was one for the brilliant slim volume (e.g., “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”) and the perfectly economical short form. And so, his writing lends itself to being collected and republished. Additional compilations of Capote’s works include “A Capote Reader,” which offers a wide selection of his output (sketches, novellas, essays, and short fiction), “Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote,” and “Portraits and Observations,” a collection of essays.

To read Capote’s short fiction is to get a real sense of his range in the expression and working out of a central and essential theme: identity. Who am I? What am I? Capote’s points of contact with this theme are various — amusing, chilling, tender, arch, probing.

In several of the stories, fanciness and the pretension to fanciness are examined in brief, clean scenarios. In “The Walls Are Cold,” a rich, beautiful, very young woman savagely shames an unsuspecting sailor in an attempt to mask her own emptiness. In “A Mink of One’s Own” and “The Bargain,” the action revolves around the selling of a mink coat from one woman in desperate need of money to another in desperate need of the substance of self.

Those two stories are very similar, though the buyers of the mink sport different exteriors — different versions of need. The similarity of these two stories seems to signal how precious Capote’s material was to him, how the symbol of the mink coat — the buying and selling of it, the transferable quality of status — held him, compelled him.

Years ago, I received a secondhand copy of Capote’s genre-busting work “In Cold Blood,” which explores and details the murder of a family in Kansas and was termed a “nonfiction novel.” The book was a gift from my friend Jason Engel, a wonderful, mirthful, and discerning reader. He’d inscribed it with a jaunty scrawl: “I hope this never happens to you.”

The same could well be said of a certain category of Capote’s short fiction. The psycho-emotional danger of compromised identity described in a handful of his stories is potent, captivating, scary. The stories I’m talking about are neo-gothic in type; they have a creepy air, a ghost story feel that partakes of tension, of the friction between the real and the fantastic. The stories propose a class of unreality that expresses an interior condition so totally, inextricably real it is at once derailing and clarifying.

As a comparison, think of John Cheever’s well-known short story “The Enormous Radio,” which appeared in The New Yorker in 1947. In it, a couple is exposed to the woes and decrepitudes of the private lives of others in their apartment building when a new radio (sinister in its size and baffling technology) impossibly — supernaturally — broadcasts private conversations into the peace of their living room. That window to the horribleness and hypocrisy of others’ lives brings the horribleness and hypocrisy of the couple’s own lives to light. The sinking feeling at the conclusion of the story is quite desperate.

In Capote’s “ghost” stories he is more focused on the depths of an individual than the individual’s relationship to society. A feeling of sorrowful alarm resounds. Capote engaged with these fictions with total commitment. His apparent empathy around the vulnerability of identity makes for tales that are real at the core.

The standout in this group of five or so stories is “Miriam,” which you don’t want to read alone in the house at night unless your sense of self is ironclad and the skeletons in your interior closet are fully clothed. “Miriam” was first published in Mademoiselle in 1946 and won the O. Henry Award. (I’ll note here that I did not glean this information directly from the book, which contains only copyright dates, not dates or locations of publication for the stories.)

The story revolves around Mrs. H.T. Miller, a “plain and inconspicuous” widow who lives very simply and comfortably by benefit of her late husband’s life insurance policy. “Her interests were narrow, she had no friends to speak of, and she rarely journeyed farther than the corner store.” Mrs. H.T. Miller goes to the movies one night and encounters a little girl called Miriam, which is Mrs. Miller’s given name also. The girl is ghostly, strange, and a bit rude. Next, the girl comes to Mrs. H.T. Miller’s home, uninvited, late in the evening, and out of a snowstorm.

“How did you know where I lived?”

Miriam frowned. “That’s no question at all. What’s your name? What’s mine?”

The girl returns again to Mrs. Miller’s home, with an uptick in her rude behavior. She becomes aggressive, invasive. She remains unexplained. Mrs. H.T. Miller runs for help from a neighbor, who examines the apartment and finds no trace of anybody. Yet when Mrs. H.T. Miller is alone Miriam re-emerges as a threat: “Mrs. Miller stiffened and opened her eyes to a dull, direct stare.”

I hope this never happens to me.

In this story and the others of its ilk Capote shows the clarity of his powers as a revealer of the vulnerability of the self. His aptitude for this is boiled down to the very nut of it in these brief pieces of short fiction, complete in slender glory. His light, witty style acts as a binding agent for the prose.

In the compilation of Capote’s short stories at hand, you’ll not get much new or unavailable elsewhere, but it feels gracious to be offered a current opportunity to consider a writer of such fineness, a constructor of such fragile and true fictions.

Evan Harris is the author of “The Art of Quitting.” She lives in East Hampton.

Truman Capote lived in Sagaponack.