Two Striking Serialists

There is a lot of white space in the work of both Matt Kenny and Adam Marnie, on view at Halsey Mckay gallery in East Hampton. Sometimes it seems the art is an extension of the wall, a way of lying on top of it while gathering its support. In the case of Mr. Marnie, it is the wall, playing with our notions of positive and negative space.

Neither show consists of a lot of work. Upstairs, Mr. Marnie’s four-piece installation was the artist’s reaction to that specific space. The loft in the gallery is small and uneven, with a peculiar eagle’s-nest outpost to look over the downstairs gallery.

Mr. Marnie took the relationships between the walls into account in a show he titled “Recursions.” If we take his title as a mash-up of recurrence and version, we arrive at some idea of what he is getting at.

This installation uses two mediums the artist has employed in other ways. There is the inkjet print and the drywall used as support. Rather than prints of flowers or trompe l’oeil photographs of exposed building supports, here he takes a minimalist approach, but a striking one.

The minimalist paean comes from the monochromatic palette with a reflective, almost metallic, mechanically made sheen. It is also derived from the pseudo-mathematical relationship between the individual parts, alluding to the golden ratio, which ends up subverted. The artist derives his own pattern, going from a single cutout of the first drywall panel to two, then three, and finally six. The pattern’s imperfections echo the oddball shape of the space.

With four different pieces in the installation, each with a different title and its own price, the assemblage touches on post-modern irony as well, setting up the necessary condition that this piece is based on a specific place and time and then effectively saying, forget it, you can buy it separately anyway.

The surface on these pieces is fascinating. Uninitiated viewers might see a flat canvas at first, but it is obvious, closer to the works, that the white space, not pristine, is the gallery wall. They might assume then that the actual architecture of the piece is some kind of framing device, but it is also clear from the cuts that rather than being built up out of nothing, the way a wooden frame might be assembled from parts, these were intact pieces of something else that were carved up just for this purpose.

The precisely incised but sometimes roughly executed cuts, along with the red color, hint at violence, and the less than pristine surface, with smeary fingerprints and mars and scars from the manufacturing process, tarnishes what would have normally been a Minimalist’s clean edges and gleam. These are far more complicated works than they appear.

It might be said that Mr. Kenny’s show in the main gallery is somewhat opposite. His images have more complexity on a superficial level, but it becomes clear that they are also variations on certain themes. Even without the simplicity of Mr. Marnie’s work upstairs, it would soon be obvious that another serialist is on display here.

Mr. Kenny plays with iconic sites and objects such as Google Earth images of McCarran Pool, turning the watery imagery on its side to form new shapes and architectural forms. It’s imperfect and idiosyncratic, with no hinted-at or subverted rationality alluded to. He literally turns it on its head.

His triptych of the 9/11 memorial is more subdued, but manipulates the aerial imagery of the reflecting pool in a way that calls memory into question: how the mind plays on past events or objects to warp them and create new meaning. The same can be said of the act of memorializing and how the memory of those lost may also be altered or co-opted over time by those who may gain from that alteration.

There is also an engaging series of enamel paintings on aluminum, apparently employing a visual pun of a large and powerful staff crushing and then pulverizing two carved blocks of stone. One is inscribed “hours, minutes, seconds.” The other is inscribed “conditioned reflex.” The surface is often slick and shiny, in grays with black and white; the brush sometimes used in a more painterly way to suggest the hand of the artist in the otherwise comic-book illustrative style.

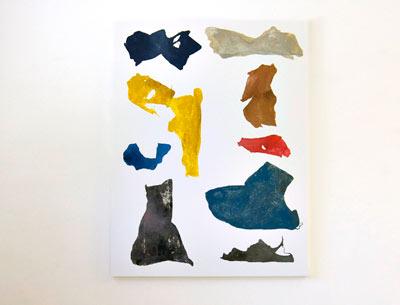

The most striking works come from an unlikely source: black plastic garbage bags. This seemingly low material is inked and run through an etching press. The colors of the printed forms against a smoothly sanded white-painted panel are happily insouciant, balancing off each other the way a third or fourth-generation abstract artist might deconstruct a New York School painting. Yet it is neither analytical nor pedantic, it is surprising, fresh, and free, as if the panel represents the part of the sky where children’s helium balloons, one minute precious, the next a restless renegade, leave their imprint when they go to die.

The shows are on view through Monday.