From Unhappy Beginnings

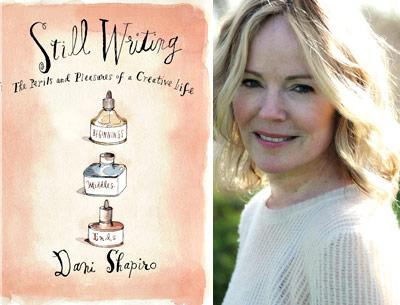

“Still Writing”

Dani Shapiro

Atlantic Monthly Press, $24

The novelist who taught my writing workshop liked to tell us that people who have had happy childhoods start hedge funds or run for Congress — but they don’t become writers. While I wouldn’t put money on that equation, Dani Shapiro, in “Still Writing,” her elegant, inspiring, and practical guide to living the writer’s life, is a vivid illustration of his point.

The traumatic events that jump-started her writing career were the culmination of a lonely childhood as the only offspring of older parents — an obsessive mother and a sad but loving father who found comfort in his Orthodox Jewish faith. Their dysfunctional marriage aroused Ms. Shapiro’s curiosity. What were they talking about behind closed doors? As an adolescent and teenager she began writing to find out.

What might have been a straightforward journey to a literary life was derailed, however. While a student at Sarah Lawrence College she began an affair with the wealthy, seductive (and, she discovered later, criminal) stepfather of her best friend and left school, ostensibly to become an actress but in fact to be his mistress. One night, four years after she’d left college, her father, with her mother alongside him, lost control of the car he was driving. The accident was brutal. Ms. Shapiro’s father lay for several weeks in a coma, regained consciousness briefly, and ultimately died. Her mother suffered innumerable broken bones, particularly in her legs. It took several years before she was back on her feet.

The accident shocked Ms. Shapiro to her core and catapulted her out of the life she’d been living. She wanted to do something to make her beloved father proud. She ended the affair, went back to school, wrote a novel, and graduated from a master’s program in writing at Sarah Lawrence. Her first stop after the ceremony was her father’s grave. She has been writing ever since. Her commitment to a creative life is absolute.

Among the many books that inspire writers with tips on craft and emotional support (“Writing Down the Bones” by Natalie Goldberg, “Bird by Bird” by Ann LaMott), what distinguished “Still Writing” for me was its generosity. Along with dozens of tactics and mind tricks designed to get a writer writing and keep him or her writing (day by day, week by week, year by year), Ms. Shapiro offers a piece of intimate memoir, a meditation, or sometimes an illustrative episode from another writer’s life.

She understands that advice is always useful — but stories are what we remember. I read “Still Writing” as if it were a novel, its voice soft and insistent in my ear. I wanted to know what I was going to find out about Ms. Shapiro and how she kept going.

Not only was she candid about all the obvious ways she has had of preventing herself from writing (road blocks all writers, experienced and novice, will recognize: the internalized voice of the censor, the phone, e-mail, the Internet, wanting a cigarette) and how she overcomes them, but she was equally revelatory about the tough stuff, the facts it’s harder to back away from. Six months into his life her infant son was diagnosed with a rare disease with a small probability of survival. She knew, she tells us, “that if he wasn’t okay . . . my life would be over. I believed that the loss of a child would be the only pain from which it would be impossible to recover.”

The ways she normally had of detaching from an experience in order to write about it wouldn’t work here. How could writing save her son? She quotes John Banville — a quote that has stayed with me. In writing about Joan Didion’s “Blue Nights,” a book about the loss of her only daughter, he says, “Against life’s worst onslaughts nothing avails, not even art, especially not art.”

Ms. Shapiro’s son does survive. She catalogs his illness, along with her parents’ accident, as one of the markers that divided her life into a before and after, a place on a continuum that left her irrevocably altered. “It was written on my body. My instrument had changed.” It took a year and a half of staring at the wall of her studio, she tells us, but eventually she began writing again, a book about maternal anxiety.

Though Ms. Shapiro’s childhood was not a happy one, it was a structured one. Her family observed the Sabbath. She practiced the piano. And because of her mother’s obsessiveness she grew up in a spotless house with color-coordinated drawers. In many of the methods she recommends for overcoming writer’s inertia, self-loathing, bad days, blank pages, Monday mornings, beginnings, middles, ends, there is a powerful streak of stick-to-itiveness, a determination not to be defeated that I found bracing and which I suspect harks back to discipline early learned. (Before writing she makes her bed.)

She recommends yoga and meditation for focus. She tells us she works five days a week, regularly, entering her studio right after her son leaves for school. When she is working on a book she routinely writes three pages every weekday morning and revisits them in the afternoon. She believes in rhythm and habit, in making a promise to herself and keeping it.

She understands, however, that no matter how firm your commitment, life will find a way of distracting you. “A school play.” “A friend in crisis.” What William Styron called “the fleas of life,” she tells us. She warns that once interrupted it will be hard to return to your pattern, but with determination, you can.

She commiserates about uncertainty and risk — creative and financial. No one will like what we’re writing. No one will buy it. “We [Ms. Shapiro and her husband, also a writer] are always one potential disaster away from . . . well, potential disaster. A health crisis. A tree falling on the roof. A disability. What then?” But, she tells us, she and her husband have as recompense the fact that they are doing what they love, doing what they must. “This life chooses us.”

“Still Writing” is a wise book, illuminated by honesty and the passion Ms. Shapiro obviously feels for her subject and the life she’s chosen. I left it feeling in the mood to write and promising myself that I’d follow her ardent ruling to stay away from the Internet. The novelist who taught my workshop never assigned books about writing but advised that writers learned to write by writing, a conundrum with which, Ms. Shapiro tells us in the pages of her inspiring book, she agrees.

Phyllis Raphael, the author of “Off the King’s Road,” has taught in the writing programs at Columbia, New York University, the New School, and a longstanding private workshop that she founded in Manhattan. She lives in New York and Amagansett.

Dani Shapiro is a former Sag Harbor resident.