Varieties of Jewish Experience

It’s what we have in common that makes us unique.

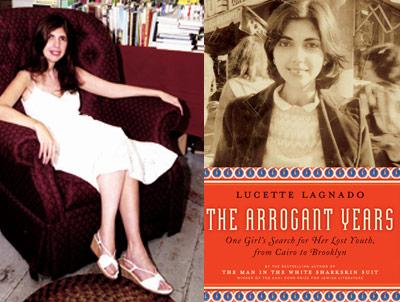

I’m not sure whether that’s a quote from somebody or my own thoughts as I read “The Arrogant Years: One Girl’s Search for Her Lost Youth, From Cairo to Brooklyn” by Lucette Lagnado.

Beginning with a vivid reconstruction of life in prewar Cairo, the story unfolds against a background of international events: Egypt at war with Israel, France, and Britain over the Suez Canal, Nasser taking control of Egypt, scattering the once-vibrant Jewish community, including the Lagnado family, forcing them to replant themselves in America. Critics have praised “The Arrogant Years” for its story of courage and ambition that animated mother and daughter, Edith and Lucette, to find a way through their confusing, unwelcoming new country, despite the ravages visited on the family by “the evil eye.”

A child myself of Jewish refugees, for me “The Arrogant Years" is an ancient Jewish refugee story — the flight from Egypt — but also a contemporary one spreading daily through Asia, Africa, and Europe, a local story of globalization, politics, and climate change contained in the universal story of deracination, dispossession, and exile. Our families’ stories — Lucette Lagnado’s and mine — are two of the varieties of Jewish experience.

“The Arrogant Years”

Lucette Lagnado

Ecco, $25.99

Three themes shape the Lagnado story: The first, the “arrogant years” of the title, refers to that time in a young person’s life when she stands at the peak of her powers. Lucette’s arrogant years were cruelly shortened by catastrophic illness. Her father, Leon’s, arrogant years were spent as a Cairene boulevardier, jaunty in the white sharkskin suit he never wore again after leaving Egypt. Edith knew her arrogant years in Cairo, as librarian of the magnificent pasha’s library, a life she somewhat recaptured in the Brooklyn Public Library’s catalog department.

With Leon diminished by illness and more absent than present, the Lagnado family functioned without a man, as before her marriage Edith and her mother, Alexandra, had lived in Cairo without father and husband.

It’s been much told, this refugee story of sic transit gloria mundi, of how are the mighty fallen! My Jewish parents, two newly minted doctors, fled Hitler’s Europe in 1937, setting sail for India, where a six-year spell in British-Indian internment camps terminated their arrogant years. Unfamiliar with the evil eye, my father interpreted his misfortunes as spiritual tests. Sometimes, arrogant years return: Released from internment, my parents rebuilt their medical practice in Lahore among the welcoming Muslims of Pakistan. While the Lagnado family suffered neglect and maltreatment at the hands of Egyptian and American doctors, in my story my parents were the doctors. It was their good fortune to land in a place where physicians were greatly valued, where being European mattered and being Jewish didn’t.

Rebuilding the hearth is the book’s second theme and the anthem with which Edith urges Lucette to pull together their fragmenting family. But in truth, how much Lagnado hearth was there? More man about town than homebody, Leon’s Cairo habitat was defined by Judaism and Arabic, while his wife, Edith, was defined by all things French.

Arriving in America, Lucette’s older siblings detached from their immigrant home to seek a place in secular, capacious America. Lucette gives us only a sketchy glimpse inside the family’s Brooklyn home, as if she was never fully there. Instead, we follow mother and daughter bonded in a world unto themselves as, holding hands, they dart all over New York, restless and uprooted, sharing a hearth of books, libraries, and schools. Deeply ambitious for her daughter, Edith is shattered when the French lycée in Manhattan rejects Lucette’s application.

Similarly driven to educate their children, my parents sent us to faraway boarding schools into cultures that were neither theirs nor ever entirely ours. Whether we wanted it or not, we became independent. The Lagnados resisted unpacking their Egyptian suitcases, leaving Cairo inside them, time-warped and intact. Growing up, I was forever packing and unpacking suitcases, shuffling from one temporary address to another. Our hearth was portable and virtual, its bricks and mortar constructed from letters, airline tickets, a network of friends, relatives, and strangers, held together by my parents’ stubborn vigilance. Perhaps a hearth means the most when the years are their least arrogant — as our parents approach the end of their lives. I know the sorrow at the heart of Lucette’s story.

Separation is the third theme of “The Arrogant Years,” symbolized by the carved wooden divider, the mechitza, that separates the sexes in conservative Jewish synagogues. For Lucette the child, the divider was a provocation, a barrier for her to dismantle, ending the separation. My mind goes to the massive wall the Israelis have built to separate themselves from the Palestinians and the Palestinians from their lands and one another, and I realize that separation lies at the core of every refugee family — it is part and parcel of the broken hearth, dividing and blocking the flow of continuity.

Beyond the synagogue’s wooden barrier, separation runs throughout Lucette’s life: between affluent and poor Jewish neighbors in Brooklyn, between Ashkenazi and Sephardic synagogues, public and private schools, the separation from her siblings, between her and the other Vassar girls, the separation between her parents’ French and Arab cultures. In a nursing home at the end of their lives, her parents sit side by side in wheelchairs, not speaking to each other. Years later, Lucette visits her former synagogue, shuttered now, the divider merely a pile of sticks. With the barrier gone, she feels a loss of security and identity: She understands that the mechitza did more than separate men and women worshipers. Released from the barbed wired of the internment camps, my father, suddenly too free, was afraid.

Two among millions of Jewish refugee families — it’s what the Lagnado family and mine have in common that makes us unique.

—

Lucette Lagnado is a reporter for The Wall Street Journal. She has a house in Sag Harbor.

Hazel Kahan is writing a memoir about growing up Jewish in Pakistan. She lives in Mattituck.