A Vessel ‘So Remarkable’

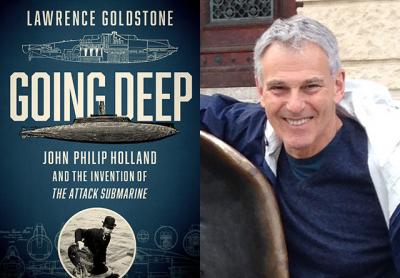

“Going Deep”

Lawrence Goldstone

Pegasus Books, $27.95

On Aug. 26, 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt traveled a short distance from his summer home at Sagamore Hill on Long Island’s north shore to where the submarine the Plunger was docked near Oyster Bay. The boat had been scheduled for a presidential inspection to determine if submarines should be added to the American naval fleet.

But Roosevelt was never one to stand on the sidelines. Rather than observing the submarine’s maneuvers from shore, the president boarded the Plunger to experience it firsthand. After a series of dives, including one that remained underwater for nearly an hour, Roosevelt returned to land a believer. “I have never seen anything quite so remarkable,” the president enthused of his ride.

Given the president’s endorsement, the Navy immediately made contracts for the construction of four new submarines, vessels that would greatly transform the nation’s naval capabilities and the shape of warfare in the 20th century.

That scene on Long Island Sound comes near the end of Lawrence Goldstone’s new book, “Going Deep: John Philip Holland and the Invention of the Attack Submarine.” Mr. Goldstone, the author of previous works on Henry Ford and the Wright brothers, intends his book to rescue Holland, whom he calls “the father of the modern submarine,” from relative obscurity and place him alongside those other more well-known American inventors. His thorough and deeply researched book accomplishes exactly that, but it also tells the far larger history of the submarine’s long and difficult journey to reality.

The idea of underwater boats had been around since as early as the 16th century, when the mathematician William Bourne introduced the notion in his 1578 work “Inventions or Devices.” Other inventors and engineers would envision their own versions of underwater vessels, but it was Jules Verne’s 1869 classic, “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,” that seemed to turn everyone’s attention to the possibility of underwater travel. Yet for all that interest, building a successful submarine proved enormously challenging.

Holland’s genius and near-obsessive dedication to perfecting a working submarine took more than three decades, and he faced nearly as many personal as he did technical setbacks along the way. Born in Ireland, Holland had come to the States in 1872, going to work as a schoolteacher and choirmaster in New Jersey. Submarines, however, were his passion, and he taught himself everything he needed to know for their design.

Remarkably, from the very start Holland’s models showed the two great contributions that he would make to submarine technology. The first was establishing positive buoyancy that allowed for a submerged boat to float to the surface rather than sink to the bottom should the engine become disabled, a critical function for any crew on board. For this design, Holland had drawn his inspiration from the porpoise, much as flight engineers had looked to birds to guide their work. The design involved positioning diving planes near the front of the submarine that could be turned downward, allowing water to flow over them and the vessel to dip below the surface like a sea mammal.

Second, Holland understood that the submarine had to maintain a fixed center of gravity to guarantee its stability. Any change in weight distribution in the craft, including from the firing of a weapon, would shift the center. To offset any changes, Holland devised a series of “trimming tanks” that took on or released weight to keep the submarine balanced as it cruised below water.

All along the way, Holland battled skeptics who criticized his designs while he struggled to finance the costly work of testing and construction. Holland’s rivalry with Simon Lake, a mechanical engineer who built a series of Argonaut submarines and then the Protector, spurred him to perfect his own designs faster. Time and again, Holland won congressional design competitions over Lake, but Lake threw up roadblocks for Holland by protesting the contests as unfair.

And Congress seemed all too happy to oblige with stalling innovation, imposing regulatory burdens, and withholding funding. (This is not the book to read this summer if you are looking for a story to renew your faith in the United States Congress, but it would be a particularly welcome Father’s Day gift for fans of the history of technology or the military.)

Soon Holland could self-finance no more. In desperation, he turned to Isaac Rice, the wealthy chairman of the Electric Storage Battery Company. Rice provided the necessary funding, but his investment came at a steep price, requiring Holland to hand over all his patents along with control of the company. That arrangement foreshadowed Holland’s eventual exclusion from the world of submarining. By the time of President Roosevelt’s 1905 ride on the Plunger, Holland had been driven out of his own company and barred by aggressive litigation from taking up any new submarine work. He died of pneumonia in July 1914 just as World War I was beginning, a conflict that would be marked by the presence of submarine warfare.

Holland would never know about that, or the significant advances made in submarine technology through the 20th century. But Mr. Goldstone’s book rightly places him at the center of that history. As Mr. Goldstone writes in the book’s conclusion, modern submarines “all sail in the spirit of John Holland.”

Neil J. Young is the author of “We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics.” He lives in East Hampton.

Lawrence Goldstone lives in Sagaponack.