Vincent Longo: Squaring the Circle

Vincent Longo had his first exhibition in New York in 1949. Since then his paintings and prints have been shown extensively and joined the collections of dozens of important museums here and abroad. During that time, from Abstract Expressionism through Pop, Minimal, Conceptual, and many other kinds of art, his work has remained resolutely his own. Not static, but driven by beliefs and principles that have informed his practice from the beginning.

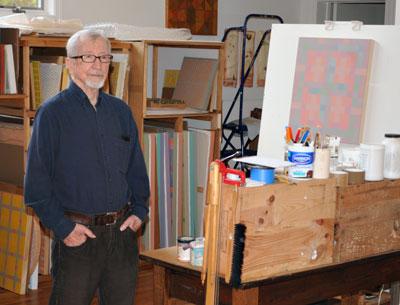

During an afternoon in his sunny studio on Windmill Lane in Amagansett, surrounded by paintings and prints from the 1940s to the present, Mr. Longo spoke authoritatively and insightfully about his work and life as an artist, and the experiences that have influenced his development.

Given his Dickensian childhood, a life as an artist was not an obvious path to follow. Born in Manhattan in 1923, Mr. Longo was orphaned two years later. He and his brother, Frank, were sent to St. Agatha’s Home for Children in Rockland County. “Frank and I were orphans, but most of the kids were not. They were either from very poor families or broken families.” The property was fenced in, and trips to the world outside were rare.

When his mother was dying, her cousin Rose promised to take care of the boys. When Mr. Longo was 14, he and Frank went to live with Rose and her “big, noisy family” in Brooklyn. He attended Textile High School in Manhattan, where he studied commercial art. “But my last year of high school I discovered I didn’t have any talent for it.”

At the time, he met Edmond Casarella, an older boy from the Brooklyn neighborhood who was attending Cooper Union. “He saw that I was interested in art and started giving me drawing lessons. He became a mentor, and I followed him to Cooper.” Though Mr. Longo enrolled as a commercial art major, he changed to painting after one year.

One of his teachers encouraged him in the direction of abstraction and gave him lessons in Cubism. Another, Leo Katz, talked about Cubism as a breaking up of the solidity of objects into planes — the Cubist grid — and introduced the young artist to Jung, Lao-Tzu, and Buddhism.

While at Cooper Union, he had a small cold-water flat he used as a studio. When, several years later, he lost that and found himself with no place to work, Augustus Peck, the director of the Brooklyn Museum Art School, let him enroll for free and use its studio space. While there he took courses with Max Beckmann and Ben Shahn.

Picasso and Kandinsky influenced his work from this period. He showed a visitor an abstract painting from 1951 titled “Green Light” that, while not resembling his more mature work, already exhibited his propensity toward line. Sharp triangles radiate from the center, suggestive of an exploding star. Such “bursting centers,” as he called them, have figured in his work ever since.

During the 1950s he was part of the New York School, but his work from that period doesn’t resemble that of his peers. While he frequented the bars and galleries of the time, he didn’t become a member of the Club, an Eighth Street meeting place for artists of the period, until 1954. “I was so pure about my work I didn’t want to be influenced, so I avoided the Club for six years. What people don’t realize now is that New York was wide open at the time. All the Club members painted differently. The thing they had in common was the desire to break from Paris.”

Mr. Longo said that the most accessible of the better-known artists was Franz Kline, who enjoyed talking with younger artists. “The 1950s and 1960s was the best time to be a young painter,” he said.

In 1957, he learned about an opening at Bennington College in the print shop. He thought it was for one year, but he stayed for 10. The faculty included such Color Field painters as Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Paul Feeley, who was the department’s director. In addition, Clement Greenberg, one of the most influential critics of the mid-20th century, lectured there.

Mr. Longo had been reading Greenberg’s articles in Partisan Review since 1947, and he first met him 10 years later, when they were in a drawing show together. “He was a frustrated artist. He considered himself a failed painter. I was never part of his group. He didn’t like my work, but he liked me. He used to tell people I was the only artist he would run into in libraries.” Mr. Longo also became very friendly with the sculptor Tony Smith while at Bennington, and the two later taught at Hunter College.

Mr. Longo and his first wife, Pat, became interested in Neolithic art in the 1950s and visited various sites in France in 1956. “The idea of an enclosed center, leaving a trace that had some kind of significance, that wasn’t figural, became very developed in Neolithic art,” he said. A 1962 trip to Malta to see the proto-European megalithic temples further reinforced his conviction that abstraction was rooted in ornament, spiral forms, and concentric repetition.

“When I came back from Malta I started doing these dark etchings that emphasized the center. I had been doing really large woodcuts that got a lot of attention, and my etchings got around a lot.” There is a polarity in his work between expressionist gesture and central balance. “I kept the gestural going in the woodcuts. Because the medium was meant for carving, it’s naturally gestural. But whichever way I’m working, woodcuts or paintings, I never plan anything.”

The square and the circle are fundamental elements of his work. “I start with a certain kind of structure, the center relating to the edge at the same time.” The Buddhist mandala and Hindu yantra have been recurring motifs in his paintings, less for their symbolism than for their simple renewal of archetypal forms, “which I thought had a bearing on contemporary discourse.”

“Squaring,” an etching from 1967, consists of four arcs, separated by white space, that describe a circle. No straight lines are used, but when one focuses on the center, the white of the paper emerges as a perfect square.

While his grid paintings might at first seem anything but unplanned, he has written, “The forms and constructs I use are necessarily deliberate, but I work with them relatively freely. Images and ideas are worked out rather than thought out. I hope to come upon something unfamiliar using common forms, repeating them and at times finding some aspect of myself hitherto unrecognized in them. Basic forms such as the grid are taken as given.”

For many years, Mr. Longo avoided East Hampton because it was an “artist’s hangout.” He first visited in 1971 with Kate Davis, an artist he had just started seeing, and fell in love with the area. He and Ms. Davis have been together ever since, renting a house and studio on Copeces Lane in Springs every summer until, in 1988, they bought their current house in Amagansett.

At 91, he still works every day. “I feel that making art has to do with leaving traces. That’s what human life is about, leaving a trace of yourself.”

Mr. Longo’s work will be included in the winter salon at the Drawing Room in East Hampton, where he will have a one-person show in 2015.