The Virtues of Brevity

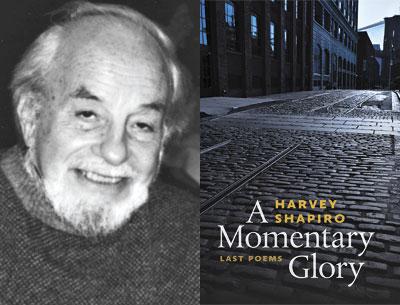

“A Momentary Glory: Last Poems”

Harvey Shapiro

Wesleyan University Press, $24.95

Many years ago, Allen Planz said at one of his poetry readings at Canio’s Books that short poems were the most difficult to write. Too many poets, he said, seemed incapable of the compression and concision necessary to achieve success with short poems. Harvey Shapiro, apparently, has experienced no such trouble.

In “A Momentary Glory: Last Poems,” published by Wesleyan University Press and edited by Shapiro’s literary executor, Norman Finkelstein, readers will notice the dexterity with which Shapiro shapes his short poems in this terrific collection of posthumous gleanings.

Most of these poems occupy a single page in this volume. Most of these poems are shorter than sonnets. Some of the longer poems, such as “Departures,” “Lines (3),” and “City Poem,” seem stitched together from shorter, fragmentary pieces that may have worked just as well individually.

These poems are so short that readers may wonder how they succeed at all. Shapiro’s poems eschew ornamentation. They lack, for the most part, figurative language. Robert Frost wrote that “Sound is the gold in the ore,” but readers will find none of that gold here. And, unlike that famous short poetic form haiku, Shapiro’s poems don’t focus on nature, per se, and they don’t march to a syllabic beat.

In fact, it may seem to readers that Shapiro has taken a monkish vow forswearing tropes, assonance, symbols, and objective correlatives, all the poetic armor of the ivory tower. Shapiro’s poems represent a refutation of Eliot’s high-minded rhetoric, of Stevens’s musical surrealism, of Frost’s insistence on traditional forms.

This is not to say, however, that Shapiro’s poems lack fundamental poetic qualities. On the contrary, what these poems evince is often missing from contemporary poetry — simple diction, clarity, and honesty.

“A Momentary Glory” makes clear Harvey Shapiro’s long affiliation with the Objectivist poets, whom he names in more than a few of these last poems. According to the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, Objectivism grew out of the imagism of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams and insists upon the use of the concrete for its inherent sensuousness and properties of individuality and uniqueness.

Shapiro makes no secret about his poetics. Many of the poems here concern poetry and Shapiro’s aesthetic position. For instance, “Poetics” makes clear Shapiro’s penchant for clarity:

In the argument over rhetoric

I am always for the lofty

but somehow wind up opting for the low.

Is that because Rezi speaks in me still

his Jewish moral concerns

which he wanted set down lucidly,

matter-of-factly,

with the lucidity, never prettiness

of Du Fu and Li Po.

“Rezi,” of course, is Charles Reznikoff, a leading Objectivist poet whose career spanned most of the first two-thirds of the 20th century, and who greatly influenced Shapiro’s work. Other Objectivists to whom Shapiro gives a shout-out in this collection include George Oppen, Louis Zukofsky, and Carl Rakosi. The allusion to Du Fu and Li Po is a nod to the pellucidity of Chinese poetry, to the virtues of brevity, compression, and clarity, tenets also of Objectivism.

Poetics aside, Shapiro’s poems also fascinate with quick cuts and juxtapositions. In “The People’s Poet,” for example, each of the poem’s four lines surprises because of their relationship to one another:

He was so pleased

with the poverty of his imagination.

It made him

brother to everyone.

One can’t quite imagine a poet pleased with an impoverished imagination, but here that very lack is an equalizer. This poem registers a profound recognition of poetry’s audience, that the dearth of, say, figurative language represents a democratization of poetry. The very prosaic qualities found in the Objectivists, including these last poems from Harvey Shapiro, close rather than widen the distance between poet and reader, suggesting that accessibility may be poetry’s finest virtue.

Other poems here work in this same brief and jarring manner. “The Old Jew,” “Nightpiece,” “Suburban Note,” and “George Oppen” spring an unexpected epiphany in the context of a few, otherwise innocuous, lines. Many of Shapiro’s poems hardly begin before they startle.

Shapiro achieves this with whatever subject is at hand. He writes about poets and poetry, World War II and his time in the service, aging and mortality, Jewishness, and memories of youthfulness and eroticism. This collection validates Shapiro’s reputation as an “earthy” poet, as in the first four lines of the book’s first poem, “The Old Man Has One Thought and Then Another”:

Let’s go out

And fart in the sunlight.

Let’s go to the playground

And check out the young mothers.

Or as in “Cynthia,” reprinted here in its entirety:

Reach in, she said,

and get some juice.

That was happiness.

For all this collection’s charms, readers may find some of the poems too brief and fragmentary. Some poems lack the quick epiphany or jarring juxtaposition that make the best poems here work. One example of just such a poem is “Florida”: “The sea beating / against the parking lots.”

A few other poems like this, mere postcards, appear here and there, but this book is worth a reader’s time and money. Don’t let the fact that this volume can be read — twice — in a couple of hours delude you into thinking you can write poems, too; Shapiro’s breezy offhandedness is the result of a lifetime of writing poems and of learning what to include and what to leave out, a skill few young poets today, no matter their aesthetic affiliations, seem to possess.

Harvey Shapiro’s poems, for the most part, attract and hold a reader’s attention because he has chiseled them down to their bare essentials, and each of the best shines radiantly, a momentary glory.

Dan Giancola is a professor of English at Suffolk Community College. His collections of poems include “Part Mirth, Part Murder” and “Data Error.”

The poetry of Harvey Shapiro, who divided his time between Brooklyn and East Hampton and died in January 2013 at the age of 88, will be celebrated with a group reading at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor on Saturday at 5 p.m.