The Wages of Adoption

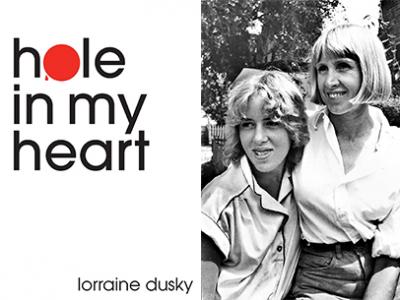

“Hole in My Heart”

Lorraine Dusky

Leto Media, $11.98

In 1979, Lorraine Dusky, a journalist, published “Birthmark,” a memoir about relinquishing a child — her daughter — to adoption. The book detailed Ms. Dusky’s sense of loss, gave voice to a perspective not yet widely heard, and established Ms. Dusky’s role as a writer of adoption literature and figure in the adoption reform movement.

Her current memoir, “Hole in My Heart,” recaps some of the material from the earlier volume and then takes up the story of her search for her daughter 15 years after the child’s birth. The book is an exploration of the complexities, pitfalls, revelations, and power of Ms. Dusky’s relationship with her daughter, Jane, through Jane’s suicide at age 42. In some ways, the two volumes together offer a cultural history of adoption in America, from the 1960s to 1990s. Ultimately, “Hole in My Heart” sketches out the wages of adoption from Ms. Dusky’s strongly held perspective.

Ms. Dusky is particularly lucid in outlining the ways in which, for her, relinquishing her child was not truly a choice, but an action in the absence of real alternatives. In 1966, when she was pregnant, abortion was a remote option that did not materialize for her, and her resources — psycho/emotional and otherwise — were nil. She fully addresses the “Who do you think you are?” stance toward mothers (language is sensitive and tricky here; birth mother, biological mother, first mother, natural mother? — an understanding of who’s who gained through context is perhaps the best course to steer in general) who wish to search for children they gave birth to, or offer themselves for further contact.

That is, she identifies herself as a person who did not feel she had a choice. Yet, somehow, she does not rationalize: “The right thing would have been to keep her. I did what I did, and I have had to live with the consequences. The justifications might repeat in my brain — it was the times, it was the shame of it all, I was alone without anyone to turn to — but none of it reaches that damn hole in my heart.” Fifteen years later, Ms. Dusky expresses a sense of renewed opportunity in the choice of searching or not searching for her daughter, offering contact or not offering contact.

The reader will find that Ms. Dusky communicates a driving need to give her child the opportunity to know her and to have an understanding of her genetic roots. She feels, categorically, that children have a right to know their biological origins and that parents as well as the state have a responsibility to make that information available. This was not the case with closed adoptions, where the original records of births were sealed and inaccessible.

Ms. Dusky is thorough in her discussion of this as a historical phenomenon that she feels has not altogether vanished, lingering in less-than-open adoptions.

And she is impassioned, likening closed adoptions to the condition of slavery: “Other than slavery, there is no instance in which a contract made among adults over another individual binds him once he becomes an adult. It takes from him full autonomy as a free person; it makes him subject to the whims and preferences of another, and it does so indefinitely and for all time. Anything other than full autonomy — which surely includes the right to know who one was at birth — is wrong morally, wrong legally, wrong any way it can be interpreted.”

Although the book, arising from Ms. Dusky’s perspective and need to tell the story, is largely focused on her own experience and expressive of her own personality, a portrait of her daughter, Jane, emerges as well. Jane lived with epilepsy that onset at age 5, was learning disabled, and suffered from depression as well as low self-esteem, stemming from many factors, and PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder). She was deeply troubled.

Ms. Dusky is careful, respectful, and loving in her treatment of Jane — yet there is more than a hint that her daughter was a drama queen and manipulator with an uneasy relationship to the truth: someone not always easy to love, or accepting of love. It is clear, also, that Ms. Dusky loved Jane abidingly, taking delight in the physical similarities between herself and her daughter, and in the biological imperative that seemed to bind them, often expressed in similar tastes and through fashion.

The notion of being bound by genetics is of great importance to Ms. Dusky, and she finds evidence in abundance that may not always seem significant to the reader. It is perhaps impossible to fully comprehend the fabric of any person’s bond with another. However, Ms. Dusky falls short of making a case for the ties that truly bind being necessarily genetic in nature.

"Hole in My Heart” is compact, readable. Ms. Dusky’s writing is both catchy and absorbing. Although her enthusiasm for detail sometimes runs to the extraneous, she turns a phrase extremely well. She summons her command of the language and adds a healthy dose of humor to corral her emotion around the issues into a cogent, well-paced narrative. A journalist with an excellent sense of story, she plumbs the depths of her investment in this material. Readers will be carried along.

The book’s mission, however, is not to simply tell this story or even more broadly to preserve a personal and also historic record. “Facts & Commentary” sections are interspersed to punctuate the second half of the narrative and act as mini opinion pieces, serving to highlight and extend the ideas about adoption Ms. Dusky explores throughout the book. Here the reader is asked to face the volume quite baldly as a polemic against adoption, particularly but not exclusively closed adoption. Ms. Dusky writes, “Open adoption is a step forward, but it is not a panacea for the myriad issues that stem from relinquishing a child to someone he or she does not have a strong genetic connection to.”

Ms. Dusky’s perspective is specific and strongly stated. It will be embraced by some, with the power to clarify and comfort, and it will be rejected bitterly by others, with the power to undermine and rankle.

The parent/child bond remains mysterious and miraculous.

Evan Harris is the author of “The Art of Quitting.” She lives in East Hampton with her husband and two sons.

Lorraine Dusky lives in Sag Harbor.