A Walk Through the Wild Side

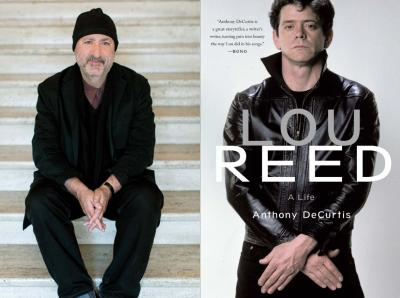

“Lou Reed: A Life”

Anthony DeCurtis

Little, Brown, $35

In the veteran rock journalist Anthony DeCurtis’s new biography, “Lou Reed: A Life,” John Cale expounds on his Velvet Underground bandmate’s songwriting: “Lou comes to terms with himself in songs. It’s like somebody discovering their identity.”

Mr. DeCurtis runs with that notion by taking a chronological tack through Reed’s colorful life, shedding light on his personal trials by way of a series of poignant interviews with those closest to him and pointing out how these events informed and sometimes made it directly into his work. This makes for a comprehensive yet intimate portrait of a driven man inseparable from his art, who when it was all said and done became widely considered one of the greatest singing poets of the last century. Not bad for a wiseass kid from Freeport, Long Island, who did a hell of a lot of talk-singing.

One thing I loved about this book was that we get the Lou Reed origin story. The raw materials were clearly there from the beginning: the inherent “f-you” attitude and irreverent urge to shock whomever he considered representative of the status quo, his natural affinity for cutting-edge counterculture writers like Allen Ginsberg and Hubert Selby Jr., his love of free-form jazz. These all point to a young guy cocked and loaded for bear, but along with those influences are a few profound incidents and people who entered his life and truly shaped him.

The first was his undergoing electroshock therapy when he was just 17. In the fall of his freshman year at New York University Reed started exhibiting bizarre, schizophrenic-type behavior along with bouts of depression. Not knowing what to do, his parents were talked into this newfangled treatment in the hope of snapping him out of it, a common practice at the time. One with an imagination fueled by comic books might locate this as Lou’s “zapped by gamma rays, turned into the Hulk” moment, but I believe that to be a stretch. We do find out, however, that once on the other side of these shock treatments his mood darkened considerably, and his relationship with his parents was damaged irreparably.

Later in the book, when discussing the Reed song “Magic and Loss: The Summation,” the closing track on the album “Magic and Loss,” Mr. DeCurtis astutely points out that in it Reed uses the imagery of passing through fire as a form of purification, writing, “as if the flames of all the struggles one faces in life were a kiln in which one forged one’s perfection.” The irony of the earlier electroshock certainly springs to mind with this allusion to emotional and spiritual alchemy.

Once functional and recovered from the electroshock (and mysteriously nothing resembling this kind of mental illness returned), Reed transferred from N.Y.U. to Syracuse University, where he met the almost famous poet Delmore Schwartz, his writing teacher. It was through Schwartz’s encouragement, influence, and tutelage that Lewis Reed blossomed into Lou Reed.

He also met a young beauty named Shelley Albin, who became his first love and would be the muse for many early Reed compositions with the Velvet Underground, including the classic “Pale Blue Eyes.” He’d write arguably his most mercurial anthem, “Heroin,” while at Syracuse, and he hadn’t even tried it yet.

The interviews with Ms. Albin were some of my favorite parts of the book, recalling the young Lou, full of artistic energy, at times a cocksure egotist, at others fraught with insecurities. She and the others interviewed really give unabated, forthcoming accounts of their relationships with Reed.

I got the feeling that Mr. DeCurtis couldn’t have mined such personal terrain had Lou still been alive, but he sensed gold in them thar hills, and gold is what he got. All the subjects seem eager to tell their side, and none, even the ones who might’ve had cause, ground an ax.

After Syracuse, that’s when the book starts its thrill ride. The Velvet Underground forms and the Factory years begin, and with them, of course, Reed’s much ballyhooed collaboration with artist, Factory founder, quasi-mentor, and ubiquitous to all things 1960s New York Andy Warhol. From there it’s on to his ’70s post-Velvet Underground solo career, when he finds success with the David Bowie and Mick Ronson-produced album “Transformer” (featuring the song “Walk on the Wild Side”).

On through the decades Mr. DeCurtis takes us, charting Lou Reed’s life and career, year to year, wife to girlfriend to live-in tranny lover to another wife (he’s almost never single), to being out of control on booze and speed to getting sober, to becoming a practitioner of tai chi. Mr. DeCurtis was the perfect author to write this book, and as a fan of Lou’s I’m very grateful he did. He goes to painstaking lengths to examine each record Reed made, thoroughly measuring its impact on rock ’n’ roll at the time, then weighing its significance now and up against the rest of his body of work — almost all, save for a precious few, were commercial flops.

Lou Reed died in 2013 with $30 million in the bank. Oh to be that kind of failure . . .

Lou Reed lived part time in Springs.

Christopher John Campion, a singer-songwriter and regular visitor to Amagansett, is the author of “Escape From Bellevue: A Dive Bar Odyssey,” published by Penguin-Gotham.