When the Worst Happens

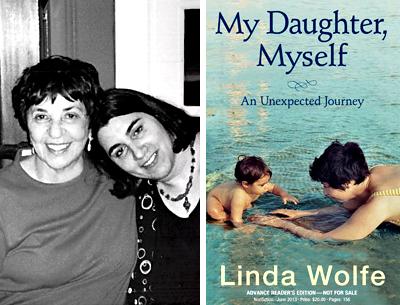

“My Daughter, Myself”

Linda Wolfe

Greenpoint Press, $20

On a Mother’s Day visit to Texas to see her only daughter, Jessica, mother of two small children, a mother’s worst nightmare begins. Suffering from dizziness and a splitting headache, Jessica is rushed to the emergency room. A CT scan and “every test known to women” are given and Jessica is sent home, diagnosed with a migraine.

When Jessica calls from the E.R. to tell her mother she’s okay, Linda goes down on her knees, not praying, but wiping up eggs she had spilled in nervous and frantic anticipation of what she might learn when she picked up the phone.

A day later, however, Jessica is not improving, and after another trip to the E.R., Linda discovers that her daughter had a massive clot in her brain and had suffered a stroke. It turns out that some 800,000 Americans a year are assaulted by stroke, killing about 17 percent and damaging the lives of many who survive. The primary victims of stroke are over 65, and only 10 to 15 percent are like Jessica, who was 38 at the time.

A searing account of a daughter’s physical and mental rehabilitation, “My Daughter, Myself” reminds us of the fragility of life and the powerful, primal cord that binds a mother to her daughter. Journalist, essayist, and contributing editor to New York magazine, Linda Wolfe charts her experience, and the dizzying foreign maze of dealing with hospitals and doctors and illness, with a reporter’s unsparing attention to detail.

We discover that if the surgeons went in to relieve the swelling in Jessica’s brain, she’d most likely bleed to death. Although Jessica experienced occasional periods of lucidity, she could no longer perceive anything on her left side, “as if half of her had vanished.” Linda and her son-in-law, Jon, are told by the surgeons that Jessica’s chances of survival are slim, and even if she survives she’s likely to be paralyzed and suffer severe neurological damage. Expecting the worst, Jon begins to think about the time he would need to get his family to Texas for Jessica’s funeral.

Compelling, heartbreaking, and down-to-earth, Ms. Wolfe reports the hours of agony she and her son-in-law shared as Jessica eventually undergoes high-risk surgery, remains comatose, and doctors offer little hope. To console and give ballast, Ms. Wolfe quotes Maimonides on what constitutes “death,” the time when one can stop all heroic measures — and also from Joan Didion, Michel de Montaigne, and John Donne, all of whom wrote profoundly and eloquently about illness, death, and the loss of a child.

Divided in two parts, “The Nightmare” and “The Long Road Back,” and with a title that echoes a classic feminist work about the ties that bind mothers and daughters, Nancy Friday’s “My Mother, Myself,” this memoir allows the reader to experience a mother’s intense, unswerving fear and helplessness, and also her abiding love and devotion. The best parts are where we are offered a glimpse into the anxious psyche of a mother who prays every night that her gifted daughter won’t end up in a nursing home, and universal insights and truths about motherhood and a mother’s inability to take away a daughter’s pain.

“I knew it was good that she was expressing her feelings,” Ms. Wolfe writes, when her daughter begins to slowly recover, “but I was distraught at hearing them and being unable to make things better. Facile encouragements wouldn’t do. Nor would denial. What to do? I just let her talk, let her tell me things I longed not to hear because they made me feel so inadequate but which she now urgently wanted to impart.”

The best memoirs allow the reader to enter the story and find something universal in the experience portrayed. Though Linda Wolfe does an informative job of chronicling the medical details of her daughter’s stroke and recovery, and her own fear and anger, I wished for a little more breadth and artfulness in the telling, and a chance to get to know Jessica and her family before tragedy hits.

With that said, the purpose of any work, especially memoir, is to connect a community of readers, and those who have experienced the devastation of watching a loved one suffer and ultimately recover will find comfort and solace in this moving account.

Jill Bialosky is a poet, novelist, and editor at W.W. Norton and Company. Her most recent book is “History of a Suicide: My Sister’s Unfinished Life.” She lives in Manhattan and Bridgehampton.

Linda Wolfe’s books include “Wasted: The Preppie Murder” and “The Literary Gourmet.” She is a summertime resident of Sag Harbor.