Where the Dead Hide

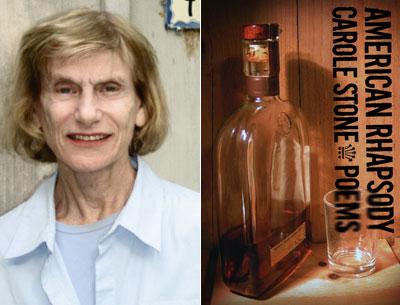

“American Rhapsody”

Carole Stone

CavanKerry Press, $16

Carole Stone’s third full-length poetry collection, “American Rhapsody,” published this year by CavanKerry Press, eulogizes a bygone era in American history, Prohibition. More, however, than a re-creation of that time, “American Rhapsody” is also an attempt to recover and understand Ms. Stone’s personal history, the loss of her mother and father when a child and being subsequently raised by aunts and uncles. This collection, therefore, seems an attempt to expiate traumatic childhood memories — both societal and personal — and, paradoxically, keep those memories alive.

Two poems illustrate this dichotomy well. In “The Past,” the poet hopes to strip history away “until nothing is left / but yourself.” We’re told that “the past swings / a noose from a tree,” a disturbing lynching image symbolizing our nation’s shameful exploits, but the poet will not “let its rope / tighten.” This revisionist wish is a rejection of our history, preparing Ms. Stone “for a new fiction / possible at a certain age.” History is not viewed here as a set of immutable facts but as a narrative for which the poet may reshape a more pleasant ending.

With “Inky Heart,” however, we learn it’s never possible to live as stated in “The Past,” with nothing but yourself outside the context of one’s personal and cultural history. Rather, the poet in “Inky Heart” is haunted by her parents, “they who turn up / everywhere.” Long after the era of Prohibition, Ms. Stone’s parents remain real presences. Because Ms. Stone cannot expurgate the memory of her parents, inextricably entwined with the often brutal excesses of Prohibition, she conjures them up, “as an invocation.” I can imagine many readers finding themselves in identical emotional straits — at once both wanting to forget and wanting never to forget.

Foremost among those alive in her “inky heart” is the poet’s father. He seems the impetus behind many poems in this book, including “Father’s Voice,” “Bundled Hundreds,” and “Homecoming.” Ms. Stone characterizes her father as not only glamorous but indifferent, as not only a financial provider but a philanderer, as both uncouth and suave. These poems reveal the ambivalent emotional connection — an ambivalence that permeates the entire collection — between poet and the memory of her father.

A bootlegger during Prohibition, the poet’s father is compared to Odysseus, the classic absentee dad. At the end of “Homecoming,” Ms. Stone offers this bitingly cynical appraisal of her father: “Only his dog / knew who he was.” Yet, in the very next poem, “On This Date,” taking a cue from Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Art of Losing,” the poet confesses that in a newspaper photograph of men breaking up a Bund rally, “my father uses his fists against evil, / making this (Write it!) / racketeer’s daughter proud.”

Some of the best poems here distill tension from the juxtaposition of the poet’s childhood idealism and the realities it confronts within the social milieu. Some of these poems are set in a time after Prohibition. In “FDR,” for example, the president’s death inaugurates a loss of innocence and childhood; in “History,” the poet watches contemporary business news, claiming, “My dream of America, / where no one would be poor, / slipping away into history,” and in “Newark” the poet balances a litany of gang activity and murdered innocents against her own discovery of lifesaving poetry in the library.

In its entirety, “American Rhapsody” is neither bombastic nor ecstatic. But most of Ms. Stone’s lyrics are deftly controlled. She fixes readers in time, never allowing us to forget the history serving as setting for most of these poems. This ambiance is created through the use of literary allusions as epigraphs. These snippets of song lyrics or quotation tap the zeitgeist, grounding readers in the tumultuous days of Prohibition.

And what a time: graft, booze, jazz, floozies, Jim Crow, murder, the Great Depression. Ms. Stone’s poems don’t stare these subjects in the eye; rather, they form the backdrop against which the poet carries out her search for “where the dead hide / in their secret clubhouse.”

Carole Stone is professor emerita of English at Montclair State University in New Jersey. She has a house in Springs.

Dan Giancola is a professor of English at Suffolk Community College. He lives in Mastic.