Winging It

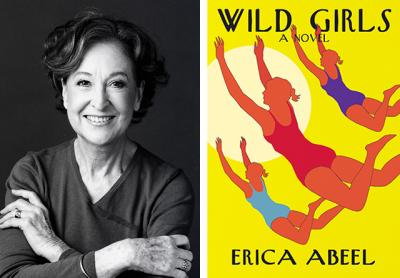

“Wild Girls”

Erica Abeel

Texas Review Press, $24.95

Erica Abeel’s “Wild Girls” follows Brett, Audrey, and Julia, friends who meet at Foxleigh — an amalgam of Barnard and Smith — as they negotiate the changing landscape of a woman’s place in America from the 1950s through the early 2000s.

Ms. Abeel, a master of the sardonic voice, sets a scene in which coeds are clustered in a “dorm’s common room for a bull session on the meaning of life. . . . Someone produced, to a chorus of groans, a box of Sara Lee brownies, and discussion shifted to the nature of despair in Kierkegaard’s ‘The Sickness Unto Death.’ ”

Brett, Audrey, and Julia are disparaging of girls “with careful hair and careful bodies,” girls like Lyndy Darling, who viewed marriage as the ultimate goal:

“Brett sometimes thought of Lyndy’s crowd and her own trio as two distinct species peaceably co-habiting the same savannah. She and the friends were warriors pitted against everything the [Lyndys] wanted; everything the world insisted you want: marriage, three weeks after graduation to a fellow who worked at General Motors, end of story. [Brett’s] little band would not fall into line so fast, oh no; they’d flex their talent in some gleaming, if amorphous future almost certainly involving the arts.”

Of course, in the world of fiction, anyone who sets out with such good intentions is bound to veer off course.

Ms. Abeel’s prose is snappy, full of wit. The sentences, even when the characters aren’t speaking, read like the quick back-and-forth dialogue of movies such as “The Apartment” and “How to Marry a Millionaire.” The book is peppered with wry observations about the hypocrisies of men, of women, and of the consequences of attempting to carve out a career as a woman in a man’s world. Audrey, an aspiring author who’s just sold her first book, comes to the conclusion that “Men . . . used language as a kind of test drive to see how things might play out, but with no commitment to making them actually happen. That’s why there were no female Einsteins, Audrey thought irritably; women wasted their best years trying to decode male language. She knocked off an article for Mademoiselle called ‘Manspeak.’ ”

After the three graduate, Brett goes to Paris to ingratiate herself with the Beats. The intimate way Ms. Abeel writes about this time period speaks to the author’s personal experience: She was there. At first, Brett worships Allen Ginsberg — whose sexual fluidity gives Brett hope that he might, one day, worship her back — but gradually her reverence is tempered by reality. “Actually, Brett had more than once wondered how, exactly, a few writer friends — Allen, Gregory, Burroughs, Kerouac — comprised a ‘generation.’ They seemed more a group of loyal buddies than a literary movement. In fact, they seemed like each other’s wives. Allen came on like a den mother, hawking their manuscripts, tending to meals.”

In Ms. Abeel’s telling, the Beats are mortal: men who bungle their way through life like the rest of the population; men who, in Brett’s interpretation, treat women as nothing more than “footnotes . . . Gregory and Cassady screwed them, Burroughs shot them in the head. And Allen? In his roll call of all that was holy women hadn’t made the cut. Only by an act of concentration worthy of Rodin’s Thinker could Allen remember women existed at all.” Brett leaves Paris, loses touch with Allen, and moves on, as one does when one has tried something and found it not to her liking.

The women enter their late 20s with a sense that they haven’t fulfilled the promise of their younger, idealistic selves. Brett says to her performance artist roommate, “Listen, I know you think I’ve, well, sold out — but not everyone has the guts to be an artist. I don’t have your vision, your drive, your . . . tenacity. Maybe I did once, but then it dissipates, like with most people. I no longer have dreams — I have a game plan. Get my Ph.D. and pay my way by living in books.” While not the most stirring proclamation, it’s a raw and true admission. People don’t want to give up on their dreams, but sometimes it’s necessary in order to survive.

Over the years there are jealousies and disagreements among the three friends, but through it all they stick together. “Wild Girls” is a realistic portrayal of the lives of women who don’t become trailblazers, who instead persevere, adapt, and remain whole.

Late in life — following deaths, divorces, misguided affairs — they find themselves hard at work on their individual creative pursuits. They have the flat in Paris, the apartment in Manhattan, the summer house in the Hamptons complete with lunches at Bobby Van’s. Their rewards. In the 1990s, the trio find themselves living in a world that Allen Ginsberg “would scarcely have recognized when he set out, hungry-eyed and geeky and desperate to be loved. A world [Brett] and her friends now inhabit like immigrants lacking language skills, but gamely winging it.”

The novel is written in the close third person, but shifts perspectives among all the women. The book begins and ends with Brett’s point of view, but nearly equal time is given to Audrey and Julia. Ms. Abeel plays with the chronology when, in the later third of the novel, she skips ahead 18 years to find the women middle-aged. A smart choice — the technique livens the narrative as we meet the characters older, wiser, with more disappointments in their rearviews.

Another jump comes at the very end. The women, now in their 70s, are gathered at Audrey’s cottage in the Hamptons. Summing up the moral, Brett says, “I’ll take humdrum happiness. . . . And the compromises, and petty self-seeking, and all that life that must go on. Audrey, what a luxury, d’you realize? To have to worry about fixing the roof. Isn’t it marvelous?”

Emily Smith Gilbert teaches creative writing at Stony Brook University. She lives in East Hampton.

Erica Abeel lives part time in East Hampton, where at BookHampton on Main Street she will read from “Wild Girls” on Nov. 5 at 5 p.m.