Of Wizards, Warriors, and What’s Next

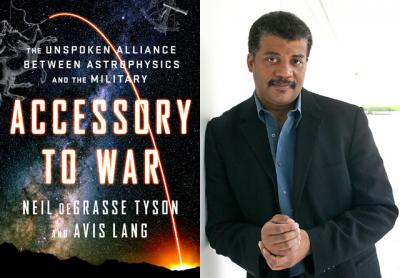

“Accessory to War”

Neil deGrasse Tyson

and Avis Lang

W.W. Norton, $30

Not since “Watch Mr. Wizard” — created by a college science and English major turned radio announcer named Don Herbert in the golden days of black-and-white TV — has there been a more genial, positive, accessible media explainer of matters scientific than the bona fide astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Off screen, Mr. Tyson is the director of the American Museum of Natural History’s Hayden Planetarium, also a veteran of various science-oriented commissions and boards, and an award-winning author on matters astrophysical, from the Big Bang’s foundational fury to voracious black holes to the rise and fall of poor ex-planet Pluto (though new research suggests it may soon regain its former celestial status).

Mr. Tyson’s latest book, written with his longtime researcher and editor, Avis Lang, has a darker and more political tone.

As both the Trump administration and its critics would do well to study, “Accessory to War” lays out in often overwhelming detail the way scientific progress has from time immemorial been prompted, funded, often commandeered or co-opted by mankind’s warriors, their political leaders, and policymakers — for better and (too often) for worse.

But Mr. Tyson also reveals the personal journey that led him to write the book, in part perhaps as expiation for his complicity in, in the words of the subtitle, “The Unspoken Alliance Between Astrophysics and the Military.”

Growing up in anti-Vietnam War America, he says, images of the suffering on all sides “embedded themselves in my mind.”

They returned when his then-9-year-old daughter scampered by naked in a way eerily reminiscent of that 1972 Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of a little Vietnamese girl fleeing U.S. napalm. “In that fleeting moment they were one and the same,” he writes.

The real epiphany came at an April 2003 Space Foundation symposium in Colorado Springs — jammed with military men, aerospace industry leaders, and fellow scientists — when attention suddenly shifted to CNN coverage of the U.S. “shock and awe” assault on Baghdad. And Mr. Tyson was shocked at the audience reaction.

“Every time a corporation was identified as the producer of a particular instrument of destruction, its employees . . . broke into applause,” he recalls. “I was anguished. . . . In video games you’re expected to cheer when you destroy your virtual targets and proceed to the next level. But it’s hard to accept that kind of behavior when your targets are real. People die. . . .”

“Then and there,” he continues, “I grasped the unattractive, undeniable fact that without the Space Symposium, without the many symposia like it . . . without the power sought by its participants — both for themselves and for the nations they represent — and without the tandem investments in technology fostered by that quest for power, there would be no astronomy, no astrophysics, no astronauts, no exploration of the solar system, and barely any comprehension of the cosmos.”

And Mr. Tyson scrolls through history to find an amazing antecedent to this view.

Back in 1696, he notes, the Dutch astronomer and mathematician Christiaan Huygens saw military conflict as one of several necessary prods to progress and creativity — that “such a mixture as Misfortunes, Wars, Afflictions, Poverty and the like were given us for this very good end, viz. the exercising our Wits and Sharpening our Inventions; by forcing us to provide for our own necessary defence against our Enemies. . . .”

“And if Men were to lead their whole Lives in an undisturb’d continual Peace, in no fear of Poverty, no danger of War, I don’t doubt they would live little better than the Brutes, without all knowledge or enjoyment of those Advantages that make our lives pass on with pleasure and profit. . . .”

Indeed, Mr. Tyson concedes that star charts, calendars, chronometers, telescopes, maps, compasses, rockets, satellites, drones, much of modern electronics and communications began not as purely “inspirational civilian endeavors. Dominance was their goal; increase of knowledge was incidental.”

He finds fascinating tidbits in sorting through the procession of this not really so covert connection.

Astronomers developed useful knowledge for determining one’s position on earth and knowing when night would fall and daybreak — or eclipses — occur, critical stuff for commanders of armies and navies.

The Greek military inventor and mathematician Archimedes reportedly conceived a “burning mirror” to redirect and focus sunlight to enflame a fleet of Roman ships, circa 213.

The first real telescope was created by a spectacle maker for the military commander in chief of the Netherlands in 1608 during the Catholic-Protestant Eighty Years’ War.

Galileo reportedly learned of it and made better ones — first achieving three times magnification, eventually 60 times “to discover [the enemy] at a much greater distance,” as he explained, “so that for 2 hours and more we can detect him before he detects us. . . .”

Early photography and spectroscopy became the midwives of astrophysics, providing visible images of heavenly objects and — by analysis of the wavelengths of light they emitted — an idea of their physical composition.

In more recent times, World War II and the Cold War accelerated military and scientific progress, the space race, U.S. men on the moon. And the Cold War’s end produced a devastating, corresponding de-escalation. The number of aerospace companies fell from 75 to 62 by the fall of the Berlin Wall and to just five by 2001, Mr. Tyson notes — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, and General Dynamics — despite a resurgence in defense spending prompted by the Vietnam War and, with only a slight pause, continuing thereafter.

That outlay was kicked into even higher gear by the 9/11 attacks and U.S. responses.

In fact, the Iraq war was a bloody showcase for new space-based technology, with satellites both military and civilian enlisted to provide vastly improved communications, observation of the enemy, guidance for friendly forces and their weapons — tanks, jets, missiles, and more. Returns on one global aerospace index rose nearly 90 percent, compared with a 60-percent rise in global equities, Mr. Tyson reports.

Along with the rise in defense or dual-use space spending came an escalation in aggressive Washington rhetoric and rationale for U.S. supremacy in space.

Even months before 9/11, a commission headed by soon-to-be-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld invoked the threat of a “Space Pearl Harbor” and called for “power projection in, from, and through space” so that America would “remain the world’s leading space-faring nation, [able] to defend its space assets against hostile acts and to negate the hostile use of space against U.S. interests.”

An “altogether a grandiose and open-ended agenda,” Mr. Tyson calls it.

And while some subsequent administrations dialed back to simply maintaining a “competitive advantage” in space, we now see re-escalation. “It is not enough to merely have an American presence in space; we must have American dominance in space,” Vice President Mike Pence recently declared.

But the author explains how the proliferation of other nations in space, Russia and China foremost among them — with all their satellites, missile stockpiles, progress on killer energy beams, and already demonstrated long-range internet hacking — make dominance for any one of them increasingly unlikely.

Although not altogether opposed to President Trump’s proposed Space Force in recent interviews, Mr. Tyson here warns that preparation can lead to extermination. “Each further step on the continuum escalates the danger, from simply operating in space, to operating militarily, to operating aggressively, to operating lethally.”

The fallout, figurative and literal, from war in space — destruction or disruption of satellites critical to communications, global positioning, and national defense, not to mention actual space-based chemical, biological, or nuclear missile attacks on terrestrial targets, and counterattacks in kind — would be too dangerous and costly for any rational consideration, Mr. Tyson believes.

“An optimist might contend that nobody but a rational actor would ever be permitted to make such decisions,” he writes, “but anybody who has watched the 1964 movie masterpiece ‘Dr. Strangelove’ or witnessed the rampant irrationality of the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign is unlikely to agree.”

Like many others before and since, he calls for more international coordination and cooperation in space, despite the apparent hollowness of many such pacts, plans, and promises.

The International Space Station, after all, seems likely to continue operations at least through 2024, he suggests, with mixed crews and heavy lifting by Russian rockets despite enflamed Moscow-Washington relations.

Taking pie in the sky to new heights, non-scientists might say, Mr. Tyson also suggests astrophysical solutions to some potential causes of war. Noting the critical importance to all high tech of “rare earth elements” now largely controlled by China, for example, he pictures widespread mining of asteroids found to contain them.

And to ensure sufficient water for our planet, there could even be capturing of comets, some of which “contain as much water as the entire Indian Ocean,” he writes. “The way to snare a comet is to match orbits with it and break off a piece, which should be very easy.”

Of course some sources of war have little to do with natural resources: ideology, religion, national pride, a leader’s lust for power, as we have been reminded by 9/11, subsequent terrorism, the violence attending fear and hatred of “the other” worldwide.

Mr. Tyson knows this. Early on in this book he recalls that a down-to-earth demonstration of bellicose human nature after a banquet of the American Astrophysical Society in January 1991 was cut short by America’s launching Operation Desert Storm in the Persian Gulf.

Walking off “some confused energy” in the streets of Philadelphia, he shouted to a 20-something mechanic working late: “Did you hear we went in?”

The answer — “Fuckin’ A! We’re at war!” — came back with a giddy fist pump.

“Probably I should have seen that coming,” Mr. Tyson concedes. “He was plugged into a primal passion that has energized so many wars across the millennia.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson is a part-time resident of East Hampton.

David M. Alpern ran the “Newsweek On Air” and “For Your Ears Only” network radio shows for more than 30 years, hosted weekly podcasts for World Policy Journal, and now voices news stories for the visually impaired at gatewave.org from his home in Sag Harbor.