A Woman in Full

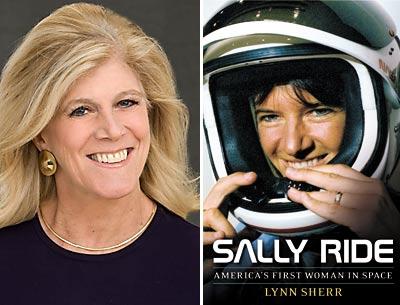

“Sally Ride”

Lynn Sherr

Simon & Schuster, $28

I’m going to come clean. The last time space flight held my attention was on July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 touched down on the moon. In the decades since, I have been more aware of NASA’s failings: the aborted Challenger launch in 1986 that killed, among others, a social studies teacher. Or the terrible re-entry of the Columbia in 2003 that took the lives of seven astronauts. If we’re not finding intelligent life on Mars, I thought, who cares?

Yet, I couldn’t put down “Sally Ride: America’s First Woman in Space.” In her new biography, Lynn Sherr had me gripped and, I’ll confess, feeling like I’d lost an old friend by the final chapters.

“Who was Sally Ride?” Ms. Sherr, a former ABC journalist, reports asking a classroom of kids in the book’s introduction. That she was the first American woman in space — third in the world, if anyone’s counting — is just part of the story. Ms. Ride was a scholar, an educator, physicist, championship tennis player, and a feminist first. Nonetheless, if Ms. Ride were to have left her own autobiography behind, it would have been whippet thin, claims Ms. Sherr. Words were always Sally’s last resort. Seizing the day was all that mattered; explaining how she felt about it only ruined the fun.

Ms. Sherr struck up an instant friendship with Ms. Ride on being sent by ABC News to cover NASA in 1981. Their association ebbed and flowed until Ms. Ride’s early death from cancer in 2012 at 61 years old. It was Ms. Ride’s long-kept secret that in large part drove Ms. Sherr’s narrative quest — that was her 27-year love relationship with Tam O’Shaughnessy, her business partner. Only in her obituary did Ms. Ride “come out” to the world at large. If she couldn’t tell me she was gay, Ms. Sherr asks herself, what kind of friend was I? Yet, no biographer is more equal to the task of cracking the code of Sally Ride than Ms. Sherr, who wonders, somewhat painfully, if she knew her friend at all.

Ms. Sherr had unfettered access to myriad sources — Ms. Ride’s mother, sister, childhood friends, ex-husband, former lovers, teachers, and many of the surviving astronauts of her NASA class, who dubbed themselves the Thirty-Five New Guys (TFNG). The absence of Ms. Ride’s input — she left little trace of her take on much of anything beyond interview quotes — doesn’t mar its perspective. The book succeeds in showing Ms. Ride, to borrow from Tom Wolfe, as a woman in full, in addition to being an astronaut with “the right stuff.”

The author puts to rest the myth that Ms. Ride had “rocket dreams” since childhood. She traces Ms. Ride’s early trajectory as a California girl who won scholarships to the prestigious Westlake School for Girls and later Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania as a ranked tennis player. “Tennis balls don’t bounce in the snow,” said her mother, Joyce. Ms. Ride ended up back under the California sun at Stanford University as a junior transfer student, and she ultimately pursued a Ph.D. there in astrophysics. Her body, she felt, wasn’t up to the physical punishment of a tennis career, even as she was Stanford’s number-one player.

Ms. Sherr sets the story in the context of the women’s movement, repeatedly touching down on milestones that made up the groundswell for equality of which Ms. Ride was a part — among them, Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique,” the passage of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, Title IX, and Sandra Day O’Connor’s appointment to the Supreme Court. Growing up, Sally and her sister, Bear, were singularly unaware of a glass ceiling.

“The Rides raised their daughters without preconceptions or gender constraints,” reports Ms. Sherr, with a characteristically wry quote from Ms. Ride’s mother: “I guess I was oblivious to the fact that men were in any way superior.” At NASA, which was slow to change, Ms. Ride ultimately benefited from a growing unease at the exclusion of minorities and women.

“Sally wanted to be famous,” recalled a friend. “But she wanted to win the Nobel Prize.” Ms. Ride never had any doubt that she would achieve her goals, recasting any derailment ultimately as her own decision. But space travel didn’t occur to her until at age 26 she read an article on the front page of The Stanford Daily with the headline: “NASA to Recruit Women.” Ms. Sherr included a reproduction of that article, as well as Ms. Ride’s quaint handwritten note requesting application materials.

Out of 25,000 requests, 8,079 would-be astronauts applied. A field of 5,680 was narrowed to 1,251 women, of which 659 qualified. Six women were chosen as members of the TFNG’s team. Ms. Ride’s brilliance, calm, and ability to work effectively in a team would put her first to go up in the Challenger in 1983.

What emerges out of Ms. Sherr’s reporting is a woman of contradictions — “an introvert who spent much of her life on the public stage . . . a physicist who loved Shakespeare, a world-renounced space traveler who saw herself as an educator.”

What seems to plague Ms. Sherr unnecessarily is Ms. Ride’s reluctance to come out, even as friends like Billy Jean King were taking the risk. There is even the suggestion, though Ms. Sherr never says so directly, that Ms. Ride married her teammate Steve Hawley to blend more seamlessly into NASA’s culture. They divorced after Ms. Ride left NASA, though her presence on subsequent investigative and strategic planning panels would lend the agency credibility in difficult times.

Ms. Ride was someone who didn’t give a damn what anybody thought. But she was savvy enough to know that what people think makes a difference to the opportunities that come your way. “She knew what she wanted,” said Mr. Hawley. She was going fly with NASA. Later, as C.E.O. of Sally Ride Science — an enterprise that encourages girls to pursue math and science careers — she wasn’t going to let a parent’s regressive views of her sexuality spoil a child’s chance at pursuing her bliss. “I think the gay thing is very secondary to who Sally was,” said her mother, closing the discussion.

No doubt Ms. Ride would have cringed at Ms. O’Shaughnessy’s characterization of her as “just a loving little puppy dog” behind closed doors. Nonetheless, it’s important to know that Ms. Ride, so careful in public, had her softer side, along with a wicked sense of humor. Still, for all the personal revelations, I think she would have been glad for a biography that makes her journey so accessible.

Readers will come away knowing what a O-ring is without getting mired in tech speak and will understand exactly what’s so cool about weightlessness. They’ll also recognize that Ms. Ride was decades ahead of her time. “It’s remarkable how beautiful our planet is, and how fragile it looks,” she told a reporter who wanted to cast her flight in “sexy” spiritual terms. Ms. Ride saw space flight as a way of looking back on ourselves from a broader perspective.

Like her subject, a born educator, Ms. Sherr strives above all to be understood. She’s not going for pyrotechnics in her prose or, for that matter, hagiography. Plain and simple, she aimed to do justice to the legacy of her friend, a true American heroine. She has achieved her goal in this tribute, a thoroughly readable biography.

Ellen T. White, former managing editor of the New York Public Library, is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” an anthology of romantic women of power. She lives in Springs.

Lynn Sherr lives in New York and East Hampton.