Wrestling the Sprawling Beast of Rock ’n’ Roll

“50 Years

of Rolling Stone”

Jann Wenner

Abrams, $65

The last 18 months have seen the death of an inordinate number of rock ’n’ roll musicians.

It is a matter of course, of course, that 60-odd years after alchemists like Chuck Berry brought a new musical form into being, heroes of the genre’s first decades are passing from the stage. At the same time, the form’s high mortality rate has remained sadly consistent; while Berry, rock ’n’ roll’s duck-walking prototype, was 90 when he died in March, the singer Chris Cornell was just 52 when, two weeks ago, he took his own life hours after performing with his band, Soundgarden.

Berry, a brash, ornery guitarist and rock ’n’ roll’s first poet. Cornell, a longhaired, imposing, somewhat sinister and oft-addicted vocalist at the forefront of a once-immensely popular subgenre dubbed grunge. Recently preceding these men in death were the likes of David Bowie, Prince, Glenn Frey, Gregg Allman, and Leon Russell. Each quite different from the others, each added a unique contribution to the sprawling beast known as rock ’n’ roll.

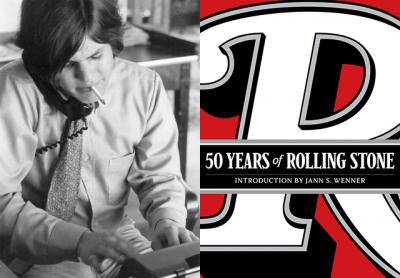

In 1967, a 21-year-old San Franciscan, having lost his short-lived gig as entertainment editor for an alternative weekly, sought the counsel of Ralph Gleason, The San Francisco Chronicle’s jazz and pop critic and a mentor to the young scribe. “The idea that clicked was a ‘rock & roll newspaper,’ ” Jann Wenner writes in the introduction to “50 Years of Rolling Stone,” a 288-page tome of a size and weight befitting its storied subject.

Mr. Wenner, who bought a house in Montauk in 2009 and was an East Hampton resident before that, writes of his magazine that “rock & roll needed a voice — a journalistic voice, a critical voice, an insider’s voice, an evangelical voice — to represent how serious and important the music and musical culture had become, in addition to all its manifest entertainment value; a place where fans and musicians could talk to one another, get praise, advice, feedback; someplace we could shout, ‘Hail hail rock & roll, deliver us from the days of old.’ ”

By then, the “devil’s music,” spawned deep in the American South by Berry, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Carl Perkins, and so many others, had grown up. It was now the sound of “cultural and political upheaval, freedom from drug and sexual and social repression,” Mr. Wenner writes. “It was the post-World War II baby boom coming of age — and determined to have its way.”

“Like a Rolling Stone,” an angry, six-minute-plus song by Bob Dylan released in 1965, was also the title of an essay Gleason wrote for The American Scholar, one Mr. Wenner describes as “a personal manifesto and philosophical survey of the cultural and popular music landscape.” Naming his “rock & roll newspaper” after that title was also, he writes, a nod to one of his favorite artists, the Rolling Stones, who in turn had named themselves for “Rollin’ Stone,” a song by McKinley Morganfield, a.k.a. Muddy Waters, the Mississippi-born musician who had migrated to Chicago and electrified his country blues, thereby charting an inevitable course for the sounds that would follow.

From the start, Mr. Wenner was daring, lucky, and good. Tom Wolfe, Annie Leibovitz, and Hunter S. Thompson were among the first to document, in words and images, the music, politics, and culture that Rolling Stone fearlessly chronicled. With a surfeit of rock ’n’ roll artists producing now-classic music at a prodigious clip, Richard Nixon, the Vietnam War, and the sexual revolution, all experienced through a kaleidoscope of psychedelic drugs, Rolling Stone had plenty to document, and Mr. Wenner, his staff, and their subjects had plenty to say.

Thompson’s “Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas,” Mr. Wenner writes, “became the ‘Catcher in the Rye’ of our times — and then his coverage of the 1972 elections was so brilliant, funny, and original that both he and Rolling Stone became legend.”

Later, Mr. Wolfe would serialize “The Bonfire of the Vanities,” which Mr. Wenner calls “our triumph.” “Tom wanted to write a new chapter on deadline for every issue for a year, and we would work in this rhythm, right on the very edge of possible disaster, just as Charles Dickens had published a century earlier. Tom told me it was not for the faint of heart, but where else could you have so much fun?”

“50 Years of Rolling Stone” is abundant with photography, iconic moments captured by Ms. Leibovitz, Ethan Russell, Baron Wolman, Richard Avedon, Herb Ritts, and Mark Seliger, among others. Standouts include Mr. Russell’s shot of Mick Jagger, an androgynous prince of darkness sashaying before thousands of spellbound subjects in 1969; Jimi Hendrix kneeling before the guitar he had just set afire at the Monterey Pop festival in ’67; a spread depicting a naked Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, each gazing at the camera with the intensity of a turbulent, doomed soul; a pensive Michael Jackson on the cusp of adolescence, and a seated Jimmy Page, head thrown back to drain a bottle of Tennessee whiskey, he and his cohorts in Led Zeppelin soon to enthrall another audience, somewhere in America in 1975.

For better or worse, Rolling Stone has tracked Western popular culture. As television consumed more time and attention, the magazine devoted more coverage to the medium and its own stars. As rock ’n’ roll aged and splintered ever further, hip-hop artists stepped in and assumed prominence in its pages.

In the 1990s, the baby boom generation elected one of its own to the White House, and Rolling Stone embraced Bill Clinton’s candidacy and railed at his tormentors on the right. Meanwhile, rock ’n’ roll’s penchant for reinvention manifested again with the sound emerging from Seattle and embodied by vocalists like Mr. Cornell, Kurt Cobain, Layne Staley, and Eddie Vedder. (All but Mr. Vedder are now deceased; drugs are clearly a constant in the fast-paced world of rock ’n’ roll.)

With the 1960s a distant memory, Rolling Stone soldiered on in the new millennium, but George W. Bush (“adjudged by Princeton historian Sean Wilentz in a Rolling Stone cover story to be perhaps the worst president of all time,” Mr. Wenner writes) and his post-9/11 misadventure in Iraq gave the magazine new lifeblood. Rock ’n’ roll took note, too: The invasion of Iraq “was behind Green Day’s 2004 album, ‘American Idiot,’ which helped turn the band into one of rock’s biggest, connecting a younger generation with the sound of punk guitars,” Mr. Wenner writes. At the same time, the new century’s sonic signature “included the pop of Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake, who ushered in a new kind of celebrity that would go on to be shaped by the age of social media.”

“50 Years of Rolling Stone” would be well worth its sticker price with the photos and Mr. Wenner’s reminiscences alone. It would be incomplete, however, without a sample of the magazine’s interviews, and artists like John Lennon, Mr. Jagger, Bono, and Mr. Dylan hold forth in extended excerpts. Mr. Dylan, who turned 76 last week, told the magazine in 2001 that “Every one of the records I’ve made has emanated from the entire panorama of what America is to me. America, to me, is a rising tide that lifts all ships, and I’ve never really sought inspiration from other types of music.”

Hail hail rock ’n’ roll, deliver us from the days of old.