The Year's 10 Best Books

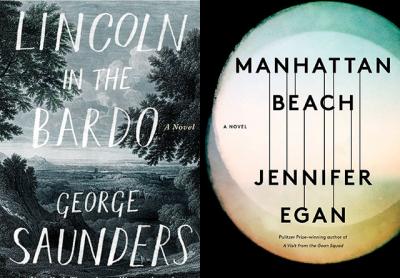

“Manhattan Beach” and

“Lincoln in the Bardo”

Interesting that two of America’s keenest observers of contemporary life turned to the past for their latest work. Coincidence, or have current events overshadowed the possibilities of fiction? Jennifer Egan’s book follows a female diver at the Brooklyn docks during World War II, while George Saunders’s inhabits a number of voices surrounding the death of Abraham Lincoln’s son Willie in 1862. Neither is as good as these authors’ best works, but in an off year for American fiction, both were still among 2017’s most satisfying.

“Killers of the Flower Moon”

by David Grann

A work of nonfiction comparable to “In Cold Blood” and “The Executioner’s Song,” and the year’s best book. It tells the story of the Osage Indian tribe, who negotiate the rights to their mineral-rich land in 1920s Oklahoma — only to come under siege from murdering land barons. As the deaths pile up, J. Edgar Hoover comes to investigate, a case he will later use to increase the profile and power of the F.B.I. A story so rich and unique it seems impossible it is only being told now.

“Leonardo da Vinci”

by Walter Isaacson

When it comes to biographical subjects, Mr. Isaacson doesn’t mess around. He has tackled Steve Jobs, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, and now da Vinci, his most mercurial subject yet, “illegitimate, gay, vegetarian, left-handed, easily distracted, and at times heretical,” as Mr. Isaacson writes. There are two arrests for homosexual acts, a blood feud with Michelangelo, and a stint as a spy for the Borgias. In his free time Leonardo managed a little work, too, including art, engineering, geometry, botany, physics, and much else. Nothing, it seems, escaped this genius’s mind, for which the very term “Renaissance man” appears to have been invented.

“Lost City of the Monkey God”

by Douglas Preston

Yet another nonfiction title that surpassed most of this year’s novels. In 1940, Theodore Morde, a journalist, journeyed to the Honduran jungle to investigate the myth of a lost city. He returned with the news that he had discovered it, with artifacts in hand, only to mysteriously commit suicide before revealing where it was located. Seventy-five years later, Douglas Preston and a team of scientists go in search of Morde’s trail, encountering along the way a “Raiders of the Lost Ark” bevy of dangers, everything from quicksand to jaguars. A great adventure and gripping read.

“Meet Me in the Bathroom”

by Lizzy Goodman

An oral biography of the second great era of rock in New York City, the decade starting in 2001. Ms. Goodman pastes together hundreds of interviews from the period’s most seminal bands: the Strokes, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Vampire Weekend, etc. There is plenty of decadence, of course, and a mother lode of gossip — the Strokes and Ryan Adams have a go at each other, for example. But the book also explains how these bands met the challenge of new technology, managing to survive and even thrive during the digital revolution. Though it ends in 2011, it already feels nostalgic. Can you imagine these bands emerging in today’s Manhattan?

“The Force”

by Don Winslow

The fallen hero of Don Winslow’s ambitious police novel, Denny Malone, is the kind of character who would have been played by Al Pacino in his prime, as directed by Sidney Lumet. Denny is tough, smart, foulmouthed, and the best cop in Manhattan North — and, oh yes, he and his fellow officers have stolen millions in drug money. Stephen King said “The Force” was “like ‘The Godfather,’ only with cops.” But it is also a sprawling overview of New York City, depicting a gritty Manhattan awash in hypocrisy and greed, both high and low. And all of it written in Mr. Winslow’s spare, machine-gun-fire prose.

“Sticky Fingers”

by Joe Hagan

A biography that the subject himself, Jann Wenner, called “deeply flawed and tawdry,” so you know it’s good. It follows the inception of Rolling Stone in 1967 to the near present — though it’s in the era of the early 1970s that the book really sings. Drugs are everywhere, including with the journalists themselves, who were occasionally paid in cocaine. Mr. Wenner is depicted as a mass of dichotomies: fearless and insecure, generous and manipulative, straight and gay. The story ends with the erroneous campus rape story, which cost the magazine millions of dollars and at least some of its reputation. But who could dispute Rolling Stone’s vast influence, or that its story needs to be told?

“Pachinko”

by Min Jin Lee

“History has failed us, but no matter,” reads the first line of Ms. Lee’s new novel, her second after “Free Food for Millionaires.” “Pachinko” is a more ambitious affair, spanning four generations of a Korean family trying to survive under Japanese rule. The metaphor is the Japanese pachinko game itself, something of a hybrid of pinball and slot machine. Fortunes rise and fall in this epic tale, and the mercurial nature of destiny is explored through dozens of characters. But what seems both lasting and timely about “Pachinko” is the struggle and triumph of the immigrant experience, Ms. Lee giving dignity to what seems like an endlessly besieged group.

“Red Famine”

by Anne Applebaum

It is nearly impossible to imagine a leader purposely starving to death three million of his own people — unless, of course, that leader’s name is Joseph Stalin, of whom we have come to expect such things. Stalin apologists have always contended that the suffering in Ukraine (primarily between 1931 and 1933) was simply a matter of bad economic policy. But Ms. Applebaum’s research confirms what others had long theorized: In order to quell various rebellions in Ukraine, Stalin’s regime systematically cut off all access to the region’s food. The results were gruesome, as the population was reduced to eating dogs, garbage, and eventually each other. A grim but necessary lesson in bureaucratic barbarity.

Kurt Wenzel is a novelist and regular book reviewer for The Star. He lives in Springs.