Year’s 10 Best: Our Man in Letters Picks ’Em

“Chance” by Kem Nunn

A strange and unique San Francisco noir that is by turns dark, thoughtful, and oddly funny. Kem Nunn, who is best known for his “surfer noir” trilogy, has broadened his palette here to include subtle satire. His hero, Eldon Chance, is a self-absorbed neuropsychiatrist, and the author puts him through the ringer. When a divorce forces the doctor to sell off a precious antique desk, he finds himself in the midst of a series of unhinged and violent characters.

It is a mystery with touches of “Vertigo,” though the real puzzle is how Mr. Nunn keeps you asking, “Should I be laughing at this?” even as he submits Chance to greater and greater humiliations. (Scribner, $26)

“The Bone Clocks” by David Mitchell

Apparently David Mitchell can do anything. In novels like “Cloud Atlas” and “Ghostwritten,” he wrote with equal skill about the past, the present, and the future, in the male or female voice, from anywhere on the globe and at any epoch. His stories are told simultaneously, side by side in the same novel, then usually conclude with a slam-bang ending that neatly ties all the dissonant threads together.

"The Bone Clocks" begins simply enough, with the daughter of an English pub owner, Holly Sykes, who seems to have psychic powers. Mr. Mitchell then takes us through six different places and timescapes, finally culminating in Ireland in 2043. Once again he displays his astonishing toolbox, which this time includes elements of pulp, science fiction, and classic 19th-century novels. Another startling performance that will satisfy brainiacs and pop-fiction lovers alike. (Random House, $30)

“Tennessee Williams:

Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh” by John Lahr

An exploration of one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. John Lahr, theater critic for The New Yorker, doesn’t get dragged down into the slog of standardized biographies — born here, went to school there, etc. — but concentrates on the plays themselves: their heroes and heroines and their relationship to their creator. Consequently he has produced a book that seems to get closer to the real Tennessee than any of the mountain of previous biographical works.

Yes, you’ll find the pills, the boys, Marlon Brando gossip, and the tragic creative slide in these pages, but also the genius and great humanity of the giant of the American theater. (W.W. Norton, $39.95)

“Bad Paper: Chasing Debt From Wall Street to the

Underworld” by Jake Halpern

Just when you thought there was nothing sleazier than banks that trap helpless borrowers with predatory loans, enter the people who collect on that debt. Jake Halpern’s nonfiction expose about rogue debt collectors is so riveting you’ll find yourself wondering, “Can this really be true?” But it is. The story is centered on a former banking executive, Aaron Siegel, who buys $14 million in debt accounts worth $1.5 billion.

When part of the portfolio is stolen, Mr. Siegel partners with an armed robber, Brandon Wilson. To recover some of the accounts, this charming (and oddly sympathetic) character supplements his physical threats by showing scars from his various gunshot and knife wounds. And they haven’t even started collecting yet! This will include screaming, intimidation, and the targeting of the elderly. The story is by turns infuriating, sad, and exhilarating. Kinda like, well, the free market. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $25)

“Lila” by Marilynne Robinson

Marilynne Robinson returns to the fictional town of Gilead for another moving meditation on love and religion. Lila is an orphaned girl who at age 4 turns up half-dead on a porch. She is rescued by Doll, a cagey drifter who takes Lila on a harrowing journey through Depression-era America. Years later, when Lila embarks on a romance with a local minister, she is forced to reconcile her hardscrabble youth with a new life within the folds of the church.

The miracle of the novel is watching the flawed Lila bring grace to the sheltered minister, who knows little of what he preaches. With “Lila,” Ms. Robinson secures her post as one of America’s best and most important novelists. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26)

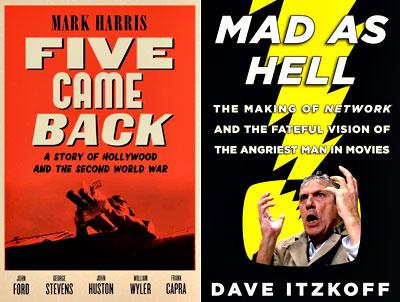

“Five Came Back”

By Mark Harris

It’s the story of five Hollywood directors who participated in World War II and how the war changed them. John Ford, William Wyler, Frank Capra, George Stevens, and John Huston all volunteered for active duty after Pearl Harbor (Ford just prior) and all shot footage for Uncle Sam. There’s some good gossip here, as when the irascible Ford chides John Wayne for playing war heroes on screen instead of volunteering, and Capra’s technical problems in capturing the wide panorama of D-Day. But there is great gravitas as well, including Stevens, who was with the first Allied unit to enter the Dachau concentration camp (it took him years to recover).

As for the films that followed the war, Mark Harris composes a fascinating juxtaposition of two — Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” and Wyler’s towering “The Best Years of Our Lives” — reminding us that Capra’s movie was a flop at the time, while Wyler’s darker film may have hinted at the director’s own difficulties in adjusting to civilian life. (Penguin, $29.95)

“Zone of Interest”

By Martin Amis

Say what you will about Martin Amis (who remains a perpetually divisive figure), but you have to admit he has guts. Ever the provocateur, the author here has concocted no less than a black comedy set in a concentration camp. The novel is told from the Germans’ point of view, where Nazi underlings find themselves in bureaucratic hell, trying to deliver on the ever-increasing “demands” of the Chancellery.

It you think Mr. Amis is disrespecting the Holocaust, forget it. The author’s virtuoso talents account for some of the most unflinching horror in modern fiction, and the “comedy,” such as it is, is really just a device to provide another entrance point toward loss. The author gives it to you straight, then makes you swallow the rest as humor. “We are the saddest men in the Lager,” comments one soldier. “We are in fact the saddest men in the history of the world.” Amen. (Knopf, $26.95)

“This Changes Everything”

By Naomi Klein

Finally, a solution to climate change: Dim the rays of the sun with sulfate-spraying helium balloons, thereby mimicking the cooling effect of volcanic eruptions — or so suggests one madcap scientist cited in Naomi Klein’s new work. The author makes a withering counterargument to climate deniers and those who think it is a problem to be solved by “the market” or scientific Hail Marys.

The only thing that will save us, she argues, is a new relationship with the planet. Stop buying things, stop making things, shrink G.D.P.s, live simpler. Her vision can at times lean heavy on the good guys versus bad guys theme, but there’s no denying this is an important work about mankind’s most urgent challenge. (Simon and Schuster, $30)

“Mad as Hell: The Making of ‘Network’ and the Fateful

Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies” by David Itzkoff

Put unhinged people on television in an attempt to drive up ratings but muzzle them if they say anything that compromises the multinational corporations that own the networks themselves. . . . Paddy Chayefsky’s landmark 1976 screenplay was deemed “paranoid” at the time, but now seems prescient (and perhaps didn’t go far enough). In a series of interviews with cast and crew of the Oscar-winning film, David Itzkoff tracks the many battles the writer fought to bring his singular vision to the screen.

“I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore.” This is the famous lament of “Network’s” manic newscaster, Howard Beale, but it just as easily could be Chayefsky’s battle cry for the Hollywood establishment who tried to tame him. (Times Books/Henry Holt, $27)

“Capital in the Twenty-First Century” by Thomas Piketty

Strange how this blockbuster number-one best seller is on so few of this year’s top-10 book lists — or is it? Thomas Piketty’s book takes a hard look at income inequality and also provides the phrase of the year with “drift toward oligarchy.” Tracking 20 countries going back to the 18th century, the author debunks spurious conservative talking points such as trickle down, austerity, and lower tax rates for the wealthy.

But wait, the rich just work harder than you and I, right? Not according to Mr. Piketty’s data, which identify capital as increasing far faster than economic growth, which means that inheritance is the most significant factor in determining personal wealth. What does all this inequality mean for the future? Increased poverty, war, and the end of democracy. Okay, not the funniest book of the year, but by far the most important. (Belknap, $39.95)

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels “Lit Life,” “Gotham Tragic,” and “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.