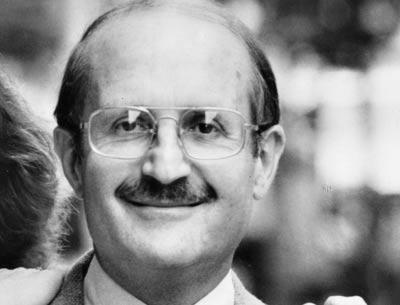

Yehuda Nir, 84

Growing up Jewish in pre-Hitler Poland with a series of nurses and nannies who sang to him in a Babel of native tongues, Yehuda Nir could read or speak seven languages by the time he was 10. The one that helped save his life, though, he did not learn until he was 11, soon after his father was murdered — Latin, which allowed the blond-haired child not only to pass as a Roman Catholic, but even to serve as an altar boy.

“Within a week, I knew the catechism inside out,” Dr. Nir wrote in a memoir, thinly disguised as fiction, that was published in these pages in 1995. “I can recite Pater Noster in Polish today, this very minute. . . . I wouldn’t be here to write this if I didn’t know it.”

Dr. Nir, a frequent traveler to Israel whose house in Springs overlooking Gardiner’s Bay was “one of his favorite places on earth,” said his daughter, Sarah Maslin Nir, died on Saturday at home in Manhattan at the age of 84. His long life was defined to an enormous extent by his struggle to survive the war; its horrors stayed with him, always ready to surface, especially if the talk turned to Germans or Germany.

“He lived on the dark side of life,” said the sculptor Audrey Flack, who often went yard-saling here with Dr. Nir and his wife, Dr. Bonnie Maslin, as they looked for kitschy porcelain figurines to add to their large collection. “The toys I never had,” he once said.

He never forgave, although in later life, at a Holocaust conference, he became friendly with Gottfried Wagner, the great-grandson of Hitler’s favorite composer, whose music is unofficially banned in Israel. Dr. Nir and Herr Wagner, an advocate of dialogue between Jews and the offspring of families that were once actively Nazi, sometimes appeared together before audiences at venues including the Jewish Center of the Hamptons in East Hampton and Temple Adas Israel in Sag Harbor, and they collaborated on an opera, “The Lost Child,” based on Dr. Nir’s 1989 book, “The Lost Childhood.” The one-act opera “doubles the value of my book,” he later wrote, “intensifying the emotion of my story, my story being not what has become of me, but the tragedy of that period.”

Reprinted by Scholastic Press in 2002, “The Lost Childhood” is now used in high school classrooms around the country.

When the war ended, Yehuda, with his mother and older sister, managed to get to Palestine on forged papers. There he abandoned “Juliusz Gruenfeld,” the name he had been born with on March 31, 1930, and chose a Hebrew surname, Nir, that means “plowed fields” in that language. He studied medicine at Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School and in Vienna, and learned English along the way by reading Shakespeare, before coming to the United States in 1959 to take up medical residencies.

As a psychologist in this country, Dr. Nir specialized in post-traumatic stress disorder and the treatment of terminally ill children; he became chief of child psychiatry at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in 1979. From that time until he fell ill about four years ago, he was also affiliated with Weill Medical College of Cornell University at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Many of the adult patients he treated in private practice were fellow Holocaust survivors.

With his wife, Dr. Maslin, also a psychiatrist, Dr. Nir wrote a number of self-help books on relationships, among them “Loving Men for All the Right Reasons” and “Not Quite Paradise: Making Marriage Work.” The couple, who were married in 1973, practiced together in Manhattan for years.

In addition to his wife and daughter, Dr. Nir leaves three sons. Daniel Nir, of Manhattan and Southampton, and Aaron Nir, of Manhattan and Bridgehampton, are the children of a first marriage. David Nir, also of Manhattan, is his son with Dr. Maslin.

Toward the end of his memoir in The Star, titled “I Was Born With an Accent,” Dr. Nir, ever the linguist, wondered “in what language will they write my epitaph,” and answered his own question: “Please, only in Hebrew.” His funeral service, attended by some 400 people, was held Monday at Riverside Memorial Chapel in Manhattan. Burial, said his daughter, will be on the Mount of Olives, adjacent to the Old City in Jerusalem.