Word of the pioneering rock ’n’ roll musician Little Richard’s death brought reflections and tributes from professional musicians on the South Fork and beyond.

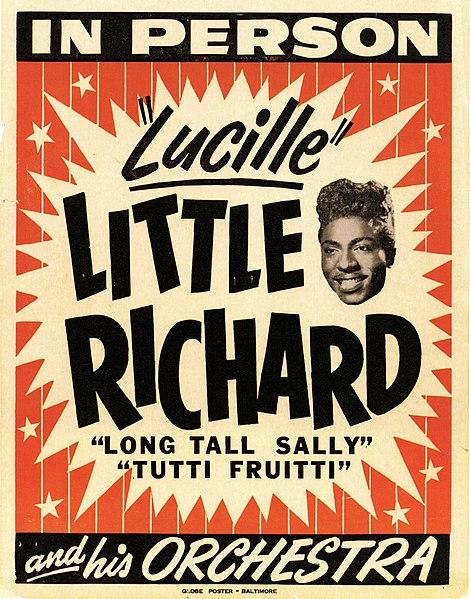

Along with Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Elvis Presley, Richard Penniman’s frantic, relentlessly electric and hard-charging vocal and piano performances, as heard on recordings like “Long Tall Sally,” “Tutti Frutti,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Lucille,” “Rip It Up,” and “The Girl Can’t Help It,” established a prototype for a nascent musical form that still reverberates around the world.

Born in Macon, Ga., Little Richard, whose biggest hits were recorded in the mid to late 1950s, was 87 when he died of bone cancer on May 9.

The writer David Browne, who lives on Shelter Island, wrote in Rolling Stone magazine that Little Richard’s music was “driven by his simple, pumping piano, gospel-influenced vocal exclamations, and sexually charged (often gibberish) lyrics.”

“His songs became part of the rock & roll canon,” Mr. Browne wrote, describing “a glorious mix of boogie, gospel, and jump blues.”

“He was really amazing,” said the guitarist G.E. Smith, who lives in Amagansett. “An obviously great performer, great piano player. He came out of that Southern piano style that had grown out of prewar boogie-woogie, the stride piano players and all that. When he got with those New Orleans musicians — Earl Palmer on drums — and made the records we know, it was exactly what he needed, and was just perfect. Perfect rock ’n’ roll.”

“From ‘Tutti Frutti’ to ‘Long Tall Sally’ to ‘Good Golly, Miss Molly’ to ‘Lucille,’ Little Richard came screaming into my life when I was a teenager,” Paul McCartney, who owns a house in Amagansett, wrote on Twitter. “I owe a lot of what I do to Little Richard and his style; and he knew it. He would say, ‘I taught Paul everything he knows.’ ”

“I had to admit he was right,” Mr. McCartney added.

“When the Beatles would go ‘Wooo!’ they got that from Richard,” Mr. Smith said. “He was a huge influence on [Mr. McCartney], they recorded a bunch of his songs, and played even more live. Paul was vocally very influenced by Richard, and I’m sure Richard’s left hand influenced his bass — he had a wicked left hand.”

Mr. Smith recalled performing with Little Richard in Manhattan around 30 years ago, a fund-raiser for the nonprofit Rhythm and Blues Foundation for which he served as bandleader. Performing on guitar alongside him were Steve Cropper, of Booker T. and the MGs, and Ry Cooder.

“When we did the run-through in the afternoon, Richard comes, and it’s an event. Everybody’s being respectful, he comes out, sits at the piano, and the first song was pretty straightforward. Then he goes, ‘Now we’re going to do “Lucille.” Great left hand lick. He looks up: ‘Guitar players, come here!’ We all went to the piano, he’s playing that left hand part. He goes, ‘I want you to play this!’ Ry said, ‘All three of us?’ ‘All three, and don’t play nothing else!’ That was really fun.”

The musician Steve Gorman, a founding member of the Black Crowes, was to play at the Stephen Talkhouse in Amagansett on May 16 (the performance, with his band Trigger Hippy, has been rescheduled). He shared his recollections of Little Richard on Facebook. He and Chris Robinson, the Black Crowes’ vocalist, were riding high in 1990, their cover of Otis Redding’s “Hard to Handle” having propelled them to stardom, when they met Little Richard in an elevator at the Continental Hyatt House, dubbed the Riot House, on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles.

“Immediately, he said, ‘Y'all must be in a band!’ Chris said, ‘Yes, sir! And we're from Georgia! The Black Crowes.’ Richard said, ‘Oh, y'all the ones that do the Otis song? I love that!’ He hugged us both and wished us well. The elevator stopped, he walked off. We were speechless.”

Mr. Smith’s first meeting with Little Richard, during a tour with Hall & Oates, was strikingly similar. “The first time I met him was in an elevator at the Hyatt House on the Sunset Strip. He was living there, it was on a Sunday, and he was on his way to the church to preach, so he was dressed. . . . I don’t think he went out without being dressed, but the makeup, the hair — he looked fantastic. Me and [the late bassist] T-Bone Wolk were with Daryl and John, had the day off, and had gotten in the elevator. It stopped, Little Richard got in. He looked at us, said, ‘You boys are musicians!’ ‘Yes sir, Mr. Little Richard, we are!’ ”

Mr. Smith, Mr. Gorman, and Little Richard would perform together in 2000 when Berry was recognized at the Kennedy Center Honors in Washington, D.C. “Richard walks into the rehearsal room, the night before,” Mr. Gorman wrote. “Says his hellos to everyone and then zooms in on Chris and me. He says, ‘Hello, Black Crowes — you probably won't even remember this but we met on an elevator years ago!’ Again, we're speechless.”

“I said, ‘Yeah, we remember . . . I can't believe you do!’ He says, ‘Y'all did Otis so proud, he was my little brother . . . I loved that man so much!’ And he sits at the piano and busts into [Redding’s] ‘These Arms of Mine’ . . . it sounds EXACTLY like Otis. I mean, he's CHANNELING OTIS REDDING.”

“It was mind blowing. The whole room is still. No one moves.”

“I glanced at [the drummer] Steve Jordan and we shared a ‘Holy shit this is actually happening’ look. Richard ran thru the form twice, then stopped. He said, ‘Y'all don't want any more of that, do you?’ laughing. Everyone in the room (G.E. Smith, Steve Jordan, [the Black Crowes], Don Was, the B-52s) yells ‘YES! More! Keep going!’ He laughs again . . . ‘No, no, that's enough, let's do what we're here to do.’ He killed us all. He knew it. And he left it there.”

“I originally went to D.C. excited and honored to shake a tambourine for Chuck Berry, but I left D.C. with my mind spinning over Little Richard and the fact that for an hour or so, I was standing next to a nuclear reactor. My entire body was buzzing the whole time he was in that room with us. Head to toe . . . on fire.”

“I can't even begin to imagine what it was like to see this man on a stage when he first showed up in the 1950s . . . but I can tell you that in the year 2000 it was still a visceral experience that goes well beyond my feeble attempt to describe. R.I.P. Little Richard. Many, many thanks.”