Dianne Blell photographs beauty: the beauty of ideal love, the beauty of the broken and ruined, and the beauty of art history. Her iconic series “The Pursuit of Love” and “Desire for the Intimate” mine Neo-Classical art, classical mythology, Moghul miniatures, and Hindu folklore, appropriating images and characters and restaging them in elaborate photographic tableaus.

Her most recent images focus on single objects — antique chairs, a miniature tree — often worn or damaged, presented in isolation against a black background as if “in a high-end antique auction catalog.”

Ms. Blell traces the direction taken by her photographic work to a lecture given by Tom Marioni, a San Francisco artist and founder of the Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA). She was a student at the San Francisco Art Institute in the early 1970s, and at first “I was uneducated,” she explained recently at her Bridgehampton studio. “Then I heard Tom talk about Conceptual Art and the importance of showing process, and for me it was as if the world had opened up.”

At that time happenings and performance art were figuring prominently throughout the art world. “All that was left afterward was the photographic documentation. And I thought, why not just address the camera immediately, and I started creating things for the camera alone.”

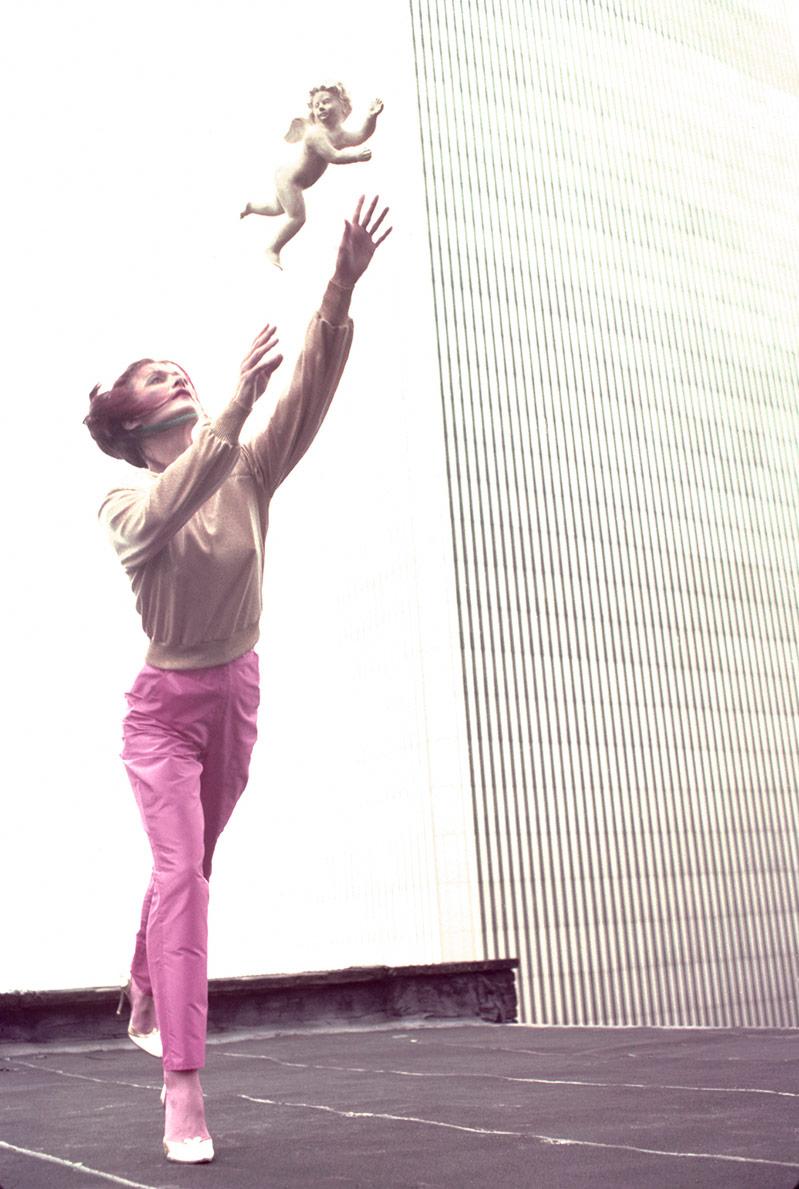

An early series from 1979, “Charmed Heads and Early Cupids,” consisted of nine photographs that referenced classical portraits of women from art history and fashion photography. Miss Blell, styled with fashions from the recent collections of New York designers, was the model for the images, which were accompanied by photo and styling credits.

In one image, “Pursuing Urban Cupid,” she is reaching toward the sky for a cherub suspended just out of her reach. Shot on the roof of her loft building in the financial district, she is set against open sky and the World Trade Center, which was less than 100 yards away. Another image, “Future Perfect,” shows Ms. Blell winged, like Cupid, with the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in the background.

Ms. Blell grew up in and around Chicago. It was in Wilmette, Ill., at the Convent of the Sacred Heart — “I was a very edgy kid, that’s why they sent me to the convent” — that her interest in the classical began to take shape. Early on the students read “The Odyssey,” “Beowulf,” and memorized poetry, and she discovered mythology. “To me that was the most wonderful thing, and it was full of images.”

The family moved to La Jolla, Calif., when she was a teenager, and it was at the Art Center in La Jolla, now the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, that she was introduced to a sophisticated art world. “Artists came there to teach or have gigs, and the curators gave shows to them. I met Larry Bell there, John Altoon, Sol LeWitt, Ed Kienholz.”

While taking classes at the San Diego College for Women, her parents divorced and she was left to her own devices. She moved to Los Angeles and worked as a secretary for a year and a half before deciding she wanted to see the world and took a job as a flight attendant for Pan Am.

Four years later, in 1970, she enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute and earned a B.F.A. and an M.F.A. in three years. “I wasn’t doing photographs then, I was trying to paint. That’s what you did. I didn’t know a thing about paint.” It was there that Mr. Marioni’s lecture set her on the path toward her mature work, and, after graduation, to New York City. In 1978, while still living in San Francisco, she found the loft on Cedar Street where she still lives and works when not at her house in Bridgehampton, which she purchased in 1993.

The series “Various Fabulous Monsters” and “The Pursuit of Love” were shown at Leo Castelli Gallery in Manhattan in 1983 and 1985 respectively. The sources for those works included paintings by Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Joseph-Marie Vien, Angelica Kaufmann, and other neo-classicists.

The art critic Donald Kuspit said of those two series, “Making us focus and rethink the style and meaning of the paintings and prints by restaging them as photo-tableaus, she breathes new aesthetic life into them.” Ms. Blell recreated the paintings by making the costumes and fashioning sumptuous sets in her loft from paper, cloth, and canvas.

“The sets were rooms. When they were finished and the photographs taken, I would have dinner parties in them. It was like eating in Pompeii.” The figures in “The Pursuit of Love” series are dressed, or not, as in the source paintings. Because the images were created in real time, before digital software was available, each scene was diagramed, and the models rehearsed and were captured with hundreds of Polaroid images before the final 4-by-5 shots were taken.

“I started out with the whole idea of the female form and desire in art history and the search for the ideal and beauty. I wanted to show that the camera in this day and age can translate old values and old romance and appreciation for classical pieces and history. I’ve been accused of being sentimental and romantic, as if I didn’t know what I was doing. I’m taking a camera and reactivating it as a human being.”

She continues to shoot with 4-by-5 film to this day, but the composite images in the “Desire for the Intimate” series, created between 2000 and 2008, were made by scanning separate 4-by-5 images and combining them digitally. She posed the models for Rada and Krishna individually and, as with the earlier series, created elegant sets based on Hindu miniatures. While the models are shown in intimate and sometimes erotic poses, “They never met. The people were Photoshopped into the sets.”

“I was always interested in medieval art and Moghul miniatures, and I was very interested in the human condition and the search for the ideal in humankind. I just locked in to Rada and Krishna as the great archetypal symbols of courtship.”

The series took nearly a decade to complete because of 9/11, which destroyed the first sets and other contents of her studio. Ms. Blell photographed the aftermath of the destruction from the rooftop of her building. Some of those images are now in the collection of the 9/11 Memorial Museum.

At first glance, Ms. Blell’s “Tragic Chairs,” part of her “Artifacts of the Contemporary” series and shown last month at MM Fine Art in Southampton, seem to be a radical departure. However, “Vessel,” like the “Tragic Chairs,” consists of a single object, a cheap plaster stage prop of an urn, set against a black background.

“It’s from 1983. It was in my first show at Leo Castelli,” she said. “It has always haunted me. I had accumulated a taste for these sort of broken, fractured ormolu and fragments and things that were part of other things. They have stories to tell.”

She had been “fiddling around” with images of her six aging antique side chairs for five years. For “Tragic Chairs,” the photographs of the chairs are slightly smaller than life-sized “so they would be abstracted from reality but would still invite the viewer to sit down.”

After the chairs were photographed with a 4-by-5 camera, the images were scanned and cut out by a computer controlled process, printed in reverse on the underside of a piece of Plexiglas, and mounted on a seven-foot tall sheet of black dibond, an aluminum composite material.

As a result of the printing, cutting, and mounting process, “the photograph becomes a physical entity. . . . As such, ruinous life-sized pieces become topographic reliefs in a spatial void unconfined by their original and quotidian contexts.”

What links the most recent work to the earlier series is what Mr. Kuspit called the artist’s “positive attitude to desire,” whether the desire of lovers or Ms. Blell’s romanticization of the damaged. She pointed out that such artifacts decay and often outlive us, full of “a shared gravitas and pathos of ephemerality, mortality, and obsolescence. Perhaps they can be construed as self-portraits.”