Is everyone else excited by the recent Saul Steinberg Foundation gift to the Parrish Art Museum? It is a collection of 49 works by the artist over four decades touching on most aspects of his creative practice.

Whether from yesterday or more than a century ago, it is thrilling to see works of art — made here or associated with artists who have long connections to the area — become part of the permanent archives of local institutions. There they can be shown in a wonderful context, whether at the Parrish Art Museum’s potato barn on steroids nestled in a field of native grasses in Water Mill, at the quirky antiquity of Guild Hall, or at a number of historical societies, artist homes, and other nonprofit spaces like the Dan Flavin Institute in Bridgehampton.

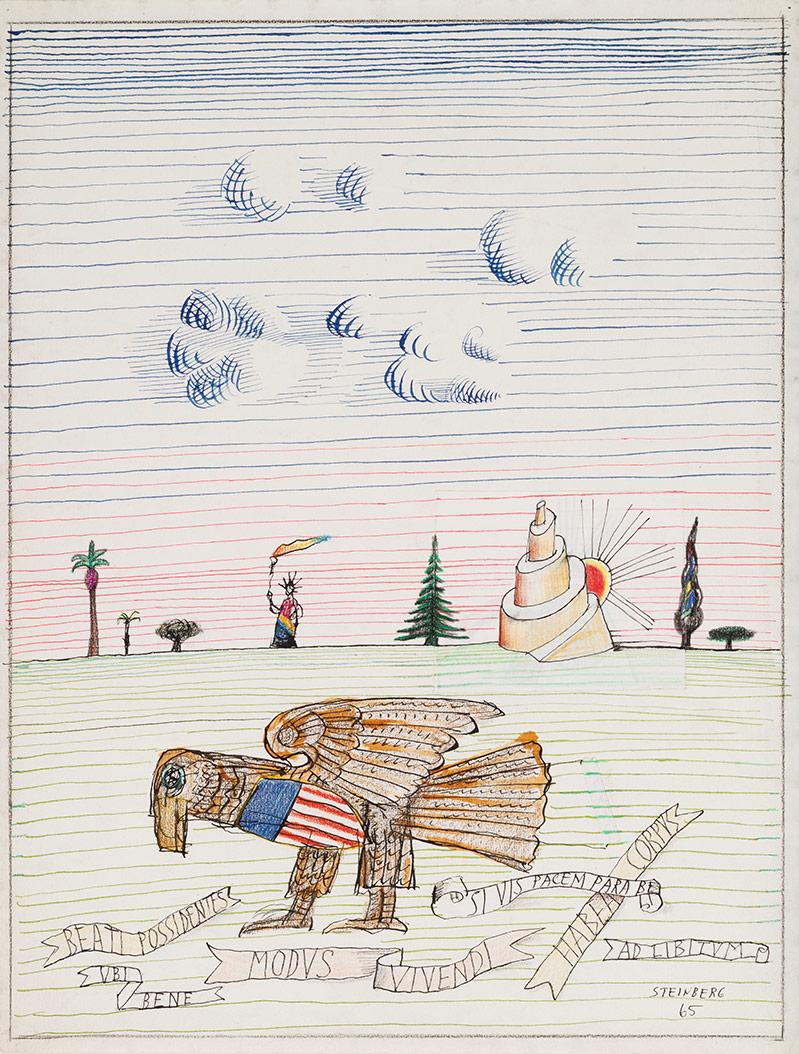

The Saul Steinberg Foundation is the latest to notice and has chosen a varied and broad survey of drawings and objects from 1945 to the 1980s to donate to the museum. The artist arrived in the United States in 1942 as a refugee from Europe, originally from Bucharest, Romania, and found his way out here, purchasing a house on Old Stone Highway in 1959. He died in 1999.

In Europe, he had studied architecture and contributed cartoons to an Italian humor newspaper. In fact, it was the editors of the publications that had already started including his drawings in their pages who interceded to help him enter this country.

Steinberg was famous for nosing out the absurd in daily life and putting it on full display so that we too could witness it. Two standout pieces from memory that were inspired from the local landscape were his take on the Flanders Big Duck, which appeared a few times in his work, including a New Yorker cover in 1987. Although the cars are fanciful in that particular composition, there is another, more surreal take in which the store built in the form of a colossal duck sits in a pond and the automobiles that race beside it become other flora and fauna of the East End landscape, such as a fish, a potato, a carrot, and a bird.

“Amagansett Barricade,” a drawing he made of workers blocking Main Street and their Labrador retrievers popping up all over, is exaggerated but funny, and true in its own way.

There are not too many direct references to the East End in this particular grouping, a nod to the water in his landscapes or a portrait or two of friends from here such as Costantino Nivola notwithstanding. But the “Amagansett Post Office” lithograph, with its identifiable modest box shape (a flag on an exaggerated three-story pole placed out front) and the artist’s own reference to it in its title, is true to the site and the artist’s vision of it. Another dog pops up in the scene, barking from the back of what appears to be a pickup truck. There are other cars driving by, puffy clouds hanging low in the sky, and what could be a rainbow in the distance. Is this paradise?

Another untitled drawing in the collection worked on from 1980 to 1990 touches on local topography: the flat, groomed farm fields that set up a patchwork as they recede to the water. There are plows making regular furrows in the topsoil, but houses are already encroaching — even two tiny ones in the middle of the fields with pools attached — much as they have in the decades that followed. Steinberg seems to capture the spirit of the repurposed architecture that people dragged down to the beach to make shelters for themselves in the postwar period. It’s a delight to see the area through his satirical but affectionate gimlet eye.

One of the fascinating things about this artist — and there are many — is how his vision shaped his art in ways that made him singular in the very serious years he lived in. It wouldn’t be until the late 1950s and 1960s that Neo-Dada would make humor and irony in art mainstream, but he was already well in the thick of it, even if his contemporaries and his wife, Hedda Sterne, were firmly planted in the grand intellectualism of the New York School. Yet he was neighbors and friends with Harold Rosenberg, an art critic and crusader for the Abstract Expressionists, with whom he met in “a daily symposium,” according to the Parrish.

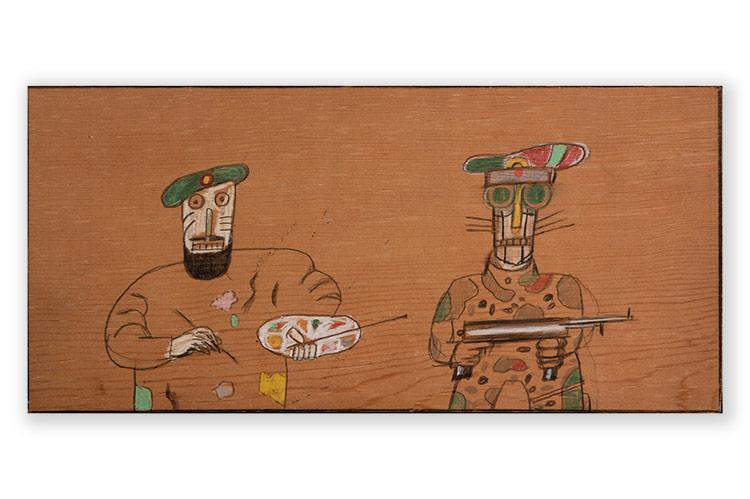

The collection here has its curiosities. A printed fabric with his “View of Paris” joins wallpaper of trains and the Paris Opera as subjects, and a long scroll of hand-printed ink on cotton with a composition called “Aviary” has fanciful birds placed throughout. These works were mostly completed around 1950. Two cartoonish faces are drawn in pencil and painted in oil on the backside of a cut-up primed canvas. While seemingly casual and offhand in nature, these works, which range in time from the 1950s to the early 1970s, may stand for something else inherent in Steinberg’s work. He often revealed the inverse, making a spectacle of the overlooked.

The sculptures include a carved wooden pencil case and a low-relief piece in carved wood with a colored pencil mounted on it and an etched piece of tin that seems to be a stand-in for a ruler. Steinberg used rubber stamps of his own design freely throughout his work, and the collection here is no exception. He made stamps of small figures who often populated his landscapes and other objects he could repeat at will. There were also regular uses of fanciful seals and certifications, likely inspired by the stamps in personal identification papers he and his fellow refugees were forced to carry and present to totalitarian government officials they fled.

The idea of “building it and they will give” seems to be working. The Parrish has announced a number of major donations since it opened its new space, which has an entire wing devoted to displaying its permanent collection. Guild Hall, too, has placed renewed focus on its collection through a thorough cataloguing, photographing, digitizing, and now regular exhibitions.

We can only hope and anticipate that these efforts will bear even more fruit. With so many collectors buying art as an investment and putting masterpieces in vaults until the value escalates, it is wonderful to see artworks emerge from their hermetically sealed, environmentally controlled packing crates and breathe for us again. The Parrish’s collection will be on view in the museum well through 2021.