In many ways, the history of 303 Gallery is the history of the past few decades of art in America, and particularly of that halcyon mid-1980s moment from which so much of today’s art world still descends.

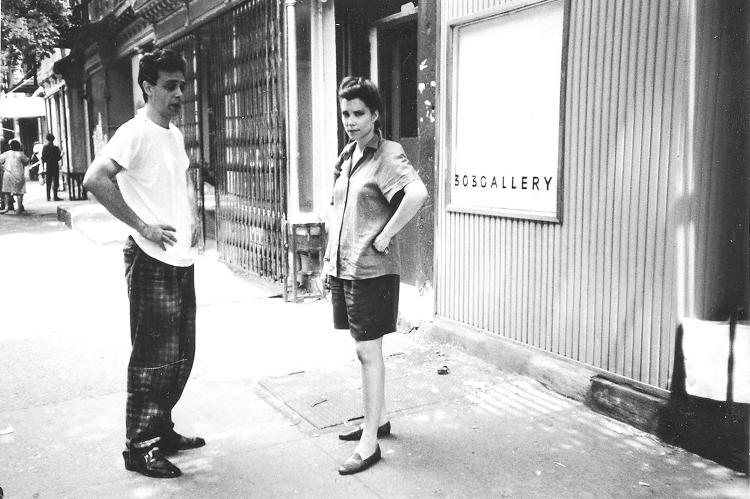

The gallery, which began less as a business and more as a manifestation of one woman’s instincts, passions, and intellect, has become a model of professional success. With each new location, from 303 Park Avenue South to the East Village, to SoHo, and finally to Chelsea, the gallery was a pioneer leading the evolution of those neighborhoods into art destinations, and brought so many along with it.

That woman, Lisa Spellman, may be known locally more for her activities in Montauk that revolve around other enthusiasms — surfing, hiking, and biking — but she is an international phenomenon, whether people here are aware of it or not.

It is to her credit that she is equally at home in the center of powerhouse art fairs such as Art Basel, the Armory, and FIAC as she is picking up corn at Balsam Farm and fish at Gosman’s Dock for dinner. But this summer, her gallery turned 35, a significant milestone and accomplishment, and she decided to celebrate.

A show marking the gallery’s history accompanies a 450-page catalog that delves deeply into the artists and their shows, which began in 1984 and should continue for many more. Ms. Spellman was a student at the School of Visual Arts when she rented a loft for $470 a month on Park Avenue South to live and then work in as she began planning a gallery space there.

The grandniece of Cardinal Francis Spellman, who was the archbishop of New York, Ms. Spellman said he died when she was very young and her immediate family was not religious. “All I remember of St. Patrick’s Cathedral was the incense and all of the mystical stuff.”

Her great-uncle was a stamp collector. A museum in Massachusetts was named after him. “He said something really great about stamps,” she said as she searched her memory. “Stamps are miniature documents of human history. They are the means by which a country gives sensible expression to its hopes and needs, its beliefs and ideals.” Other than that, she said, “My family has zero interest in art.”

New York awakened her own interest. “When I moved to the city, I fell in love with photography and had that Berenice Abbott moment.” She enrolled in the School of Visual Arts and worked hard to build a portfolio while also holding down three jobs, including evenings at nightclubs.

“We developed and printed our own film then,” she recalled. “I would spend 12 hours in the darkroom, then go to work.” In winter, when the sun set at 4:30, she found that weeks would go by without her seeing daylight. “After three years at S.V.A., I realized it wasn’t that healthy of a life.” It didn’t help that her instructors were old school. “I loved them, but they didn’t know anything about contemporary photography. They didn’t know who Cindy Sherman was, and this was in 1978.”

It was a period when the club scene and the art scene often merged at Max’s Kansas City, CBGB, and Mudd Club. “There were galleries opening every second. I was younger than the scene, but exposed to it and observed it.” At the age of 24, it never occurred to her that opening her own space was something she couldn’t or shouldn’t do.

Studying photography “was a great way to train the eye. It is such a specific discipline in its way of seeing things. . . . Back in the ’70s and ’80s, photography was a million miles away from the art world, but there were some intersections.”

The exhibition “303 Gallery: 35 Years,” on view there through Friday, Aug. 16, is an assemblage of artists who have shown throughout those years, a list that includes Doug Aitken, Kim Gordon, Dan Graham, Mary Heilmann, Larry Johnson, Karen Kilimnik, Nick Mauss, Kristin Oppenheim, Richard Prince, Collier Schorr (who rose from intern to director to artist), Stephen Shore, Sue Williams, and many others.

For someone who has not yielded to commercial pressure, even as some of the gallery’s most notable artists have moved on to larger art dealing enterprises, she has been wildly successful at keeping a core roster of artists happy and well fed. The show is chronological, tying the artists to where they fit in in the gallery’s history. “We tried to find examples as close as possible to when we first showed an artist.”

Many of the artists contributed essays to the catalog, which offers a fully comprehensive chronology encompassing shows of work by Vito Acconci, Jeff Koons, Christopher Wool, Robert Gober, Rirkrit Tiravanija (the artist cooked Thai food in the gallery), Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Liz Larner, Charles Ray, and countless others. The book is from the gallery’s imprint 303inPrint, which has been undertaking artists books for the past few years.

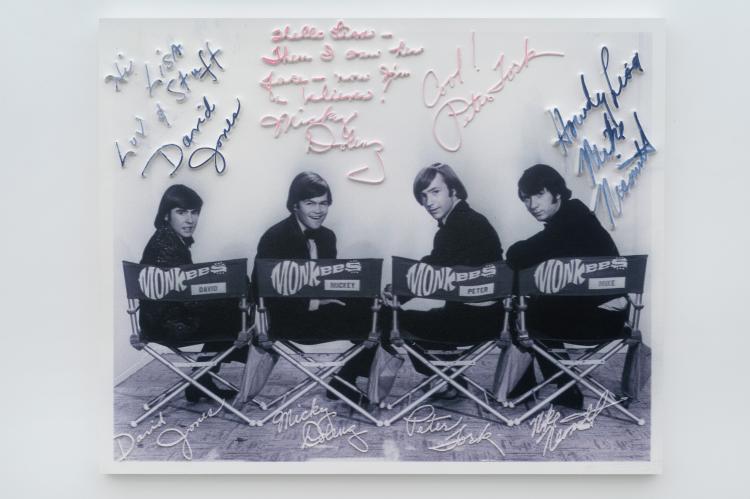

Mr. Prince, who was married briefly to Ms. Spellman during a six-year relationship (she is now married to Tin Ojeda), contributed to the catalog both an essay and a painting based on an autographed photo of the Monkees that Ms. Spellman had from her childhood. “Untitled (Monkees)” recreates the image and raises the lettering on the individual notes and signatures made by the group. “It was a photograph I got when I was 6 or 7. Who wasn’t obsessed with the Monkees?”

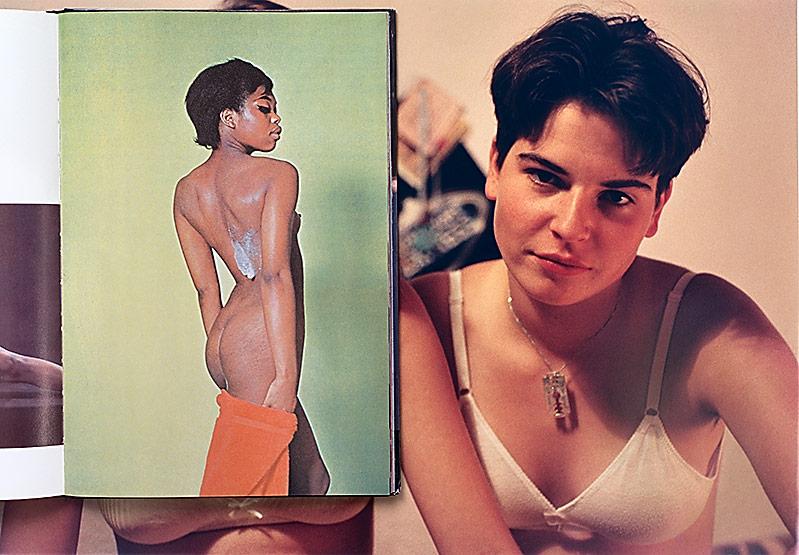

In his essay, broken down into eight “memories,” Mr. Prince reveals the hip chaos of their younger years. He was couch-surfing and “recovering from anxiety and mental fatigue,” he said. “She was living in the middle of her third show. . . . The space was an open loft and she walled off her bedroom, which was in the middle of the ‘gallery.’ ” He showed work there as himself as well as under the pseudonym John Dogg.

He introduced her to Jeff Koons, and she showed one of Mr. Koons’s early “Equilibrium Tanks.” That show’s checklist, part of this current exhibition, has the price set at $3,500. At the time, she wanted to buy it with three other people, but couldn’t afford it, she said. Mr. Prince recalls in his essay waking at 4 a.m. with light coming in from outside. “For a couple of minutes, on the way to the bathroom, the tanks were all mine.”

Ms. Spellman’s last move — to Chelsea in 1995 — has stuck. From an initial gallery on 22nd Street, she bought a garage on the end of 21st Street, across from the Hudson River, and tore it down to build her dream space, a columnless two-floor gallery and work environment. It has been open for three years.

Although some galleries are now leaving Chelsea, the way she fled other neighborhoods in her past, she plans to stay put. “If it got to a point where no one was coming to the gallery anymore, we would have to re-evaluate . . . but we feel really comfortable here. There is nowhere I could go where I could build such an amazing space. We may not like what’s going on around us, but that’s just the state of New York right now.”