For a couple of years after graduating from high school, Joe Bradley hung around his hometown of Kittery, Me., painting houses, doing odd jobs, and drawing. “I sort of cut my teeth on the underground comics of the 1990s, because that was what had trickled down into my head as a teenager in Maine. I hadn’t gone to too many museums at that point.”

Today his paintings hang in museums, among them the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo. The turning point came in the mid-1990s, when Mr. Bradley paid a visit to a friend who was studying at the Rhode Island School of Design. “I thought, yeah, this looks like fun.”

He is now represented by the Gagosian Gallery, the Almine Rech Gallery in Paris, and Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich, where a solo show of his paintings and drawings opened on Saturday. He began the paintings in New York City, but relocated with his family to their Amagansett house in March after Covid-19 hit, and finished them at the Elaine de Kooning House in Northwest over the past three months.

He and the gallery worked together over FaceTime to install the exhibition. “I had some ideas about which paintings should go next to which,” he said, “and it looks online more or less like I was hoping it would look. It’s a bummer not to be able to be there and celebrate it.”

Success came relatively early to the laid-back Mr. Bradley, yet he still seems almost bemused by it. “It just took shape without a lot of hustling on my part. I was hustling in the studio, I was serious about working, but those connections happened pretty effortlessly.”

His adoption by a number of important galleries hasn’t fazed him. “I’ve never had a gallerist bug me to make a particular kind of work, or to make more work, or anything. Most of the pressure is self-imposed. On the one hand, it’s a really brutal self-inquiry that you do on your own in the studio, and then you put it out there and wait. It’s like a message in a bottle. I’m not sure it’s totally healthy as a lifestyle.”

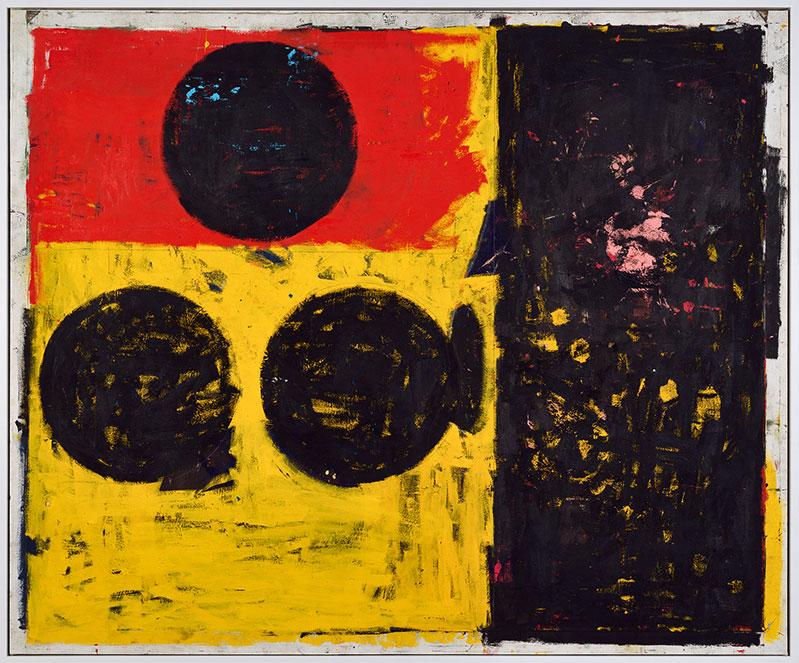

Mr. Bradley’s 20-year career has been marked by frequent stylistic shifts, ranging from almost minimalist geometric works, to black silhouettes of dancing figures, to dense, expressionistic abstract oil paintings, to simple, almost childlike drawings and sketches.

While art wasn’t a part of his family life, his parents were encouraging about his attending art school, in part because they thought he had talent. Before R.I.S.D., “I knew Picasso and Andy Warhol and that’s sort of it,” Mr. Bradley said. He went to the college’s highly regarded museum and spent a lot of time in the library, “giving myself an art history education.”

As a young painter he looked at the career trajectories of certain artists he liked and decided that stylistic consistency wasn’t for him. A Robert Smithson retrospective at the Whitney Museum was a game changer. “I remember thinking it was totally mercurial, the way his practice changed almost from year to year. You could go from his figurative, quasi-religious paintings of the early 1960s to the Spiral Jetty in a decade.”

Among his college mentors were David Hornung, a color theory teacher whose influence can be seen in Mr. Bradley’s "Modular Paintings," and Dike Blair, who was living and working in the city while teaching at the Rhode Island school. Mr. Blair put Mr. Bradley in a group show in Boston soon after his 1999 graduation.

Kenny Schachter, an artist, writer, and dealer, saw that exhibition and offered the artist a show at his West Village gallery in 2003. That led to numerous group shows, a 2006 solo exhibition at PS 1 Contemporary Art Center, and the Whitney Biennial two years later.

It was at PS 1 that he first showed his modular paintings, which consist of monochromatic rectangles assembled in anthropomorphic shapes. Those works investigated the ways colors exist in relation to each other, while at the same time suggesting architectural or human forms. Unlike much of his other work, that series called to mind such color field painters as Ellsworth Kelly and Barnett Newman.

Two years later, a show at the CANADA Gallery on the Lower East Side featured his Schmagoo paintings. Those monumental works, executed in grease pencil on canvas, featured simple, almost doodle-like sketches of the Superman logo, a stick figure, a cross, and a fish, among other images more reminiscent of cartoons or the late paintings of Philip Guston. “I came across the word ‘Schmagoo’ in a book about New York drug culture. It was used as slang for heroin. The word stuck with me.”

His more recent works, which feature overlapping colors and shapes, are painted on canvas laid on the floor, sometimes incorporating footprints and detritus from the studio. The Zurich show, with 10 paintings and 46 drawings, reflects his growing interest in drawing. Some of the paintings include animalistic archetypes, human faces, and simple everyday objects.

Mr. Bradley first came to the East End in 2012, spending the summer with his wife and children as one of the first artists in residence at the Elaine de Kooning House. Two summers later he had a show at the Karma Gallery in Amagansett. “It just felt really nice to be here and close to the ocean, so we bought this old house” in the hamlet.

The house doesn’t have a studio, so after arriving in March he called Chris Byrne, who owns the de Kooning house, to ask whether he could finish the work for the Zurich show there.

“The scale of the studio there is really right for those paintings. I’m aware of being indebted to the New York School in many ways, to Elaine’s work, and to Willem de Kooning’s work. I think that lineage is cool, and has a resonance with being here.”

The Bradley family will remain in Amagansett for the foreseeable future. The children are now 16, 10, 6, and almost 1 year old. The oldest will attend school over Zoom while the two middle children will be home-schooled.