Michi Itami has worked in a variety of mediums -- printmaking, ceramics, painting, digital photo collages -- but as an artist and teacher, her attitude is consistent: “If you just listen to what they say you have to do, you don’t get anywhere. If you step outside of the box, if you just think creatively, there’s so much you can do.”

As a Japanese-American woman born in 1938, Ms. Itami has had to step outside the box throughout her life. After Pearl Harbor, she and her parents, who were first generation immigrants to the United States, were interned at Manzanar in the California desert.

Her father, Akira Itami, was released, however, after he volunteered for the U.S. Army. His work deciphering Japanese military communications and gathering intelligence data earned him the Legion of Merit for exceptional service.

After the war, he was posted to Japan as an officer in the American-led occupation, and went on to serve as head interpreter at the Tokyo War Crimes Trials. In 1947, Ms. Itami and her mother, Kimi, joined him in Japan, where they lived for the next three years.

While there, her father “saw that I was artistic, and he hired people to teach me drawing at home,” she said during a Zoom conversation from her Sag Harbor house. “Those teachers were so happy to make any money at all. War-torn countries are not lovely. It was sad.” Sadder still, when she was 12, her father committed suicide.

“He got all kinds of medals for his service in Tokyo. It was very tragic. I think he felt misunderstood.” Ms. Itami’s parents were kibei, or U.S.-born Japanese-Americans who were educated in Japan.

“I think that being a kibei . . . was difficult for him,” she told The Japan Times in a 2005 interview. “Nisei [second generation Japanese-Americans] did not trust kibei because they were so different from themselves. And he was alienated from other kibei because he was too intelligent to believe the propaganda of the Japanese military government at the time.”

Ms. Itami returned to Los Angeles with her mother, and in 1959 she earned a degree in English literature from U.C.L.A. After doing graduate work at Columbia University in Japanese and English literature, she returned to Japan for a year on a Fulbright grant to study ceramics, and went on to earn an M.F.A. in ceramic design from the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1971.

Her first teaching job was at Hayward State University in California, where she met Misch Kohn, who is widely credited with reinvigorating the field of printmaking in postwar America. He became her mentor, and from the early '70s on, she created a body of prints that has been widely exhibited and collected.

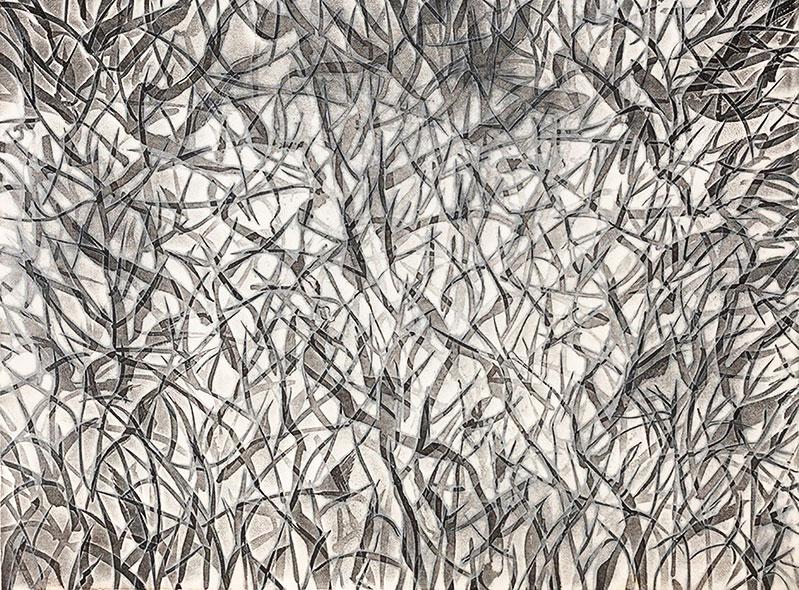

Her prints, while abstract, range from almost minimal geometric patterns to looser, more gestural compositions that echo landscape elements. Of one such etching, “Kusamura,” from 1975, she said, “This one looks like grass growing. I prefer drawings that are very loose. If Abstract Expressionism had never happened, I don’t think I would have been an artist. The idea that you can make a stroke and it means something is so important, but it doesn’t have to be a depiction of anything.”

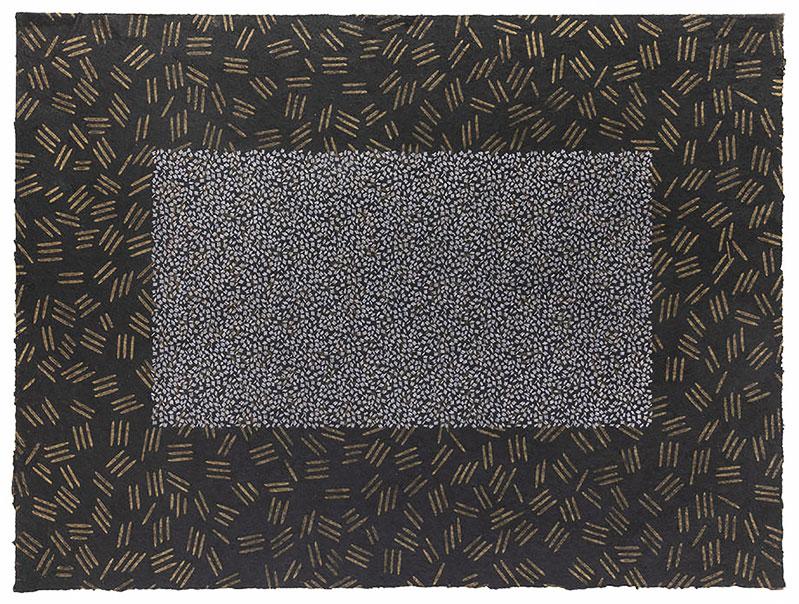

Two 1982 prints on rice paper, one an etching, the other a silkscreen, consist of a rectangle set within a larger rectangle. Seen close up, the outer pattern is revealed to be an enlarged version of the inner pattern, which itself consists of groupings of three tiny lines.

After teaching at Hayward and then at the San Francisco Art Institute, Ms. Itami moved east in 1988 to teach at the City University of New York. She taught at CUNY for more than 20 years, becoming head of its M.F.A. program, and receiving, in 2004, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Caucus for Art.

“I loved City College,” she said. “What was great about it is that you didn’t have to be privileged to go there. It was for immigrants and people whose parents never went to college. I love that part of it.”

“I really like teaching something that is new for people," she added. "It helps them develop as human beings. I do think art has this wonderful capacity to help you find your inner self, and that’s a very important thing.”

While Ms. Itami’s prints are abstract, her paintings and watercolors run the gamut from abstraction to representation, often reflecting the influence of landscape. A quantum shift in her practice happened in the early 1990s, when “the ability of the computer to combine and re-size images inspired me to make a series of works dealing with my family.”

One iconic work from that period is “The Irony of Being American,” a large computer-generated four-color lithograph in which three photographs of her father, one at 16 in Japanese dress, one at 25 in a suit and tie, and one as a soldier with an American flag draped over him, are superimposed over a photograph of Manzanar by Ansel Adams. “My father was an amateur photographer, and I had these wonderful photographs," she explained. "His life was a tragedy, and I felt his story needed telling. It’s not easy to be a minority in America. It’s also not easy to be a woman.”

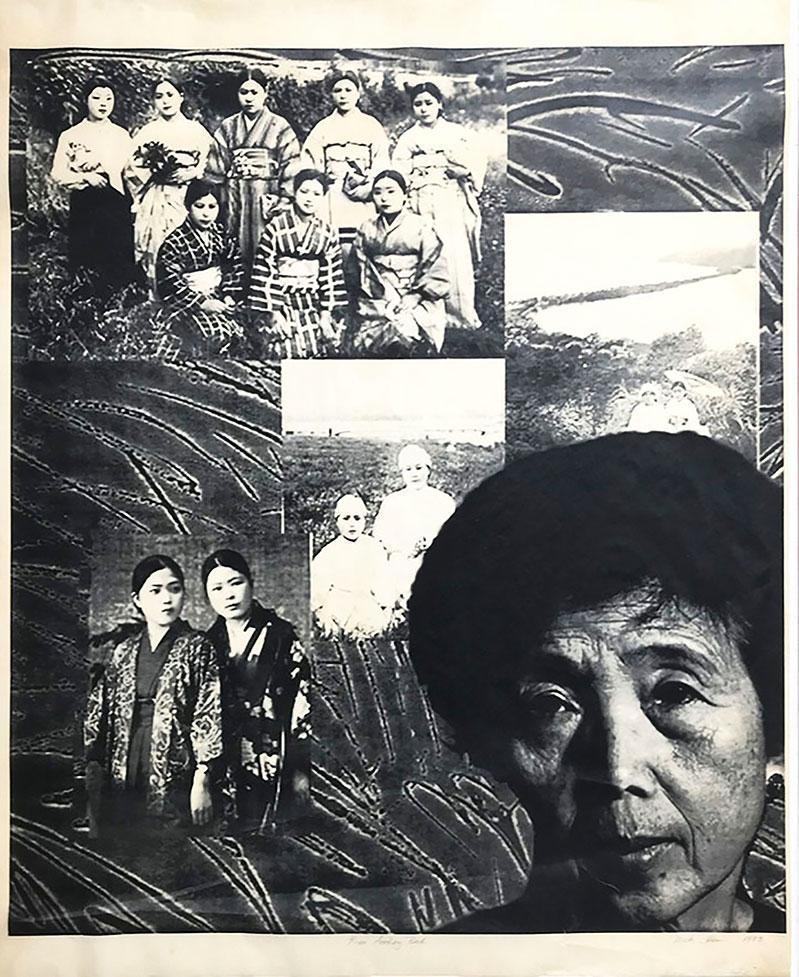

Another work from the series is “Kimi,” which is devoted to her mother. Several of the images are from her mother’s childhood on a pineapple plantation in Hawaii, which was difficult. Kimi eventually went to nursing school in Japan and later became a nurse in Los Angeles. “My mother was a wonderful human being, and she encouraged me,” said the artist, to persevere in the face of obstacles.

Ms. Itami’s path, after running through Los Angeles, Manzanar, Tokyo, Berkeley, Minnesota, and New York, led to Sag Harbor in the late 1980s, when she visited friends who were renting there. In 1991, she and William Hess, an architect and her former partner, bought the house where she now lives full time.

After retiring from CUNY, she decided to move to Maui, and she and Mr. Hess divided their time between Hawaii and Sag Harbor until they separated in 2017. “I love it here,” she said, especially that the village is an artists’ and writers’ community. "I love the country, I love landscapes, and it keeps me making work.”

Creativity continues to run in her family. Her daughter Sarah is a writer, now living in London; her daughter Naomi is a musician and opera singer who lives in Brooklyn.

Three of Ms. Itami’s prints will be in an exhibition set to open in May at New York’s Museum of Chinese in America. Titled “Godzilla vs. the Art World, 1990-2001,” the show examines the work of Godzilla, a collective of activist Asian and Pacific Islander-American artists. Ms. Itami was a member in the '90s.

She was also a member of A.I.R., an artist-run gallery founded in 1972 to highlight the work of female artists. She had a solo show there in 1991 and a print retrospective in 2003. Her work is in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Oakland Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the University Art Museum, Berkeley, and the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, among others.