"How about this?" Bill Henderson wrote in an email, offering up a summation of his extraordinary accomplishments over five decades.

"Young man wants to write great American novel. Spends years on writing it and is rejected by commercial publishers. Hurt badly, he issues novel himself to tiny triumph. Wants to help others in similar pickle and publishes 'Publish It Yourself Handbook.' Big sales, starts Pushcart Prize to offer pep to other writers squashed by conglomerates. Forty-seven years later his annual anthology still gives him the joy of empathy, which he would never have experienced if that first novel was not rejected. Pain to caring: the key."

Happy 50th, Mr. Henderson, the founding editor of the Pushcart Press, which he started in 1972 in a studio apartment in Yonkers. Here's to manhandling the publishing industry behemoth with the ease of a nightclub bouncer.

It all began with anger. Righteous anger, he emphasized.

"When you do good work and the world ignores you -- and I've never, ever forgotten that -- when the money people take over the commercial publishers, a lot of people are crushed. I was crushed. I had worked hard at this book. I told the truth," Mr. Henderson said, sitting in his Springs home last week, his old Puerto Rican rescue mutt, Mr. Charles, at his feet.

So, in 1970, seven drafts and seven years after completing his debut novel, "The Kid That Could," which, like any half-decent writer, he had worked on in Paris, in the attic of a Left Bank hotel, he published it himself under the pen name Luke Walton.

The novel, which was a part-fantasy, part-autobiography, entirely irreverent account of the adventures of a 14-year-old boy, was published with the help of an uncle in New Jersey who had a small printing press. It received mixed reviews and sold about 500 copies. "I lost a bundle but it saved my soul," Mr. Henderson said.

For, what happened next was an almost prophetic revelation: Book publishing is a surprisingly simple business. "You get a good book, print it, put it out for publicity, and wait for orders."

The Pushcart Press was born. "The Publish It Yourself Handbook," its first book, was a remarkable anthology of essays by literary legends like Leonard and Virginia Woolf and Anais Nin, who offered D.I.Y. publishing advice to other aspiring authors. The book sold 75,000 copies, was reviewed widely, and heralded a success.

Its monetary gains sparked yet another idea: The Pushcart Prize, a yearly collection of fiction, essays, and poetry "to celebrate the undercelebrated," selected from small presses and literary magazines. The first edition was released in 1976, and by the second volume, a year later, The New York Times Book Review proclaimed that it was "perhaps the single best measure of the state of affairs in American literature today."

"Anger has fueled me for 50 years. And I'm still mad," Mr. Henderson said. Marked-up submissions for the 47th volume of the Pushcart Prize, which will be out at the end of the year, were scattered around his coffee table.

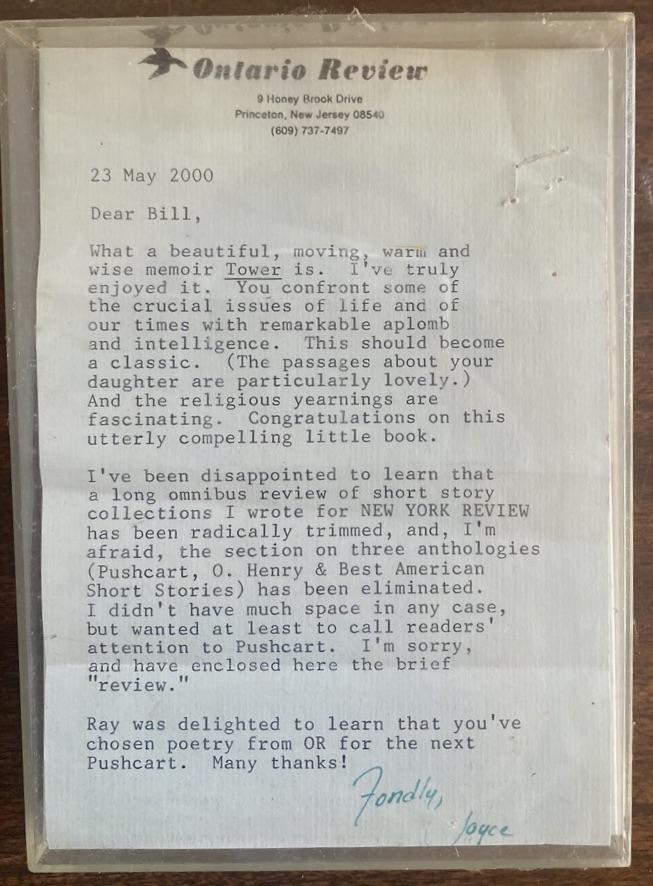

It was in 1981, inspired by Henry David Thoreau's retreat to write in the cabin on Walden Pond, that Mr. Henderson left New York City, where he had once worked as an associate editor at Doubleday, and set up his home in the Springs woods, with his now-wife, Genie Chipps, a fellow author. In the back garden, he built a minuscule (about 8 by 8 feet) wooden shack -- Pushcart's HQ -- stuffed to the rafters with congratulatory letters, including one from Joyce Carol Oates, books, manuscripts, literary memorabilia, and family photos of his wife and their beloved daughter.

"But it's not about me," he said, a few times over. Then who?

"I have an awful lot of help. And this is really important for your tape recorder or whatever recorder that thing is," he said pointing to my iPhone. "Pushcart survives with tons of help. It's not just me. I'm the secretary."

Every fall, Mr. Henderson, 81, sends out about 800 to 1,000 letters to small presses and publications around the country, inviting them to send in their nominations. In addition, around 200 contributing editors to the Prize also make their suggestions. Then he and other seasoned readers go through the "immense slush pile of about 10,000 pieces of stuff."

"Do you receive submissions by email?" I asked.

"No!" Daggers flew from his eyes. "The U.S. Postal Service."

So, the very analog Pushcart Press's official address is a Wainscott post office box. Why?

"Because who would take you seriously if you published a literary journal from a famous resort town? You can't publish one from East Hampton. Or from Atlantic City. But nobody knows where Wainscott is. It could be anywhere. And they're good people at the post office. They take care of me when the onslaught of stuff is coming in."

The onslaught over the years has come from Raymond Carver, Mary Gordon, Wally Lamb, Amy Hempel, Charles Baxter, Junot Diaz, Andre Dubus, Anne Carson, John Gardner -- all literary stars now, but they were once unknowns whose work was printed in small publications and heralded by the Prize. Other heavy hitters such as Frank Conroy, Richard Ford, Ms. Oates, Paul Engle, and George Plimpton have written introductions to the anthologies over the years.

The Pushcart Prize has evolved as a literary institution, a beacon for unsung work, and one that Mr. Henderson said only improves each year. In 2020, he won the Award for Distinguished Service to the Arts from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

In the foreword of this year's Prize, he wrote: "Because finally we writers have found that we don't need the approval of the bean counters to create what is beautiful, disturbing, and true. We are locked out of the money apparatus and have emerged free. The Pushcart Prize is the result of that freedom."

Ultimately, this is a story almost Shakespearean in scope. The backdrop is the literary world, a place full of darkness and epic greed, of dreams and sacrifices, soaring hopes and plunging despair. From within emerged a visionary, a righteous disruptor, an antihero who somehow pulled off an extraordinary feat of literary comeuppance.

Here's to the next 50 years.