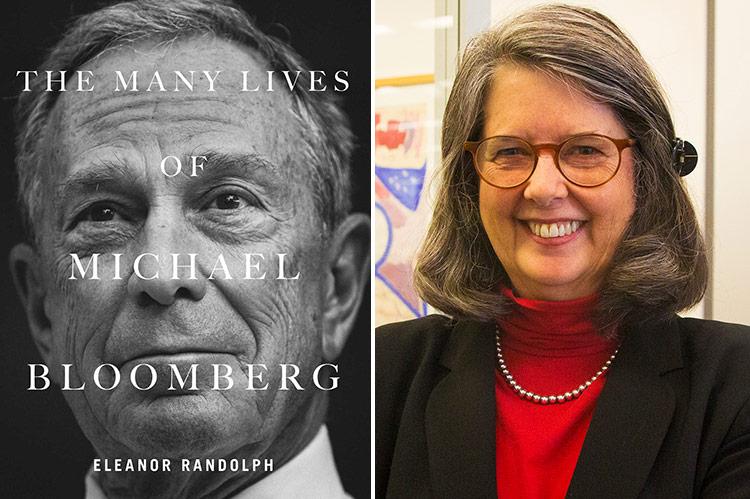

“The Many Lives of Michael Bloomberg”

Eleanor Randolph

Simon & Schuster, $30

Whether you liked him or not, Michael Bloomberg was a larger-than-life mayor, on par — as has often been noted — with legendary figures such as Fiorello La Guardia and Ed Koch. During Mr. Bloomberg’s New York City reign, not a day went by when the front pages didn’t cover a slew of initiatives hatched by his fertile administration. He had New York’s back, even his enemies would admit, though invasive policies such as stop-and-frisk often enraged his constituents.

New Yorkers crossed paths with him everywhere: on the subway, strolling the streets, at the upper Madison Avenue coffee shop he frequented. I wouldn’t have been surprised on dialing the city’s 311 complaint line if Mr. Bloomberg had picked up, such was the sense of his ubiquity.

The former New York City mayor has no greater fan than the journalist Eleanor Randolph, who has exhaustively catalogued his achievements in her new book, “The Many Lives of Michael Bloomberg” — from his youth in Medford, Mass., and his Johns Hopkins and Harvard education, to his grooming at Salomon Brothers and the scrappy rise of Bloomberg L.P. into the behemoth it is today. You would have had to be living in another dimension not to know that Bloomberg terminals transformed Wall Street from an old-boys game of “who you knew” into a playing field that gave those who armed themselves with information the team advantage.

The chief focus of the book, however, is Mr. Bloomberg’s first unlikely mayoral run and his three successful terms. Throughout the book, Ms. Randolph, a former member of the New York Times editorial board and a prolific freelance journalist, spares no opportunity to emphasize that the man himself is supernaturally confident, rich, brilliant, and a salesman par excellence, not to mention Jewish and short. Even Mr. Bloomberg’s failures — such as his efforts to reform public education — are cast as inspired ideas that either came before their time or were at least an indicator of his bold creativity.

Unauthorized biographies usually suffer from a lack of depth, and “The Many Lives of Michael Bloomberg” is no exception. If you read New York newspapers, you won’t learn much about the man from Ms. Randolph’s treatise that you didn’t know before. Though she claims that Mr. Bloomberg’s friends and associates were a help to her in this narrative, the book has the feel of repurposed press releases. For all they add to the mix, the quotes might have just as easily been lifted from existing articles as from fresh interviews the author conducted herself.

The biography essentially moves from issue to issue in a vague chronology — the campaign, public health, education, prison reform, philanthropy, etc. A Google search of these subjects might yield the same net result in less time. But the most tedious aspect of the construction of this narrative is how often Ms. Randolph ends up essentially starting from scratch and repeating herself.

Again and again, we hear that Mr. Bloomberg speaks ill-advisedly at first and apologizes later, hires the smartest people he knows, favors risk over caution, works hard, values loyalty, and focuses on details that might be diagnosed as O.C.D. (my words) on a less successful candidate. We get that he’s among the richest and most philanthropic men we can possibly imagine, without reading it yet another time. Oh, and did I mention he’s short? Five feet eight inches, in case you missed it the first time.

That Michael Bloomberg was a data-driven mayor comes as no surprise, given that his business empire was built on technology. Ms. Randolph notes that as mayor he often used that data to solve seemingly intractable problems. A personal favorite were the reports picked up by 311 of the overwhelming smell of maple syrup that enveloped the city one day in October of 2005. Anxious New Yorkers feared it was a deadly cloud of poison gas released by terrorists.

Springing into action, the city’s experts mapped the locations of the 311 callers, charted the winds, crosschecked the data, and confirmed that it was a New Jersey factory fabricating a mock maple syrup — delighting the mayor. “Given the evidence, I think it’s safe to say that the Great Maple Syrup Mystery has finally been solved,” he joked, praising the “smelling sleuths” who had cracked the case.

No proposal crossed the mayor’s desk that he didn’t demand the numbers for, pouncing on the “weak details,” asserts Ms. Randolph. She uses data herself to highlight the strength of Mr. Bloomberg’s policies. However, too often she gets bogged down in statistics, which left me longing to return to reading the quick-start manual on my new digital alarm.

Do we really need to know that New York has 8,000 miles of streets, 12,750 miles of sidewalks, and more than 250,000 streetlights — for example — in a chapter that dissects the tragic 2003 crash of a Staten Island ferry into a maintenance pier, resulting in the loss of lives. The author’s point, apparently, is that things can easily go wrong in a city with an infrastructure as vast and as complicated as New York’s. Indeed, things can easily go wrong anywhere, and extraneous details don’t provide clarity. I would have been more interested in the private thoughts of Iris Weinshall, the transportation commissioner, whom Mr. Bloomberg advised to go home and “have a stiff Scotch” before tackling the crisis head-on in the morning.

Still, in these complicated times, it is refreshing to read about a politician who truly aims to serve public interest, even one who out of expedience converted from Democrat to Republican to Independent and back. Or whose arrogance led him to flout term limits in order to get elected a third time. New York had lower crime rates, a balanced budget, consolidated emergency services, 311, improved public health, 800 acres of parkland, the High Line, the 9/11 memorial, a green agenda, higher teacher pay, gay marriage, and a digital platform thanks to Mr. Bloomberg’s “dozen years as mayor, or 4,380 days, counting weekends and holidays.” If he has his way, we could look forward to an active presidency in 2021.

I didn’t remember — or perhaps never knew — how quotable he is. In fact, within the pages of “The Many Lives of Michael Bloomberg” there are enough gems to repackage into a collection of the former mayor’s wit and wisdom. “I was the kind of student who made the top half of the class possible” has inspired countless school groups. “Happiness can’t buy money” is an interesting twist — and true, if somewhat dispiriting. “It takes a special type of cowardice for elected officials to refuse to stand up and vote their conscience” is certainly one for our times.

Then there is the hilariously raunchy Bloomberg. As a C.E.O., he made a point of personally meeting new staff members, stopping unannounced to chat at their desks in the open space where everyone worked. In a conversation with a recent hire, a taciturn youth, Mr. Bloomberg asked him where he had gone to college.

“Brown,” said the young man, too nervous to elaborate.

“Ah, Brown,” replied Mr. Bloomberg, mistily recollecting. “That’s where I got my first blow job.”

The young man froze, stumped for a response.

“In Providence?” he finally said. The staff roared.

Thereafter, any off-color remark was greeted within the Bloomberg camp with “in Providence?”

But these are the bright spots. In the end, “The Many Lives of Michael Bloomberg” adds up to too few original insights that might cut New York’s larger-than-life mayor down to size. Without penetrating interviews with the subject and those who surround him, Ms. Randolph’s treatment comes off as somewhat distant and dry — though, ironically, it’s a take on Mr. Bloomberg that the data-driven mayor might appreciate himself.

Ellen T. White, former managing editor at the New York Public Library, is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” a book about great romantic women in history. She lives in Springs.

Michael Bloomberg lives part of the year in Tuckahoe.