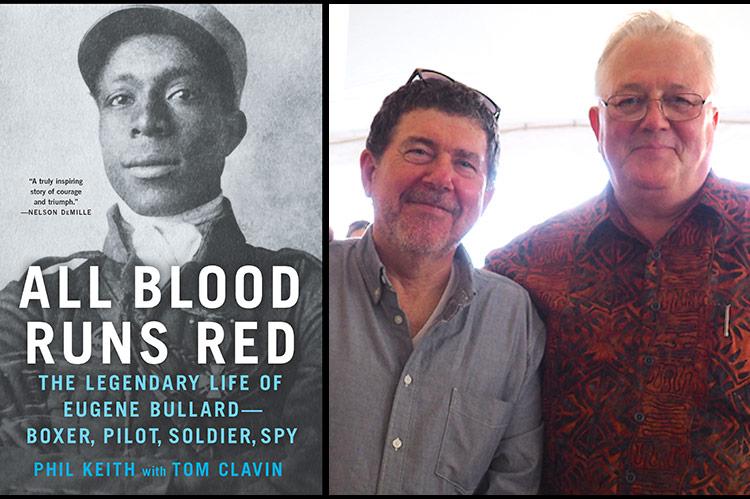

“All Blood Runs Red”

Phil Keith with Tom Clavin

Hanover Square Press, $27.99

On the surface, “All Blood Runs Red” by Phil Keith and Tom Clavin is a heroic story, an uplifting portrait of a unique individual, and an engaging account of a glamorous age framed by the two world wars. But between the lines runs an ugly undercurrent — suggested by the title — which adds to its impact.

Eugene Bullard was, some would say, a lucky guy. Born to an African-American father and Native American mother in the American South at the close of the 19th century, he ran away to find his fortune when still a boy and headed north, charming his way into hospitality with gypsy horse traders and work in a livery business, and jockeying his boss’s steeds to victory. He had ambition and wanderlust and a determination to end up in Paris.

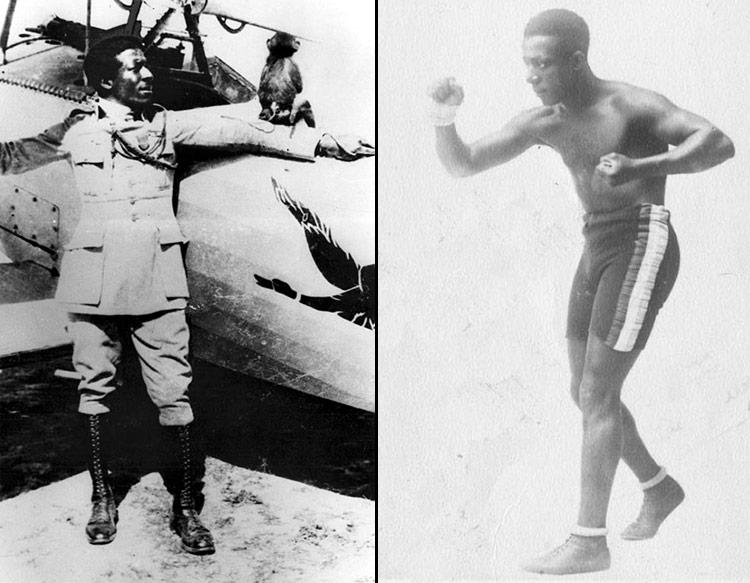

He got there in the end, as a stowaway of course, but via Britain, where he became a boxer and a vaudevillian traveling across Europe. Successful in both these pursuits, he finally made it to Paris in the fateful spring of 1914. By August, France was at war with Germany.

He volunteered for the Foreign Legion, saw action, earned military awards and decorations, including the Croix de Guerre at Verdun, and made important lifelong friends. He became a fighter pilot with the Lafayette Flying Corps, the group to which all American pilots in Europe belonged before the U.S. officially entered the war.

“He always flew with a large red heart painted on each side of his fuselage, right behind the cockpit. The heart bled, pierced by a dagger. Above the heart was stenciled the following: Tout Le Sang Qui Coule Est Rouge,” hence the title. (A note to the reader: In their quotation, the authors make one of several errors in French. In this case, they spell the French world for blood as sange instead of sang.)

By October of 1917 Bullard had flown 20 combat missions when he ran head-on into American racism. “The French were lucky to have him and the Americans would have been fortunate to have him as well . . . but they didn’t want him.”

“General Pershing’s staff convened an examining board to review potential pilots for transfer from the French escadrilles to the American Air Service,” and one of the four board members was a Californian, Dr. Edmund Gros, “a figure of great importance in aviation in the early days of the war, and an American who had powerful connections and an abiding prejudice against blacks. . . . Eugene Bullard truly was a hero of France. . . . Even so, Dr. Gros wanted him removed from the air completely. . . .” (The U.S. military was not desegregated until 1948 by order of President Truman.)

The war over, Bullard settled in Montmartre, “the epicenter of the cultural revival of postwar France . . . les années follies” (the authors mean folles). He became a drummer and opened a series of “bottle clubs” that featured American jazz.

At first his color was a mark of authenticity to Europeans, but then “the popularity of the postwar Paris art, music, and cultural scene attracted hundreds of thousands more Americans [who] brought their American-born prejudices with them.” Ugly incidents took place but were not tolerated by French authorities.

“It was a heady time for Eugene Bullard, grand impresario of a nightclub he had brought to life with his own hard work and gusty determination.” His customers included Nancy Cunard, Anita Loos, Charlie Chaplin, Cole Porter, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, Gloria Swanson, and the Duke of Windsor. Luminary musicians performed there: Mabel Mercer, Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, and a redhead singer known as Bricktop.

When war with Germany loomed once again, Bullard, by now multilingual, signed up with the spy agency known as Le Deuxième Bureau — for which he would be honored by the French government — to keep an eye on German Nazis living in Paris. In his club, intriguing “Casablanca”-like episodes transpired. Eventually, like Ilsa and her husband in the iconic movie, he had to make his way to Lisbon to find a ship sailing for America. He had a hatful of francs, which with the German occupation of France had become worthless by the time he reached America.

Disembarking in New York, he discovered he was the only veteran not to be offered support, the only black veteran stepping off the S.S. Manhattan that day.

Eugene Bullard died in 1961 at age 66. I won’t spoil the reader’s discovery of his last years by outlining them here. There are surprises, both sad and gratifying, but never to the credit of his fellow citizens. The man was extraordinary, really. This is a good read.

Ana Daniel, a graduate of Stony Brook Southampton’s M.F.A. program, is retired from business and teaching. She lives in Bridgehampton.

Phil Keith is the author of “Stay the Rising Sun,” among other books of history. He lives in Southampton. Tom Clavin’s previous was “Wild Bill.” He lives in Sag Harbor, which is where the two will read from “All Blood Runs Red” at the Eastville Community Historical Society on Dec. 21 at 2 p.m.