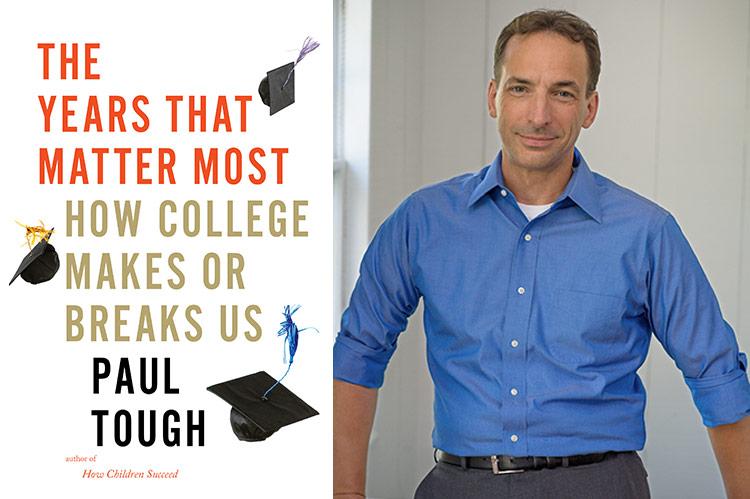

Paul Tough

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $28

Despite being a child of middle-class privilege, I was woefully unprepared that fall of 1961 when I joined my older brother at Harvard College. Like others of their generation, my parents’ commitment to education reflected a centuries-old Jewish tradition. Thankful and guilty for surviving the Holocaust in America, to say nothing of the Great Depression, they were determined that we should not squander the opportunities open to us.

Philip Roth captures this complicated mandate to “make something of yourself” in “American Pastoral.” We were to acquire a profession that would ensure financial success, along with portable knowledge should anti-Semitism force us to become immigrants, all while making a contribution to the larger social good.

For me, this mandate proved too heavy a burden, in part because coming from a small progressive school I was unused to being a little fish in a big pond, and in part because I wanted to make of myself not a doctor or lawyer but something not yet named, a gay man. Without a syllabus to guide me, I created my own curriculum by seeking peers and elders who lived in the after-hours world of places like Cambridge.

I was pleased to find that Paul Tough’s thoughtful and extensively researched book helped me better understand my own college experience as well as the experiences of many of today’s youth.

The big story that Mr. Tough tells is about the failure of higher education in the 21st century to provide equal opportunity to all segments of American society. Notwithstanding individual exceptions, he details how the current system systematically functions to benefit those who need it least, the rich and middle class, while promoting failure for the poor and racial minorities. Mr. Tough argues that everyone needs a college education to survive in today’s economy. But excessive reliance on unreliable tests, a lack of effective high school counseling, and the paucity of financial resources all work against marginalized students gaining admittance.

The exceptional outsiders to the system who manage to find a place in competitive universities are often academically and socially unprepared to take advantage of their success. For some, this predicament reflects the challenge of living between two starkly different worlds and finding a home in a landscape that has been shaped by privilege and unfamiliar accumulations of cultural capital.

Mr. Tough structures his narrative and sustains our interest through a series of interlocking chapters, each of which takes on a different aspect of the college conundrum. We are taken inside the test prep industry — attempts to rewrite the tests and initiatives to abandon them completely. At the same time we learn about the growing disparity in financing between elite and other institutions, the inadequate counseling provided to students in low-performing schools, and the lack of resources that place four-year institutions out of reach for so many.

In the hands of a less skillful writer, this story might lend itself to an overload of statistics, complicated graphs, and sociological jargon. Instead, Mr. Tough organizes each of his chapters around compelling stories of two or three students. He has an unfailing instinct for knowing when to move back and forth within each chapter between the personal sagas he relates and critical analysis of the problem under discussion.

We meet KiKi Gilbert, a gifted African-American student who surmounts the challenge of living in seven states and attending 10 different elementary schools to earn a place at Princeton, only to find that lacking the cultural capital acquired by her more privileged classmates earlier in life, she could not fit in.

By contrast, Kim Henning, a successful high school student from a struggling family in Appalachia, chose a local college over an elite university in order to be close to home. Although she ultimately achieves success at the local college, Mr. Tough is quick to remind us of the opportunities she missed by not attending the more competitive one.

Most of the students Mr. Tough profiles come from far less privileged backgrounds than I did, but I resonated with the experiences of the young high-achievers who arrive at elite institutions only to lose all confidence in their abilities. No longer at the top of the academic food chain, surrounded by students who appear more able, a core part of their identity is thrown into question.

I was intrigued that Mr. Tough not only tells his story through the lives of individual students and families but also through the lives of people who are striving to change the system. We are introduced to Uri Treisman, a professor at the University of Texas who has transformed math teaching to accommodate students from diverse backgrounds; Angel Perez, who has designed more equitable admissions practices at Trinity College; Father Stephen Katsouros at Chicago’s Arrupe College, who has created robust supports for poor, urban youth experiencing a panoply of home-based problems.

In the progressive tradition in which I grew up and later taught, we talked about attending to the needs of the “whole child.” Reading about these innovative programs, including multiyear supports that address the complex socio-emotional as well as academic needs of young students growing up in stressful circumstances, reminded me that students of all ages need to be treated as complex human beings. A final year or two of high school guidance or a freshman-year seminar are inadequate substitutes for the sustained work that is required by students who have been ill prepared to meet the challenges of contemporary college life. Who will pay for such costly programs?

In the final chapter, Mr. Tough suggests that American conversations about higher education have shifted dramatically over the last hundred years. Policy debates once conducted in terms of the economic and labor force benefits of higher education are now lodged in language of ideology and identity, with some politicians framing college as cultural signifier separating “us” from “them.” Where once college was understood as a social good, something that benefited society as a whole, in the neo-liberal state it is now identified primarily as an individual good.

In a culture where the individual takes precedence over the collective, systemic inequities in distribution of educational resources among rich and poor, black and white, are masked. I only wish that Mr. Tough had spent more time unpacking how this shift has become embedded in our thinking and how it might be undone. Because as we learn every day in every way, we cannot rely on those in power to act in the civic self-interest.

Jonathan Silin is a resident of Amagansett and Toronto and the author of “Early Childhood, Aging, and the Life Cycle: Mapping Common Ground.” He’s online at JonathanSilin.com.

Paul Tough lives part time in Montauk.