“For Now”

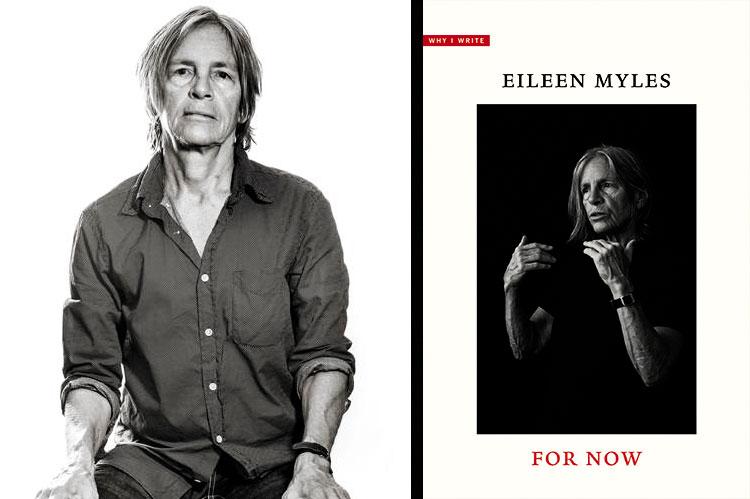

Eileen Myles

Yale University Press, $18

Among Eileen Myles's many contributions to American letters is a confidence that poetry can function as a transparent window into an otherwise invisible inner life, that the boundaries between reader and writer are porous, that we actually can get to know each other. It's a confidence in our powers of empathy and imagination. That, or it's confidence in the illusion of such intimacy.

Reading Myles's poems feels a little bit transgressive, like eavesdropping on the next booth at the diner, or sorting through someone else's trash and finding scribbles on the backs of their junk mail envelopes and grocery store receipts. The poems, typically in short, irregular lines of breezy vernacular language, feel dashed off, effortless, and deceptively easy to write. Instead of Keats's "wreathed trellis of a working brain," Myles gives us something messier, its detritus, maybe. Here's one called "Writing":

I can

connect

any two

things

that's

god

teeny piece

of bandaid

little folded

piece

of bandaid

I ran

to the

bathroom

to see

my face

sometimes

I don't

want to

see my

face in

the mirror

sometimes

I can't

bear

my thoughts

sometimes

I can't

do anything

but that's

okay

bandaid

book

god

that's

right

That interior mess, where "bandaid / book / god" are jumbled together almost on a dare, since "I can / connect / any two / things," is what Myles takes on in "For Now," a book-length essay in Yale's "Why I Write" series. The essay, like "Writing," enacts the very strategies it identifies as essential to its author's poetics. For example, it chronicles its own construction, so that, as we read it, we learn not only why Myles writes, but also how this particular, unique piece of writing came to be.

First given as a talk, "For Now" skips around geographically to the abodes where it was written, primarily Myles's rent-stabilized apartment in New York City and an outbuilding at their home in Marfa, Tex. (Myles uses the they/their pronoun), though the essay also visits a number of other locations, including a house during a stint in San Diego, and, briefly, the East End. A milk crate full of manuscripts travels like Myles between them. These externalities loosely mirror or correspond with Myles's internalities (their love life, their financial shape, their state of mind, frankly narrated in what sometimes amounts to an invasion of their own privacy), the one constant, like the milk crate, being writing itself.

Time is another messy concept in this essay. The Eileen Myles at the beginning of "For Now" is not the same Eileen Myles at the end. We learn that the essay was constructed over a series of "nows" that began long before publication. First, they'd gotten the wrong date for giving their talk, and so they started it, a year too early, in New York, then revisited it here and there, between court dates with a landlord, renovations in Marfa, flashes back to a childhood in Massachusetts, efforts to sell their archives to a university, early New York publishing successes, their circle of friends, and musings on past lovers.

Like "bandaid / book / god," in the poem, these time locations tend to fuse. For example, in thinking about their past lovers while imagining their archives in some future use, Myles tells us "what researchers really want to know is who the poet fucked, or what the poet fucked, probably how they fucked. And you know honestly it's one of the main things I write about in my notebooks."

Is that why Eileen Myles writes? To sate the curiosity of readers to come? At other points in the essay, they compare writing to riding a bike, to inventing puppet shows, and to copying, in the way that one illuminated manuscript is a copy of another. In Myles's case, the copy is the poem, turning what's inside the poet into something outside on the page, where others can see it, so that it's suddenly two places at once: with us, the readers, and, as source material, still within the poet.

But Myles also compares their writing instinct to an alibi, the defense against arrest, which connotes the opposite: alibis get you off the hook because you can't be two places at once. The motives, like Myles's past girlfriends, have irreconcilable differences, to which I can almost hear Myles replying, "that's / right."

This messy dualism is externalized in the prose style as well, sentences with loosely connected clauses, sometimes punctuated, sometimes not, that don't really begin and end so much as they veer within earshot, then wobble off: ". . . slowly in my twenties and with a deepening of conviction since then I discovered that to be real was an interior project. The actions you felt inside, the stabs and constant pedaling, practiced and eventually moving out into the world like this thing that I'm writing are the eventual visible practice and it sounds like me and it looks like me changing shape for a very long time and then voila a book."

Voila. Myles makes it sound easy, until you stop and think. Myles is after an elusive individuality that "looks like me" but also is "changing shape." Moreover, to have a "visible practice" takes consistent, long-term effort. The milk crate doesn't lug itself. Myles's transparency, that movement from "interior project" to "out into the world," might well be an illusion, but, at least for now, it's an illusion available in hardcover for $18.

Julie Sheehan is the author of the poetry collections "Orient Point" and "Bar Book." The director of the B.F.A. program in creative writing at Stony Brook University, she lives in East Quogue.

Eileen Myles is a regular visitor to East Hampton and has family here.