“Horse Crazy”

Sarah Maslin Nir

Simon & Schuster, $28

There could be no better title for this memoir, as it encapsulates everything about Sarah Maslin Nir. After all, love does make you crazy.

Ms. Nir's "Horse Crazy," released on Aug. 4, is not a single-minded tale of horses but a cleverly blended encyclopedia rich with reportage and intimate storytelling. If you are expecting something purely horse-centric, look elsewhere. This thoughtful memoir covers a lot of territory, from combating loneliness to navigating grief and, well, okay, horses.

Ms. Nir grew up on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and spent summers in East Hampton, where her parents bought a 900-square-foot house in Springs in the 1980s. Early in her career, before she wound up at The New York Times, she was a writer for The East Hampton Star. She refers to that experience throughout the memoir, and to the South Fork, too, the site of some of her fondest and most painful memories.

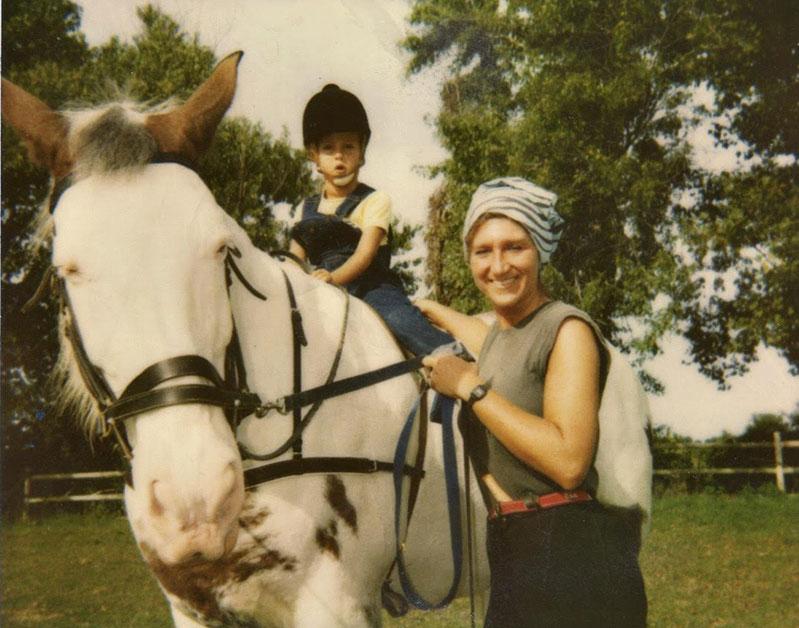

Each chapter is named after a different horse in her life. She begins with the first one she ever fell off. His name was Guernsey. The pair met when the author was only 2 years old, when her parents "schlepped" her off to a barn off Old Stone Highway. Mid-trot, Guernsey flung her tiny body from his mammoth back and nearly trampled her. Some years later, she discovered that Guernsey's obituary ran in a 1995 issue of The Star.

"Putting me on a moving horse would be the secret to getting me to sit still," Ms. Nir writes. "They had no idea what their clever plan would set in motion."

Behind her unshakable nature were the fierce women who raised her. Her maternal grandmother gave birth to triplets, who then died just hours after their delivery. She went on to adopt two newborns, Ms. Nir's uncle and mother, who, although cut from a different biological cloth, developed the same intensity for life.

The youngest of four and the only one with a different mother, Sarah felt isolated from her three half brothers, the oldest of whom was 20 when she came into the picture. She spent many days alone in her bedroom playing with plastic horse figurines.

By the time she was born, her father was too old to entertain a child. He and her mother, who was about half his age, both psychologists, were usually too absorbed in their work to pay much attention to her. "I pined for parents who had little time for someone as yet too young to make cocktail conversation."

Ms. Nir writes of being tormented by the distance between her and her father and three brothers. She doesn't blame her father for his aloof disposition. He was a Holocaust survivor and grief-stricken because of it. "So crisply is trauma transmitted through generations," his daughter says.

Similarly, she attributes her brothers' distance toward her to her untimely birth. "The truth is that to them, I was an invader, my existence imbued with the heartbreak of their own family that fell apart. The story I entered into was already written. I didn't even lift a pen."

She learned to navigate the complexities of growing up, whether emotional abandonment, intellectual curiosity, or familial trauma, through the horses in her life. For Ms. Nir, horses are not merely animals but majestic steeds capable of offering emotional companionship. They serve as counterparts. In many ways, they are human to her. Their hooves grow like fingernails, they daydream, and they even like to get high.

Admittedly, you might get lost in equestrian jargon at times, but she pulls you back in with the ease and poignancy of her stories.

Like me, Ms. Nir is a Jewish girl from the city, born to an immigrant father. We both would frequently sneak out as teenagers, which in her case involved an expertly executed plan of tip-toeing past her trusted doorman and then hailing a yellow taxi that would take her into the never-sleeping city. "The night was a new thing to us all," she writes of her high school years.

Yet she admits that the thrill of wild nights out expired quickly. She recalls walking onto strobe-light-pounding dance floors as a teenager with the arms of promoters at her waist. She somehow became even more of a night owl when she got a gig at The Times as the "Nocturnalist," which meant she worked the graveyard shift frolicking in the city and reporting on it for a nightlife column.

But Ms. Nir also found fulfillment in learning about horses, feeding the beast that is her intellectual curiosity at stables in East Hampton, on the concrete paths of Central Park, and in the hallways of the American Museum of Natural History.

"Only one animal has such an extensive collection devoted to it, in fact the largest anywhere in the world," she says of the museum. "The existence of this upstairs warehouse of thousands of horses had been unknown to me. It is reserved for scientists, not horse-mad little girls and their nannies." She recalls how as a young girl she would trot through the galleries in the upper recesses of the museum, gawking at displays of horses' hock joints and preserved eye sockets.

Later in the book, she reckons with a memory of watching a trainer abuse her beloved horse, Willow, as a way to "force the crookedness out of her. I watched at the fence line as Willow was whipped in pinwheels, the bit cranked so that the horse's head almost touched the woman's thigh. For the next forty-five minutes, the mare was spun in circles until sweat foamed on Willow's neck and the lather slid down to her hooves."

"Sometimes I can't sleep thinking about how I followed orders to remove the water buckets from the show horses' stalls the night before a horse show so they would be 'quiet' and subdued on competition day." It took her eight years, but eventually she never went back to those stables.

She concludes with a chapter, "Tango," about the time she went fox hunting with an old friend in the snow-packed woods of North Salem, N.Y. After her father died, Ms. Nir engraved his last name onto the cantle of her saddle.

"It was silent, but I heard the roar of history and time, of belonging and not belonging, vibrating the air. Here in this closed-off world, an outsider had led the hunt and a Holocaust survivor had ridden alongside her, perched on the back of my saddle."