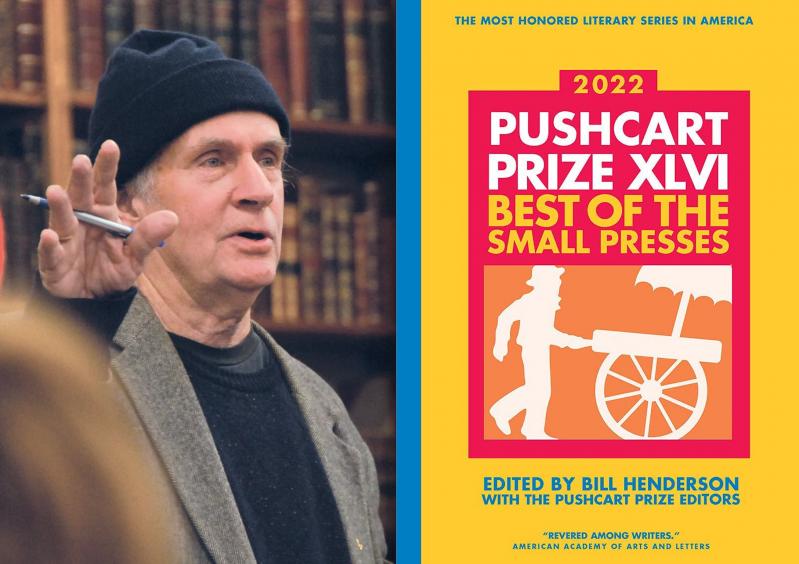

“Pushcart Prize XLVI”

Bill Henderson, Editor

Pushcart Press, $19.95

Every year, for 46 years running, the Pushcart Prize, under its indefatigable editor, Bill Henderson, culls a selection of poetry, fiction, and essay from thousands of nominees and publishes an anthology. The nominations come from Mr. Henderson's network of contributing editors and from the hundreds of literary magazines and small presses publishing in the U.S. and across the globe.

We don't deserve such riches, but here they are. As Mr. Henderson writes in his introduction to this year's edition, "Never before, in the estimate of this rather seasoned observer, has our literary world been in better shape."

The 2022 Pushcart anthology is, above all else, timely. Not only do its contributors represent the wide spectrum of voices getting published today, but their contributions survey the abuses specific to our moment — racism, sexism, homophobia, climate catastrophe, and political violence. In them, a dazzling range of characters suffer, fight, fail, and occasionally triumph against forces arrayed with particular ferocity against the powerless. Literature explores this theme better than anything, so the anthology brims with writing of exceptional quality. It's a gift for readers eager to imagine other people, what it's like to wear their skin, to walk in their shoes.

In other words, this year the Pushcart Prize goes to the woke. I use that word to mean alertness to individual differences, recognition of social inequalities, and confidence that empathy and imagination can bridge those differences to ameliorate inequalities. Our thoughts now on this word "woke" are muddy, even, dare I say, intentionally polarized. Is wokeness a form of virtue-signaling or virtue itself? A liberal attack on free speech or a voice for the voiceless? A sneaky blue-state plot to make white people or men or heterosexuals feel so bad about themselves that they have to go out and shoot a prayer group or nail technician or patron at a nightclub? Is it a synonym for "politically correct" or "kind"? For the iron hand of the state? For left-wing propaganda forced down the throats of parents in Loudoun County, Virginia?

In our national conversation, the fact that we have no common definition of "woke" barely matters, for a new term will take its place soon enough and we will continue our argument then. But as readers, wokeness is a good shorthand for the kind of engagement with difference that happens to us when we read, especially when those characters and sensibilities we fall in love with on the page come up against a hostile social context. The Pushcart anthology highlights exactly that form of conflict.

Start at the beginning, because these selections are thoughtfully ordered. First comes a short story that withholds the pronouns for its main character until midway through, forcing readers to confront any gender assumptions they made. It's followed by a poem whose title, "Every Poem Is My Most Asian Poem," does not mislead. The anthology then cycles through an essay on gun culture, short stories on class warfare and toxic masculinity, a feminist fable, and a story about a gay kid growing up in the Midwest. Three hundred and fifty more pages await.

One delight of the Pushcart is to discover unknown writers, who are published right alongside established ones. This edition follows the distinguished poet B.H. Fairchild with Senaa Ahmad, who has yet to publish a book and who writes high-end science fiction. She is the author of that feminist fable mentioned above. In it, Anne Boleyn is murdered again and again by Henry VIII, only to return to life, as centuries pass and we are left to ponder the curious durability of women trapped in loveless marriages.

Ms. Ahmad is by no means the only writer of dystopian fiction: Lara Markstein, Michael Kardos, Olivia Clare, and others contribute dystopias set in such wreckage-prone locales as shopping malls and acting schools. In an anthology concerned with our current toxicities, it makes sense. Dystopias are very good at allegorizing social forces like sexism, something that young-adult writers have known for a long time. As the boundary between Y.A. and literary fiction blurs, more and more writing crosses genre boundaries. For example, the noted journalist Jabari Asim, who also writes books for children, contributes a poem.

There's also plenty of realism in the pages of the Pushcart, notably "The Loss of Heaven" by Dantiel W. Moniz, first published in The Paris Review. She crafts a sensitive portrait of an aging, blue-collar Black man whose wife is dying of cancer and whose grief leaves him horribly vulnerable to violence. Several other short stories are set in middle and high schools, where weird things happen, giving them a sci-fi feel despite their realism.

The nonfiction selections tend toward the ecological: salmon fishing in a changing climate with Cathryn Klusmeier ("Gutted"); Rebecca Cadenhead, a Harvard-bound student and the only Black girl in a group of gap-year kids, slaughtering a lamb in Patagonia in her study of class and privilege ("My First Blood"); Lea Purpura in "The Creatures of the World Have Not Been Chastened," looking, as only she can look, at a dead deer; another study of class and Covid-19, but through the eyes of a single mom (Jennifer Bowen Hicks) looking at cows. The social context is never far from these pastoral scenes.

In other essays and poems, Black Lives Matter makes several appearances, as do #MeToo, dating apps, gentrification, anticolonialism, the pandemic, and household pets, whether here in the U.S. or in Yemen (Threa Almontaser's brilliant poem "Muslim With Dog").

Given the care for the order in which the Pushcart selections appear, there's a lot of pressure on that last spot. How do you end such a comprehensive survey of social ills and the unique individuals who experience them? Leora Smith rises to the task with her essay "The God Phone." Set at the Burning Man festival over a number of years, it documents a recurring art installation, a phone booth set up at the site for talking to God. Any participant can pick up the phone and God will answer. Who's on the other end? Other Burning Man participants. The phone line leads to a "secret location" that festival-goers quickly find and then staff.

Of course, none of these volunteer Gods have any particular qualifications to handle the calls that come in, which range from silly banter to serious questions one would assume are better directed to suicide hotlines. Except the essay reveals how essential the connection between one ordinary person and another is. God is right there in other human beings — beings who may not look like you, share your experiences, or suffer the same socially inflicted indignities, but who, like readers of literature, can imagine across those differences. They are beings who, like readers of this anthology, will find deep pleasure and urgent relief in the awakening that each point of contact with another brings.

Julie Sheehan is the director of the B.F.A. program in creative writing at Stony Brook University. She lives in East Quogue.

Bill Henderson lives in Springs.